Anthony Clark describes presidential libraries a “fake history sites” and “propaganda machines.” (Hard to argue after visiting some.)

Archivists Round Table Symposium #archives pic.twitter.com/pJXCVBCG0K

— Geof Huth (@geofhuth) October 19, 2018

Would Donald Trump be president if presidential libraries were more honest about the political histories they represent? That was one of the thorny questions raised by Anthony Clark during his keynote address at the annual New York Archives Week Symposium presented by the Archivists Round Table. The theme of the day was “The Uncomfortable Archive,” and Clark, author of The Last Campaign: How Presidents Rewrite History, Run for Posterity & Enshrine Their Legacies, had a lot to say about the things that make him uncomfortable with the current state of presidential libraries and museums.

Clark has ample first-hand experience with these federally maintained institutions, which, though spurred into action by Franklin D. Roosevelt, weren’t formally established until the Presidential Libraries Act of 1955. Clark worked in the U.S. House of Representatives on a House Oversight Committee that investigated the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), and in 2003 began research on his book. After visiting the few presidential libraries that exist (13 as of today, with Barack Obama’s currently in controversial planning stages), he said he encountered a lot of things that made him uncomfortable. Noting that the presidential libraries account for a quarter of the federal archives budget while only holding five percent of its records, he expressed additional concern over the outside funding they receive. By ingratiating themselves to private funders, he said presidential libraries are doing “wholesale damage” to the country, serving as “propaganda machines” that raise money for those private organizations while acting as “fake history sites” that obscure or erase the truth. This is what made Clark wonder whether our country’s current administration might have been different if those charged with administering the records had played a more reliable role in presenting presidential history.

He outlined the problem of personnel who would bow to the interests of private organizations that provide funding to these libraries, which he suggested might prioritize an exhibit that shows a president in a good light over fulfilling Freedom of Information Act requests, for instance. For someone in that position, it’s understandable they might worry — don’t do what the funders want, and maybe lose the funding, and the job — but Clark reminded the room that it’s more than a top-down change that’s required. Yes, he said, there should be someone who is “independently leading an independent agency.” But if the leader isn’t leading, then, he said, “they don’t deserve your industry,” and you should find a place that “respects and deserves” you, and become the kind of leader that others respect and deserve.

Clark’s passion for the topic was evident. It’s clear that his many years spent considering this so deeply have had an impact, and it seems he is understandably upset that he’s one of the few people who’ve done anything about his findings. Though I haven’t read his book yet, I can imagine that frustration comes through as clearly in his writing as in his speech. It’s a difficult position to be in. Here’s someone who spent more than a decade seeing issues first-hand and documenting a lot of problems in a system, but perhaps feels like he’s attempting to take down a goliath singlehandedly. As Sara A. Polak wrote in a review of his book in The Public Historian, “The exasperation here is problematic because it creates the sense that Clark is a strong proponent of one side in a quarrel, rather than a historian trying to provide a dispassionate perspective on a struggle between complex interests and important ideological choices.”

But maybe this is an important time to be passionate, and maybe Clark is in a unique position to do so. Or maybe, as he implied in his address, all of us as information professionals share that role, and it is more important than ever to be impassioned.

As Robert Jensen outlined in The Myth of the Neutral Professional, a reading for one of our recent classes, those who are in a position to control access to information are unable to be neutral. Whether it’s deciding which books to acquire for a library collection, or what programming is created, or what details are shared or not shared in an exhibit, political choices are part of an information professional’s job. For those working in presidential libraries and museums, allowing misleading or incorrect information to be presented to the public is a political choice. It might seem like a tricky position to be in, but it’s one that ethical guidelines remind us to be cognizant of. For instance, the Society of American Archivists’ Code of Ethics states: “Archivists should demonstrate professional integrity and avoid potential conflicts of interest. They strive to balance the sometimes-competing interests of all stakeholders.” In his address, Clark noted that the stakeholders of the presidential library system might appear to include the foundations that provide funding or even the former presidents themselves; however, he reminded us that the true stakeholders are the American people.

It’s a strong ethical question for anyone working in any information profession: Who is it that you truly serve, and are you doing all that you can to serve them? Or, as Jensen stated: “The appropriate question isn’t ‘Are you political?’ but instead should be ‘Can you defend the conclusions you reach?'” In the end, neutrality may not be possible, and for Clark, we may all be better off because of that.

Thankfully, forums such as this one exist to help information professionals consider the implications of political actions in the workplace. The Archivists Round Table is an excellent resource for bringing this community together to discuss complicated topics like this that are relevant to the profession, and they hold events throughout the year, which I look forward to attending more of.

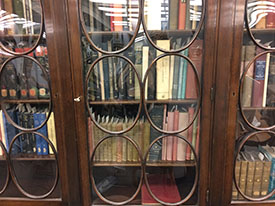

The Fales Library and Special Collections, located on the third floor of ElmerHolmes Bobst Library at

The Fales Library and Special Collections, located on the third floor of ElmerHolmes Bobst Library at  phone-logs, to art-objects, this collection contains the primary source materials for the topic of the discussion today,

phone-logs, to art-objects, this collection contains the primary source materials for the topic of the discussion today,  archive-based exhibition, discuss his kindred relationship with Wojnarowicz. He conveyed a deep understanding of the symbols of Wojnarowicz’ art that in part had developed through years of studying the materials on display.

archive-based exhibition, discuss his kindred relationship with Wojnarowicz. He conveyed a deep understanding of the symbols of Wojnarowicz’ art that in part had developed through years of studying the materials on display. which may have been used in Wojnarowicz’ early photo series, Arthur Rimbaud in New York. Archival material represents a sizable portion of the work on display. To name a few examples, there is an audio recording of a 1992 reading given by Wojnarowicz at The Drawing Center; a black and white unfinished film that was borrowed from the Fales Collection; and a vitrine containing a pamphlet from the American Family Association and the annotated Affidavit for David Wojnarowicz v. American Family Association and Donald E. Wildmon.

which may have been used in Wojnarowicz’ early photo series, Arthur Rimbaud in New York. Archival material represents a sizable portion of the work on display. To name a few examples, there is an audio recording of a 1992 reading given by Wojnarowicz at The Drawing Center; a black and white unfinished film that was borrowed from the Fales Collection; and a vitrine containing a pamphlet from the American Family Association and the annotated Affidavit for David Wojnarowicz v. American Family Association and Donald E. Wildmon.