The word interference typically has negative connotations; in today’s capitalist landscape it can invoke the disruption of efficiency and streamlined workflow. In the context of activism, interference is necessary for dismantling oppressive structures. The Interference Archive in Brooklyn operates under this ethos: “to use the collection as a way of preserving and honoring histories and material culture that is often marginalized in mainstream institutions.” Their standards align with ML Caswell’s idea of archival representation—as posited in “’The Archive’ Is Not an Archives: On Acknowledging the Intellectual Contributions of Archival Studies”—as “an ongoing collaborative process that welcomes diverse input, not an end-product (such as a finding aid) that presents an authoritative or definitive voice” (Caswell, 10).

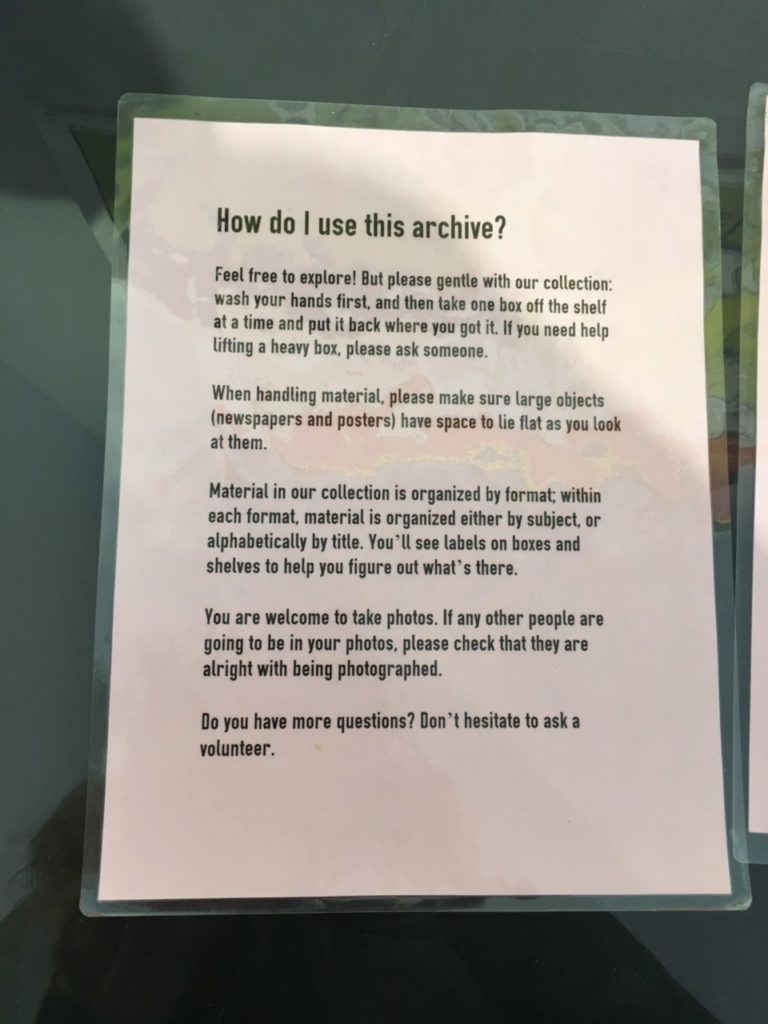

Founded in 2011, the archive is located in an unassuming gallery space at the intersection of Park Slope and Gowanus. It is an entirely open-access, open-stack archive, meaning that anyone from the public is free to enter during operating hours and browse the endless shelves of ephemera. For the easily distracted and endlessly curious like myself, the space is a dream. There are flat file shelves of posters, newspapers, stickers, buttons, and pamphlets from various activist movements, as well as a whole library of books and records in the back, and a shared work area with the independent publishing company Common Notions. The archive is open four days a week and is entirely volunteer run. Whoever is staffing at a given moment acts as a de-facto catalog, in addition to assisting in collection processing, stabilizing, and creating finding aids.

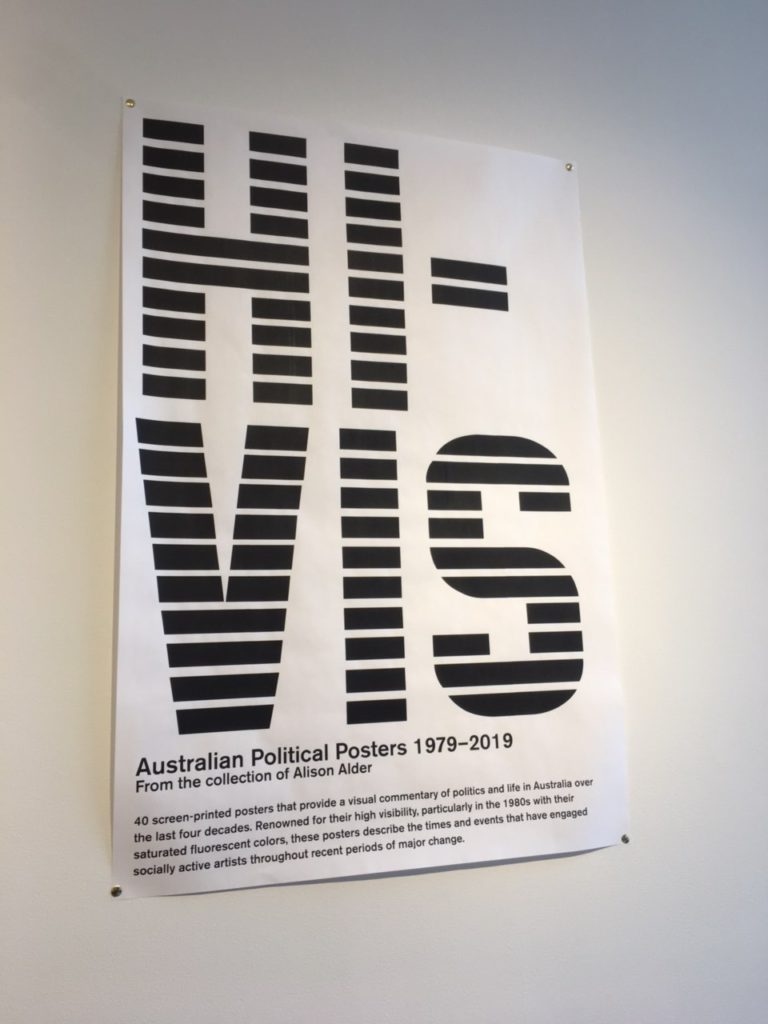

One of the first boxes that I browsed through contained records of anarchist infoshops from the Beehive Collective, an anarchist group located in Washington DC in the 1990s. In addition to their open stacks, the Interference Archive also curates exhibitions open to the public. A collection of Australian political posters from 1979 to 2019 is currently hanging in the front hall. The posters run the gamut of environmental activism campaigns to art festivals. The next exhibition, also posters, will be curated in partnership with The Poor People’s campaign, an organization for income equality founded by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

I had the fortune of being able to wander the Interference archive—no appointments are necessary—and speak to one of its founders, Kevin Caplicki. Kevin, whose background is actually in graphic design elaborated on the accessibility fostered by the archive. “Our collection policy is anything that’s produced in multiples, via grassroots social movements, that communicates their demands. The materials are international on scale and the idea is to provide a public space where all of these materials can be accessed by anybody because we, as a counter-institution, to engage with this material to understand radical history.” His description also brought to mind John Gehner’s hope for the future of libraries, “The promise of the social exclusion/social inclusion framework is that we don’t have to dwell on one particular aspect of a person or community—their income, age, gender, race, ability level—but simply on the fact that many people are forced to live on the margins and cannot participate in society as equals. Remedies are rarely immediate or easy, but libraries are well-equipped to do more and better” (Gehner, 45).

In the current political landscape, the archive serves as a space of dynamic conversation, where ephemera collected from past movements can enrich activism today. “We want these materials to inspire people to reproduce these kinds of resistance and organizing,” Kevin says. “Ideally, browsing the archive will inspire people to get organized now or create graphics now. Hopefully we can progress to a world that we want to live in.”

Kevin also elaborated on the manifold challenges that come with maintaining an entirely volunteer run community archive. For one thing, only a small portion of the archive is digitized just because resources for that equipment and manpower are limited (the archive is entirely donation based and community supported as well). “Labor and time are the biggest limitations. We do have monthly sustainers that donate that covers overhead costs.” As a horizontally run space, there are different groups that run different projects, but there is always a shortage of volunteers.

The archive often gets researchers, which Kevin says is a good excuse to figure out new points of access to the archive. The process of working with researchers usually starts by finding out what topics they are interested in, if they are interested in working with different formats. From there, the volunteer and researcher will just start pulling boxes and exploring.

“We try and find different new ways to create finding aids to guide people through the materials. As a staffer, I am here to go on the adventure of exploring the archive with visitors.”

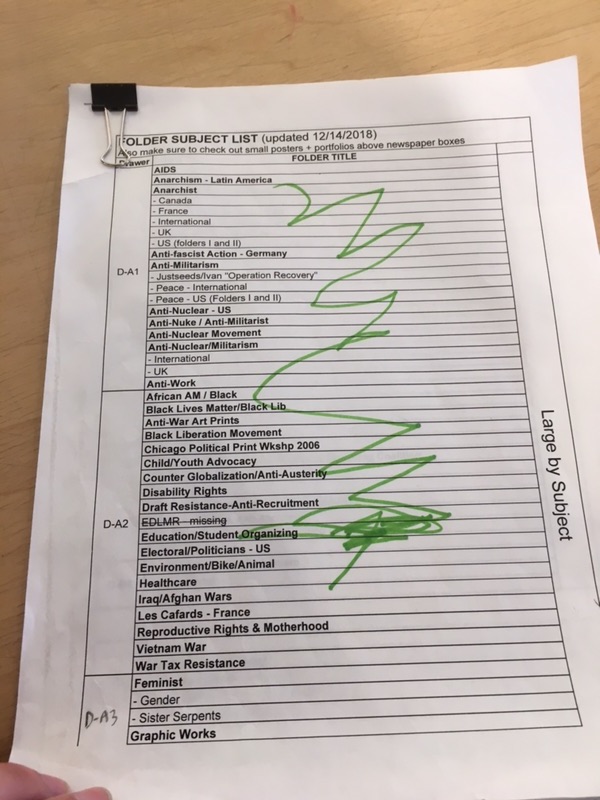

The space itself is meticulously organized. I was able to look through a finding aid of posters, organized in flat file cabinets in the back of the archive. “We want people to be able move from specific to general and vice versa whenever they need to,” Kevin says of the archive’s finding aids. On the poster finding aid, the posters are arranged into folders, which are listed by subject and geographic location. There are also finding aids for documents, stickers, and buttons.

The staff is a mixture of archivists, librarians, artists, activists, and others from the community. When I arrived, a group was in the process of stabilizing issues of the Globe from the 1960s. Some used gloves to handle the papers.

The space is truly dynamic: in addition to exhibitions, the archive also features film screenings, workshops, panel discussions, and can serve as a political organization space. As I left, I immediately began looking forward to when I could return again. The archive is always in need of volunteers and a simple email is all you need to get started. There are no library science or archive work prerequisites. In a neighborhood of rapid gentrification, the Interference Archive stands out as elevating the communities that have been overlooked in development.

Citations

Caswell, ML. “Archives on Fire: Artifacts & Works, Communities & Fields.” Reconstruction: Studies in Contemporary Culture, vol. 16, no. 1, 4 Aug. 2016, pp. 1–21.

Gehner, John. “Libraries, Low-Income People, and Social Exclusion.” Public

Library Quarterly, vol. 29, no. 1, 2010, pp 39-47.

By Sarah Goldfarb, Info 601-01 (Structured Observation Assignment)

The Fales Library and Special Collections, located on the third floor of ElmerHolmes Bobst Library at

The Fales Library and Special Collections, located on the third floor of ElmerHolmes Bobst Library at  phone-logs, to art-objects, this collection contains the primary source materials for the topic of the discussion today,

phone-logs, to art-objects, this collection contains the primary source materials for the topic of the discussion today,  archive-based exhibition, discuss his kindred relationship with Wojnarowicz. He conveyed a deep understanding of the symbols of Wojnarowicz’ art that in part had developed through years of studying the materials on display.

archive-based exhibition, discuss his kindred relationship with Wojnarowicz. He conveyed a deep understanding of the symbols of Wojnarowicz’ art that in part had developed through years of studying the materials on display. which may have been used in Wojnarowicz’ early photo series, Arthur Rimbaud in New York. Archival material represents a sizable portion of the work on display. To name a few examples, there is an audio recording of a 1992 reading given by Wojnarowicz at The Drawing Center; a black and white unfinished film that was borrowed from the Fales Collection; and a vitrine containing a pamphlet from the American Family Association and the annotated Affidavit for David Wojnarowicz v. American Family Association and Donald E. Wildmon.

which may have been used in Wojnarowicz’ early photo series, Arthur Rimbaud in New York. Archival material represents a sizable portion of the work on display. To name a few examples, there is an audio recording of a 1992 reading given by Wojnarowicz at The Drawing Center; a black and white unfinished film that was borrowed from the Fales Collection; and a vitrine containing a pamphlet from the American Family Association and the annotated Affidavit for David Wojnarowicz v. American Family Association and Donald E. Wildmon.