For my event review assignment, I chose to attend The Museum of Modern Art Archives, Library, and Research Collections Fall Orientation on October 1, 2018. I was initially intrigued by this event because of the experience I’ve had working as a GA at the Pratt Institute Library in Brooklyn. There, I spend a decent amount of time paging artist’s books — which I learned often aren’t even books at all. One document I’ve come across actually most closely resembles a bag of flour. The experience of spending time in this environment (which is closed off from patrons and requires the assistance of library staff to access) has been interesting to me in that relates to some of my Knowledge Organization readings. (I still don’t know for sure if an antelope is a document, but I do understand how and why a bag of flour-looking piece of artwork is, and why it must be stored on an oversize bookshelf.)

If I am being completely honest, another driving reason I attended this particular event was that it lined up with my schedule. While I have always enjoyed my time visiting the MoMA, I did not study art/art history in undergrad, nor am I particularly interested in working in the art world upon graduation. Because of my general lack of interest in the area of modern art, I was surprised to find that many aspects of the event did prove quite interesting to me and very relevant to my LIS studies so far.

Several different staff members from MoMA’s archives spoke throughout the course of the orientation, which was largely a walkthrough of MoMA’s online catalog (called the DadaBase) and finding aids. They peppered in ample encouragement to obtain a MoMA library card (which is super easy to do). One person who spoke was in charge of long-term preservation of materials; essentially ensuring files don’t corrupt in storage and are migrated to formats that can still be opened in, say, 20 years. This entails making sure “.doc” files are changed (en masse) to “.docx,” for example. It made me think of points raised by Nick Krabbenhoeft, digital preservation manager at the New York Public Library, when he visited our class, like the storage aspects of the Open Archival Information System. Before starting the LIS program I had never thought of archiving as a constant process. I was taking for granted all that must happen in between a document being processed and later retrieved.

I found the presentation from Jenny Tobias, Reader Services Librarian, to be the most engaging. She explained that MoMA has 6.5 million “pieces of paper” in its holdings that supplement its collection and discussed the increasingly “fuzzy line between informational and artifactural.” The documents she described included correspondence between MoMA librarians and artists, which revealed greater context surrounding the exhibits these artists were putting on at the time.

“It just gives you the nitty gritty sense of how these artists were working and talking with each other and what their thought process was,” she said.

She added that there is an increased interest in archival materials within the museum field, and that MoMA has plans to intermix documents from its archives into its exhibits and permanent collection. This made me think of part of the Whitney’s recent exhibit “An Incomplete History of Protest,” which I really enjoyed. I was particularly interested in the letters on display that comprised “Strike, Boycott, Advocate: The Whitney Archives,” which were classified as “collective, artist-led engagement with the Museum”: essentially, letters written to the museum about planned strikes and boycotts. Some were letters from artists requesting their work be taken off display as a protest measure.

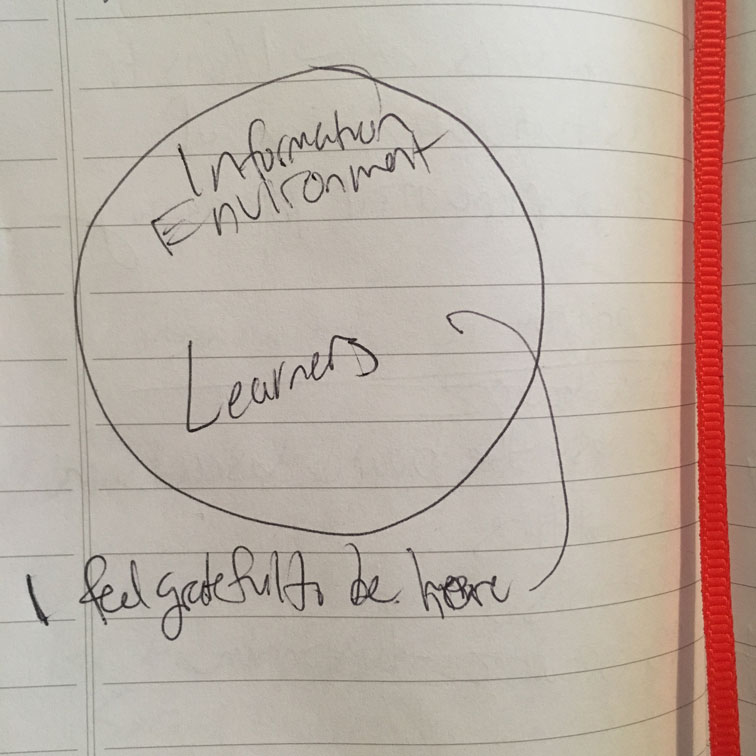

Tobias explained that she and her colleagues are currently in the process of going through the collections to “select things to digitize that represent works of art when there’s no object available, such as documentation of performances, or event scores, diagrams for how to assemble an installation, mail art, [or] visual correspondence.” She said that “these types of materials could themselves be considered artwork or represent[ative of] art.” This caused me to reflect on the 1991 article from Michel Buckland “Information as Thing,” which I read for my Foundations of Information class. Specifically, it made me think about the notion as information as process and information as thing. While information as process typically refers to the intangible, I feel that the evidence or documentation of process apparent in these types of documents is still pertinent. I somehow hadn’t made the connection between information as process and process art before attending this event, but this is now helping me conceptualize the actual value of process art in a new way. I suppose, however, that “information as thing” is a better comparison here. This connection caused me to think critically about what actually contains more information — a piece of artwork or the accompanying documents (e.g. visual correspondence surrounding the exhibit that the artwork was shown at it).

The Fales Library and Special Collections, located on the third floor of ElmerHolmes Bobst Library at

The Fales Library and Special Collections, located on the third floor of ElmerHolmes Bobst Library at  phone-logs, to art-objects, this collection contains the primary source materials for the topic of the discussion today,

phone-logs, to art-objects, this collection contains the primary source materials for the topic of the discussion today,  archive-based exhibition, discuss his kindred relationship with Wojnarowicz. He conveyed a deep understanding of the symbols of Wojnarowicz’ art that in part had developed through years of studying the materials on display.

archive-based exhibition, discuss his kindred relationship with Wojnarowicz. He conveyed a deep understanding of the symbols of Wojnarowicz’ art that in part had developed through years of studying the materials on display. which may have been used in Wojnarowicz’ early photo series, Arthur Rimbaud in New York. Archival material represents a sizable portion of the work on display. To name a few examples, there is an audio recording of a 1992 reading given by Wojnarowicz at The Drawing Center; a black and white unfinished film that was borrowed from the Fales Collection; and a vitrine containing a pamphlet from the American Family Association and the annotated Affidavit for David Wojnarowicz v. American Family Association and Donald E. Wildmon.

which may have been used in Wojnarowicz’ early photo series, Arthur Rimbaud in New York. Archival material represents a sizable portion of the work on display. To name a few examples, there is an audio recording of a 1992 reading given by Wojnarowicz at The Drawing Center; a black and white unfinished film that was borrowed from the Fales Collection; and a vitrine containing a pamphlet from the American Family Association and the annotated Affidavit for David Wojnarowicz v. American Family Association and Donald E. Wildmon.