Due to a friends recommendation, I recently visited the Museum of the City of New York to learn more about the city I’ve been living in for the past 4 years. New York City is so rich with history and culture, that mentioning NYC to anyone can bring up a different range of emotions, feelings, and thoughts. The Museum is filled with close to 450 historic physical objects and images as well as contemporary video, photography, and interactive digital experiences that give an insightful and intimate look of New York City from it’s early beginnings to now.

As I walked into the museum I was immediately introduce to an exhibit called “New York at Its Core”. This exhibit, in a nutshell, answers the question of “What makes New York New York?”

The exhibit covers the history of New York from 1609 through 2012 with various sections dedicated to specific timeframes each with supporting artifacts. Framed around the key themes of money, density, diversity, and creativity, New York City’s history and future come alive in this first-of-its-kind exhibition, through the stories of innovation, energy, struggle, and the vision of generations of immigrants, politicians, tycoons, dreamers, master builders, and ordinary New Yorkers. [MCNY]. I specifically liked how this exhibit used both physical and digital objects to illustrate and inform visitors of the rich history of NYC. More on the use of interactive screens later.

A few floors above, I was excited walk through the Jackie Robinson exhibit, “In the Dugout with Jackie Robinson”.

The avid baseball fan in me was excited to see the various memorabilia and rare footage (video and photos) of Jackie Robinson and his family, as well as the published magazines covers and articles from popular publishers outlining his career and life story. The collection of materials gave an intimate portrait of a baseball legend struggles, challenges, obstacles, and success on and off the field. This exhibit in some ways made me think about how each person has a story and it can be documented by the person and people around them that gives a glimpse into the past.

As I walked through these museum, I noticed the variety of people (races, ages, gender, etc), exhibits/collections and how they intersected and connected us (as people and visitors). It reminded me that even if you aren’t an avid baseball fan or from NYC, museums bring together people from different backgrounds, forms connections, and educates (or informs) them about topics that they may not have known or interested in. Museums are unique in that they tend to offer a neutral place for discussion, thought and experience; similar to libraries they can serve as a platform for promoting innovation within our communities. Of course the degree of education by these institutes are based on how well they are curated, the type of content they contain and the more, importantly, willingness/openness the visitor is to receive information. Not only is it important to enable the passing of information but also enable the reception/receiving for it (i.e. via technology or learning how to interpret/process information as a user/visitor).

Reinforcing Bucklands ideals, museums are a great example of Information systems and the physical objects within them are great examples of Information-as-thing. Moreover the Museum of the City of New York itself is a document. But what is a document, according to Buckland, by definition a document is any source of information, in material form, capable of being used for reference or study or as an authority. [Buckland] The concept of “document” opens up a broader perspective, which creates, rather than limits understandings of the human relationship with information. This expanded concept of “document” as sign/semiotic helps us understand user experience in ways not previously explored in the convergence of museums and information studies. [Lantham]

Neither information-as-process nor information-as-knowledge are considered tangible because they cannot be measured or touched. [Buckland] In order to use, manipulate or handle information, we must communicate it. Information can be so large and vast, no matter what form it takes whether digital or physical, that it can be quite overwhelming when viewing or consuming it, regardless of the setting (library, museum, book, internet, etc).

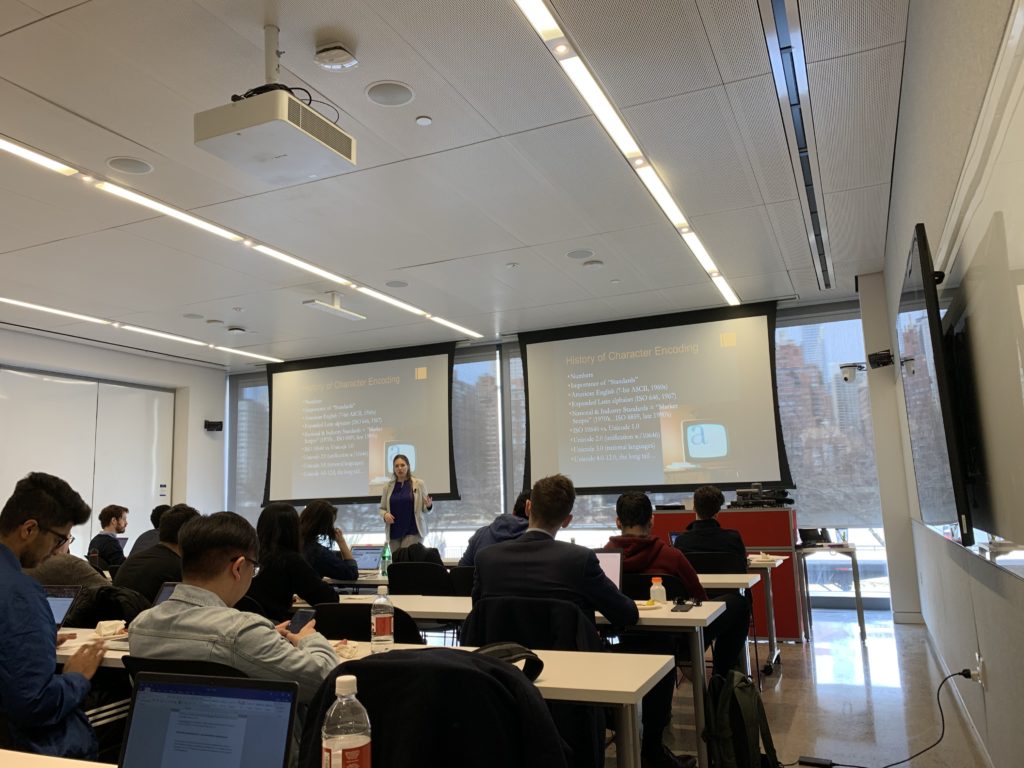

Museums, specifically, are curated in a way that allows information to be accessible without overbearing the user/visitor. I never really though of User Experience in the field of libraries or museums as I naively thought of UX only in the field of computers. An example of how technology is changing the way museum and visitor engagement is changing is with the introduction of interactive screens. In the “New York at Its Core” exhibit at The Museum of the City of New York, there are interactive elements that introduce visitors to 70+ historical figures who represent New York City’s characteristic diversity such as Jean Basquiat, Patti Smith, Joel Ross, etc. See image below for reference.

As described by Don Norman in the Design of Everyday things, these interactive elements are extremely effective and its use of affordances, signifiers, immediate feedback, and mappings presents a strong example of user-centered design. They are easy to use and understand for people of all ages and abilities and has a simple design that enables discoverability of the countless amount of information.

In closing, as technology changes and how people consume information, so will industry and institutions change. Museums are having to adapt to these changes not necessarily out of reluctance but necessity and are beginning to embrace new forms of communication, storytelling, and engagement.

Bibliography

Museum of the City of New York, Available online: https://www.mcny.org/nyatitscore [Accessed on April 10, 2019]

Micahel Buckland, Journal of the American Society of Information Science48, no. 9 (Sept 1997): 804-809

Kiersten F. Latham, “Museum object as document: Using Buckland’s information concepts to understand museum experiences”, Journal of Documentation, Vol. 68 Issue: 1, pp.45-71,https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411211200329