THE FUTURE OF THE BOOK

NYU recently hosted an NYU Media Talk of the topic The Future of the Book. The panel included speakers from the publishing industry, as well as the director of strategic partnerships at Google, Tom Turvey, who manages Google’s content licensing arrangements with all print media companies globally (including books, magazines, news and journals). Google is, of course, the gorilla in any book publishing/library room, with ambitious plans through Google Books: “Our ultimate goal is to work with publishers and libraries to create a comprehensive, searchable, virtual card catalog of all books in all languages that helps users discover new books and publishers discover new readers.”[1] In addition, Google is working with 20 library “partners,” including (in New York) Columbia University and the New York Public Library in their Library Project.

In addition to Google’s Tom Turvey, the panel included a publisher who discussed the growing importance of self-published authors to the bottom line of Simon & Schuster’s Atria Publishing (Judith Curr, President and Publisher, Atria Publishing), an author/producer of television/editor and President of Random House Studio (Peter Gethers), and the VP and Director of John Wiley and Sons Business Development, Global Digital Books division (Peter Balis). All spoke of the need to connect books/authors with readers. As publishing is changing, the traditional progression of a “work” from the author’s brain to the reader through layers of agents, editors, publishers and librarians is changing. The way that readers learn about books they may want to read is also evolving quickly. All the panelists discussed the crucial role for authors of self-promotion, and of the power of bloggers to reach readers.

One theme that emerged was the importance of access to readers. The discussion pointed out that booksellers are contracting, advertising in traditional print media reaches fewer readers. As stated above, Google’s project, ambitious in scope, proposes to put ALL books in a keyword-searchable form, with access to Tables of Contents and preview pages available. Turvey said that Google has expanded into 30 countries with this effort. He talked about the difficulties that arise when the different members of the project lack international cataloging standards.[2]

The primary concern cited by the panelists revolved around finding new ways to connect readers to their audience. A growing number of authors begin by expanding their online recognition, working the social media by blogging, tweeting and Facebook. These authors frequently self-publish. Once they demonstrate that they have an extensive following that buys their books, they can get a publisher interested in their work. A publisher can leverage that public exposure and interested, loyal fan base by becoming the author’s publisher and by searching for other outlets such as television and film for the author’s work. Atria’s publisher spoke of working to create a “community” of self-published authors and their readers as a way to publicize and sell more books. Random House Studio’s Gethers spoke of the importance of flexibility in selling and marketing authors. His company has increased the types of projects to which authors can be attached. Random House is aggressively seeking television, documentary and fiction film projects for their authors. One cookery blogger became a self-published cookbook author and then a Random House author with a cable-based cooking show.

Some of these trends in publishing appear to democratize publishing by allowing pathways for more authors to directly reach readers, without the (arguably elitist) intervention of the gatekeepers of the corporate media world and the libraries. In a world without gatekeepers, though, the amount of published material increases and guidance for readers by their traditional “curators” like booksellers and librarians becomes harder to find. The difficulty becomes the evaporation of a crucial part of reader engagement: trust. Few publishers have built that trust directly with readers; Gethers mentioned Penguin UK and Harlequin as examples of publishers who have done so.

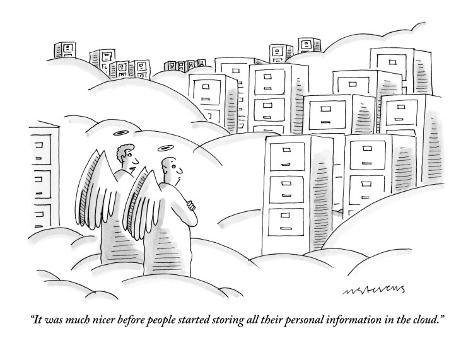

It is easy to imagine readers becoming increasingly reliant on Google-style searches to find books and access them, either by buying them or by borrowing them, either as e-books or as printed books. Libraries are under pressure to provide comparable search capacity in their catalogs, and private vendors already are available to contract those services for libraries.[3] It seems highly likely that book-related searches will be treated as highly valuable information commodities by Google, by publishers or other corporate interests and even, possibly, by libraries. While libraries have, in the past, resisted the pressure to reveal to the government the nature of library user’s book searches and borrowing histories, pressure may mount. In Liquid Surveillance[4], the authors discussed the increase in a sort of self-surveillance by participation in the online and remote consumer and credit networks. Consumers’ ability to search for books and to link to book resources remotely may provide just the opening that government surveillance seeks.

[2] http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/trade-shows-events/article/60063-at-nyu-experts-debate-future-of-the-book.html

[3] Faiks, A., Radermacher, A. and Sheehan, A., “What ABOUT the Book: Google-izing the Catalog with Tables of Contents, Library Philosophy and Practice 2007, LPP Special Issue on Libraries and Google.

[4] Bauman, Zygmunt and David Lyon. (2013) Liquid Surveillance: A conversation. Cambridge: Polity Press.