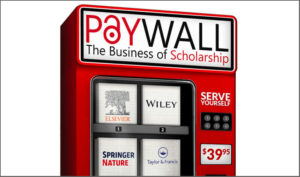

On Thursday, September 20th, I went to the NYU Cantor Film Center to watch the screening of the new documentary film Paywall: The Business of Scholarship directed by Jason Schmitt, a communications and media scholar at Clarkson University, New York. Paywall is a 65-minute film which seems to advocate for the need of open access (OA) practices that lack in the academic publishing industry focused on research and science. The documentary weaves two overarching inquiries: it examines the 35-40% profit margin associated particularly with Elsevier and other top academic publishers and compares this with the incomes of the most profitable tech companies like Apple, Facebook, and Google. The film also questions the high financial costs of subscription-based academic journals and how scholarship and innovation in general is affected by these costs when scholars, students, and researchers hit paywalls that deny them access to the most updated research.

The format of Paywall is presented through sequenced interviews of a wide range of scholars, publishers, and OA advocates from across the world. One of the key issues that strucked me of the interviews is when I learned that most scientific research is publicly funded by government agencies or universities, and yet this research is locked behind expensive paywalls and kept from access to the general public. It was also surprising to see why the academic publishing industry is extremely profitable. John Adler, a professor of neurosurgery at Standford University who appeared early on in the film, said “publishing is so profitable because workers do not get paid.” He referred to workers as the people who create the products for academic journals – authors and reviewers. This brings to question how come writers do not get paid for their services and how is this business model sustainable for them?

While the documentary do not delve into the perspectives of authors and scholars who provide their labor to academic journals, it examines the way top publishers have sustained their business model in the market. They have made themselves indispensable to their clients, in this case universities, with a set of policies that allow them to be excessively profitable. Some interviewees in the film including library professionals, explain that universities are required to keep in confidentiality the costs they pay for subscription-based academic journals. In this way, publishers can charge any rate to each university without revealing their different charging practices with other schools, which prevents others to compete against them. Universities also lack the power to decide which journals they should buy or should not because they need all the latest scholarship work that is controlled by legacy publishers such as Elsevier, Wiley, Springer Nature, and Sage.

These issues with control and power over information exerted by top publishers brought me back to Robert McChesney’s ideas in Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism is Turning the Internet Against Democracy when he discusses the political economy of communication (PEC). The author explains that the PEC examines the institutions, market structures, support mechanisms, and labor practices that define a media or communication system, and determines whether those practices are conducive or not to democratic values. For instance, McChesney analizes the case with Microsoft which has become a proprietary software company indispensable to society. The reading states that “Microsoft has been able to exploit the dependence of a wide range software applications on its underlying operating system in order to lock in its system permanently, allowing it to enjoy long-term monopoly-pricing power. Any competitor seeking to introduce a new rival operating system, faces an enormous ‘applications barrier to entry’ ” (p. 73). This business model of dependency and monopoly aligns with they way academic journals have also employ their power with paywalls. A model that interferes with the progression of a modern democracy.

Schmitt’s film also addresses the negative consequences of paywalls to broader societal issues. Two medical doctors from Nepal and Nigeria who participated in the interviews testified the experiences of students in their countries with subscription-based journals. They mentioned that paywalls deny students access to the latest literature and this prevents the professional development of students and contributions to their field to happen. This exclusion is due in part for the high costs of paywalls that do not correspond with the inequities of the currency of countries from the developing world. Therefore, this is harmful not only for them and researchers from the developing world, but also for scholarship itself. A vital aspect of scholarship is innovation and this flourishes when a great diversity of people and knowledges contribute to it.

Although most Paywall’s interviewees seemed to support the idea that society would be better if scholarly articles are distributed in an open access world, the documentary do not explore adequately the challenges that OA publishing would face – the costs and risks associated with it. Additionally, the film does not address the reasons why scholars choose to sign away their rights to their scholarly work to commercial publishers, instead of making their papers freely available to their academic institutions. This question is brought up in Siva Vaidhyanathan’s article Critical Information Studies: A Bibliographic Manifesto which states that academics frequently “overreact to perceived ‘threats’ that someone is teaching ‘their’ course or relying too heavily on ‘their’ data.” Vaidhyanathan also mentions that “[t]oo often, academic leaders forget their ethical duty to the community of scholars and world citizens at large. Their rabidly protect their ‘intellectual property’ to the detriment of the scholarly world (an the species) as a whole…” (p. 26). These issues helped me to be more aware of the complexities that scholarship work entails.

After watching the screening, there was a discussion among the audience mediated by NYU librarian April Hathcock. She started the conversation by asking us if this making-money business mindset belongs in to academic scholarship? Rather than providing answers in the room, there were more questions from the audience regarding advocacy, research efficiency, inclusivity, copyrights, commerce, quality, and innovation. A NYU PhD student referred the example of Sci-Hub, which was featured in the film, as a tool that helps him to find academic papers more easily and faster than the academic journals he is able to access through his university. He suggested that Sci-Hub’s website is more user-friendly and seamless. It was interesting to hear this perspective from a student who has the privilege to access to the most updated information in research from top subscription-based journals. His comment left me with questions regarding deficiencies of the website development and interface design of academic journals.

References

Paywall: The Business of Scholarship. Retrieved September 27, 2018, from https://paywallthemovie.com

McChesney, R. W. (2013). Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism is Turning the Internet Against Democracy (pp. 64-66, 73). New York: The New Press.

Vaidhyanathan, S. (2005). Critical Information Studies: A Bibliographic Manifesto (p. 26).

References

References