By Char Jeré

Ruha Benjamin’s talk on Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code was just as raw as the topic itself. It came with no filters, no disclaimers and no trigger warnings— it wasn’t for the precious, it was for the people whose lives depend on such brutal honesty. This moment with Benjamin felt like an astral projection, the experience catapulting me from a space where darkness was being vilified to a place where it is now finally embraced. During this talk, it seemed like Benjamin was shepherding us out of our own black boxes of internalized racism and into clarity. After her three provocations, I was called to take a left out of my body and a right into my imagination—the directions were simple but you still needed to know them, as a right out of my body could have led me back into someone else’s imagination, essentially up the creek without a paddle. Benjamin stated that, “Most people are forced to live inside of someone else’s imagination”, citing Adrienne Marie Brown’s book Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds, as an inspiration. As Brown explains in her book, “I often feel I am trapped inside someone else’s capability. I often feel I am trapped inside someone else’s imagination, and I must engage my own imagination in order to break free.”. Power does indeed lie in the ability to imagine but what happens when you have an old, tiresome imagination that turns innocent people into potential threats, “superpredators” and even worse, demons? These words have all been weaponized by top political figures, from Hillary Clinton to killer cops (like Darren Wilson) against African Americans for centuries. Officer Wilson described Michael Brown as a demon before he brutally shot and killed the 18-year-old on the streets in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014. Audre Lorde would call such things “imagination without insight” in her essay “Poetry is Not a Luxury”.

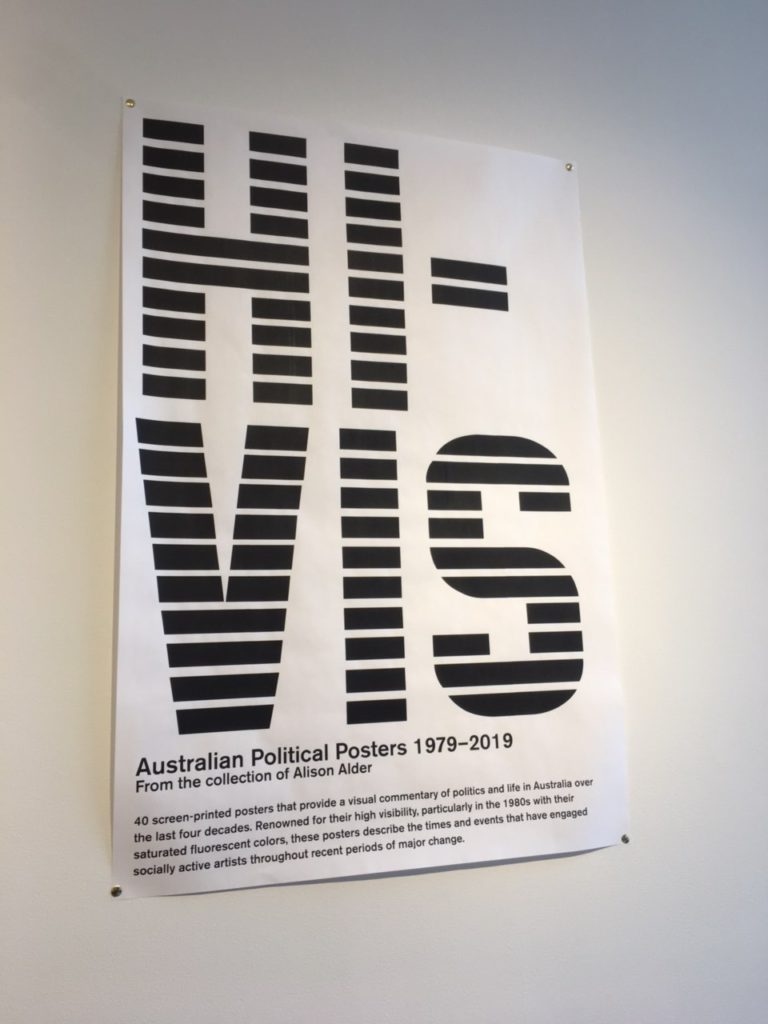

A photograph from the exhibit on African-American progress, on view inside the Palace of Social Economy at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris. (Library of Congress)

I started thinking more deeply about my daily interactions with intrusive, white-bred artifacts; Benjamin quoted Langdon Winner as saying “Artifacts have politics.”. The residues of white inferiority have been scattered strategically around us and are the default within the design and ultimately, within the system. White bias exists in so many facets of our daily lives that it often becomes disturbingly inconspicuous. Kara Walker states that with monuments and memorials, “…there’s this very peculiar quality that they have of being completely invisible— the larger they are, in fact, the more they sink into the background.” The effects of this phenomenon (white inferiority) were having fun double-dutching and hopscotching through my genes like school kids on summer break. Right there in my cold metal folding chair, I sat realizing that every new technology’s job was not only to reintroduce us to new trauma but to preserve the intergenerational trauma in my DNA. The matrix of oppression could be explicit but it could also be obscure; it could be abrasive while also being agreeable, moonlighting as a “serve and protector”. It was as disruptive as light is to darkness but useless against reason and true innovation. Ruha Benjamin pushes us to examine our interiority, so we no longer need to put up with the mediocrity of settler colonialism. She wants us to liberate ourselves so we can start truly innovating change. We are now impenetrable and have received our reparative vaccinations against white redundancy that have been killing and stagnating us for centuries. It is time to finally welcome modernity. In Safia Elhillo’s book The January Children, she references a quote by Adonis, “How many centuries deep is your wound.”. This was not a question–it was a critical examination of race, ethnicity, class and gender through rhetoric. My question is: when they colonize Mars, will racism still be en vogue?

I am the God of war! ARrrrrghhhh!!!!!

“THERE ARE BLACK PEOPLE IN THE FUTURE.” Alisha Wormsley’s billboard exclaims, hovering over an area in Pittsburgh that has seen rapid changes from “re-development” projects and gentrification. We are in the future just by existing in this present moment but for me it is not just about being there, it’s about where we are there. During the talk-back, people who were living in public housing explained that their landlord installed facial recognition software without their consent. They also expressed concern about their right to privacy. New technology has never been empathetic to the needs of marginalized people, which means that designers do not envision us in the future. Firearms, steam engines, the Cotton Gin and the internet are all examples of how technological advances keep oppression well-fed. As Benjamin shifted her talk from the well-documented problems of white technological setbacks to solutions on how to mobilize against these “New Jim Codes”, she states this: “Like abolitionist practices of a previous era, not all manners of resistance and getting free should be exposed…calls for abolition are never simply about bringing harmful systems to an end but also about envisioning new ones…”.

(Image courtesy of Jon Rubin)

People who have been marginalized and made the most vulnerable are constantly working and fighting to adjust their user settings, in turn causing them to consistently relive their own trauma. Benjamin declared, “The nightmares that many people are forced to endure are the underside of elite fantasies about efficiency, profit, and social control.”. Her declarations are the tuning forks of knowledge–they are our first post-apocalyptic radio broadcast that blares the coordinates of liberation. Benjamin shows us that there are more of us out there, imagining and creating outside of the logics we had internalized; we are building our own micro-revolutions. She reassures us that nothing is permanent, especially not oppression. In thinking about what some historians call “slave-breeding”, or coerced sexual-reproduction (eugenics) during slavery in the Americas, instead of UXD, I started repeating “HXD, HXD…HXD,” for Human Experiment Design, or more specifically, the process of manipulating human behavior and genetics through brutality, mortality, and corporeality. People have been and still are being domesticated like animals and plants, which has real-world implications. The whip, the gun, the white man and capitalism are all clinging tightly to our cells like a gene mutation.

There was a sense of urgency in Benjamin’s voice that activated the ancestor memory card deeply embedded within my DNA, sending RNA and Cas9 by way of gene-drive technology to isolate trauma, cut it out and be rid of it once and for all. The idea of eliminating white inferiority from our genetic coding is liberating but to think that we possess the power to free our ancestors who came before (and will surely come after) has started to consume me. She pointed to Pierre Bourdieu as saying that, “the way you know you have a powerful system is that you no longer need the conductor, people just orchestrate themselves. You internalize it and [that’s how] we keep it going.”. She goes on to say that colorism is not perpetuated in the black community or other communities of color by a white man standing there and saying “you are better, you are worse, you are more valued…it’s through the internalization of the logic that we continue to reproduce amongst ourselves.”. Suffering is a trillion-dollar, sadistic business that finds joy and comfort in exploiting pain—capitalism relies heavily on its reproduction through the germ cell lineage. We have no choice but to disrupt this industry by denying it access to the next generation.

The night of the talk, Benjamin felt like Morpheus from the Matrix but she didn’t give us the option to be complacent anymore; there was only one pill. The doors of the Housing Works were the threshold of the linear perception of time; walking through them meant there was no going back. We were all accountable because we were now all armed with the knowledge and inspiration to bring about our own insurrections. There was an energy in the room that I hadn’t felt since my radical Black feminist seminar in undergrad, which was both optimistic and restorative. When Harriet Tubman walked by a plantation singing “Steal Away” and “Sweet Chariot”, that was her way of communicating that it was time to move and time to break free. Likewise, when Ruha Benjamin took the stage, her provocations were like the songs of the Underground Railroad, her last being the most profound: “The imagination is a contested field of action, not an ephemeral afterthought that we have a luxury to dismiss or romanticize but a resource, a battleground, an input and output of tech and social order.”.

Sources:

http://ennemareebrown.net/tag/imagination/

Lorde, A. (1984). Sister outsider: Essays and speeches. Trumansburg, NY: Crossing Press