Person: Suhair Khan

My person is Suhair Khan, project manager at Google Arts & Culture. A click on the link will immediately pull up the world’s array of art collections, stories, and cultural sites onto your screen. You can check out the local Guggenheim Museum to see what exhibitions are happening or hop over to Vienna to see your favorite painting of ‘The Kiss.’ If you’re feeling adventurous, you can use one of Google’s VR tools to stroll down the murky paths of the Catacombs of San Gennaro in Naples and discover a new collection of mosaics. The beauty of this platform is everything is up to the viewer to decide where they want to go, what they would like to see, and how long they want to be there for. And the best part? This viewing experience is free and meant to be enjoyed in the comfort of one’s home (or in my case, a tiny coffee shop in Greenwich Village).

So what is Google Art and Culture? Simply put, it is a platform launched in 2011 to “provide access to art and culture to everyone and everywhere” (Gajardo & Lau, 2017). Google Art and Culture has kept this mission true. So far, Suhair and her team of engineers have partnered with over 1200 non-profit cultural institutions, galleries, and artists across 70 countries to share, preserve, and present some of the most beautiful artworks and curated stories online.

Suhair is no stranger to multicultural experiences. She grew up in Milan, London, and South Asia and have led projects in the UK, Australia, Indonesia, and Korea. Her mission is to have art and culture accessible to people who can’t travel and “make sure distance and culture doesn’t get in the way of resources and sharing” (Appleby, 2018). This is what technology has allowed us to do: break down the barriers and show art no longer needs to be confined to a physical space but can be made accessible anywhere online. Suhair is reconstructing the way people engage with art by making the experience easier and less intimidating. Instead of traveling to a particular place, the artwork is brought to the viewer. This reminds me of the ‘armchair traveler’ when early photographers would send souvenir photo albums to loved ones back home so they can feel like they were visiting these faraway places without leaving their seat. Technology has allowed us to revitalize the role of a digital ‘armchair traveler’ by making the experiences even more realistic and interactive.

So how can we relate Suhair’s work to the information field? First, Google Art and Culture is showing us a way we can present digitized information meaningfully by “creating networks of connections with context” (Appleby, 2018). We can see this with museum curators’ taking the role of digital storytellers as they now need to consider writing stories for audiences outside of the typical museum-goer realm. Second, we can take note of Google Art and Culture’s broad ways of searching for information. Categorizing artworks by color, popular topics, place, time, historical movement, etc., can inspire us to think outside of our usual groupings and be more ambitious in the pathways we create. Third, a look into Google’s features such as shared birthdays or their famous art selfie app that matches viewer’s face with an artwork provides more intimate and personal ways of engagement that IXD professionals can consider. Finally, the biggest takeaway is the multidisciplinary approach to sharing information. By collaborating with institutions and including tools that compare artworks from various cultures, the information no longer exists as a single narrative in support of one view but is transformed into a collection of narratives in support of cultures around the world. Thereby, viewers are able to get a well-rounded understanding of society and adopt a different cultural perspective.

Place: The Street Museum of Art

I decided to take a more unusual and unconventional route by picking The Street Museum of Art (SMoA) as my place of interest. I would say this is unusual than the rest because SMoA isn’t actually a physical museum, but it is an international, public art project that takes their exhibitions onto the streets and uses the city’s urban environment as their canvas. So far, the exhibitions have been held in New York, London, and Montreal. A look on SMoA’s website reveals their projects have transformed city streets into gallery walls where “admission is always free and the hours are limitless” (“The Street Museum of Art”, n.d.).

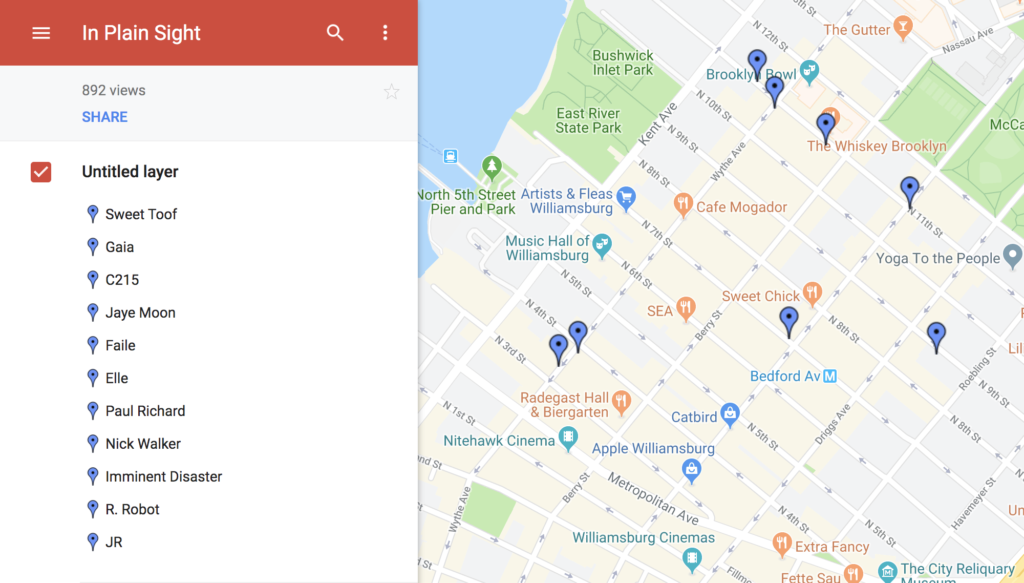

‘In Plain Sight’ is an exhibition held in Williamsburg, Brooklyn and features the works of eleven artists “to encourage visitors to rediscovery this city through a street artist’s perspective…. And imagine the artists on their search for the ideal urban canvas” (“In Plain Sight,” n.d.). As mentioned, most of the artworks are hidden or have been cleverly positioned so the viewer would pay attention to sites that are usually ignored and thereby, ‘rediscover’ the urban city. This won’t apply to me as much as I have never been to Williamsburg before. With nothing but a digital Google map, I took the subway to Williamsburg on a sunny Friday afternoon to embark on my urban scavenger hunt.

While searching for these artworks, it made me think about some of the topics discussed in class, such as the concepts of permeability and permanence. What happens when these places don’t exist anymore, will the artworks still be archived? How will it be archived – through photographs snapped and shared? I was only able to find two out of eight artworks and gave up on the last three. It may have been partly my fault, as I chose to go with the exhibition from 2012. However, this exhibition made me also think about the art world- how does this experience differ from an exhibition at a museum or gallery setting? In my opinion, the biggest difference was that this urban museum experience became much more personalized. I wasn’t confined to a physical space, I didn’t feel intimidated, and I loved how customizable the guide was. I could listen to music, pause the exhibition and grab a bite to eat, or even complete it over a span of a few weeks. It was also nice to know that my exhibition journey is unique in the sense that there was no specific path given to see the artworks, while museum settings usually give viewers a direct path to follow.

Photo: Janet Liu 2019

This exhibition also varies greatly from the online ‘In Plain Sight’ on Google Art and Culture. Instead of having everything presented at once on a single platform, SMoA was completely opposite: I had to physically go out and search for all these places myself. Unlike the ‘armchair traveler’ experience that Google Art and Culture provides, SMoA builds upon the ‘in situ’ concept of experiencing the art at its original place. Even though most of the artworks are no longer on view, I would say art in situ becomes more of a valuable experience because I had to physically travel and search for the places. Not knowing what to expect, then being incredibly amazed to find the artwork became a much more memorable, emotional, and personal experience than it would have been seeing it as a digital exhibition.

Thing: Little Robot Friends

I chose the Little Robot Friends (LRF) for my thing. I was searching for fun gift ideas for my nephew when these little tiny adorable creatures caught my attention. Hours later, I found myself still watching their YouTube videos and I ended up almost buying a robot myself.

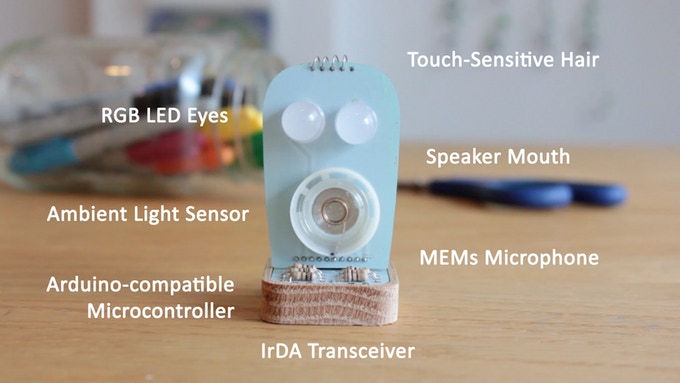

LRF are programmable, customizable robots that teach kids aged seven or higher how to code. For $49.99, you can purchase a DIY kit or already assembled kit, which also comes with its own coding software filled with open-source-code to program new robot behaviors.

“They can sense the amount of light in a room, they can hear with a small integrated microphone, they can detect your touch and they can also communicate with other Little Robot Friends using infrared light (like your TV remote). They have two RGB LED eyes and a 250mW speaker for expressing their current mood. The brain is an 8-bit 32K microcontroller that provides a lot of space for coding behaviours and storing memories.”

(“Little Robot Friends,” 2016)

This project is similar to Google Art and Culture and SMoA because of the flexibility of customization for its users. For instance, you are welcome to alter LRF’s personality. I would say LRF is able to create an even more engaging experience than the rest because of the emotional connect. They are robots that are personalized, tangible, meant to be held in one’s hand that can elicit empathy with the robots, and empathy with coding.

“Each interaction with your Little Robot Friend is stored as a memory, and changes how it will behave over time. We are working hard to make this a profound experience, one that can surprise you and make you smile as you watch your Friend grow up.”

(“Little Robot Friends,” 2016)

This makes me think of our previous discussions of provenance, and the idea of treating archives as objects. If we are able to adopt this view and see archives as tangible, living objects such as the little robot friends, then perhaps we will be more mindful and remember that our interaction with the objects will also affect its context and memory.

References:

Appleby, E. (Producer). (2018, May 03). Episode 33: The Art of Connectivity: Suhair Khan from Google Arts & Culture. [Audio podcast]. Retrieved from http://sotapodcast.com/episodes/33

Gajardo, T., & Lau, Y. (2017). The Woman Who is Bringing Museums & Cultural Sites from All Over the World to your fingertips. The Artling. Retrieved from https://theartling.com/en/artzine/interview-head-google-arts-culture-suhair-khan/

In Plain Sight. (n.d.). The Street Museum of Art. Retrieved from http://www.streetmuseumofart.org/in-plain-sight-1

Little Robot Friends. (2016). Aesthetic Studio. Retrieved from https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/aesthetec/little-robot-friends

The Street Museum of art. (n.d.). The Street Museum of Art. Retrieved from http://www.streetmuseumofart.org/about