Category: Articles

Bringing the Cloud Back Down to Earth

BY BLAIR TALBOT

On Sunday, October 20th I attended the Radical Networks conference and attended two talks: The Carbon Footprint of the Internet with Jasmine Soltani and Everything has a Resonant Frequency: Crystals, Networks, and Crystal Networks with Ingrid Burrington. Both talks covered a lot of ground (or rather, earth) on the sweeping topic of the environmental impact of the Internet and the manufacture of its physical infrastructure by two very broad thinkers whose research has forged ahead in areas where concrete data is hard to come by. For clarity and concision, I will focus on my main takeaways from the first talk, the Carbon Footprint of the Internet.

Soltani began her talk by explaining the bottom-up approach she and other activists have taken to calculating the carbon footprint of the Internet in the absence of definitive, trustworthy sources: identify all the components and processes that make up the Internet, calculate the energy consumption of each, and identify the energy sources of each and convert that energy amount to the CO2 equivalent. To date there still exists no surefire way to calculate the carbon footprint of the Internet, and therefore estimates of the energy intensity of the Internet diverge by a factor of 20,000, which can in part be explained by different definitions of what the Internet is and what it includes (Hilty & Aebischer, 2015).

Current estimates state that the Internet accounts for about 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions (Belkhir & Elmeligi, 2018), which is both significantly less than what I would have predicted and still too abstract to comprehend. For comparison, in Greenpeace’s suspiciously optimistic 2014 report on renewable energy and the Internet, Clicking Clean: How Companies are Creating the Green Internet, the authors state that if “the Cloud” were a country, it would be the 6th largest consumer of electricity on the planet (Cook et al., 2014).

One fact that is generally agreed upon is that the most energy consumptive element of the Internet is the manufacture and maintenance of its physical infrastructure, beginning with client devices (49%), Telecom infrastructure (37%), and data centers (14%; The Climate Group, 2008). For example, client devices, which refers to all of the devices we use to access the Internet (mobile phones, tablets, laptops, desktops, etc.) account for the highest proportion of energy consumption; depending on the study, estimates vary from 40% (Belkhir & Elmeligi, 2018) to 53% of the total energy consumption of the Internet (Raghavan & Ma, 2011). Most of this energy consumption is due to the manufacturing phase of client devices (referred to variously as either Embodied Energy or Grey Energy) and accounts for 45-80% of the total device life cycle energy (Hischier et al., 2015).

There are numerous complications with this measure and others like it because not all of these devices are used to access the Internet 100% of the time—someone can use a laptop to write a paper, for instance, without ever using the Internet, nor are device lifecycles consistent across all users—one person can use a phone for 6 months and another for 6 years. These are just some examples of the nuances that make definitive calculations about the carbon footprint of the Internet very difficult, if not impossible. (Ingrid Burrington touches on the difficulties these metrics pose in her article “The Environmental Toll of a Netflix Binge” in The Atlantic.) I found Soltani’s research commendable because despite the scarcity of data available and the opacity of the data that does exist, she has forged ahead and brought attention to this timely topic.

What was also surprising about her talk—and where she differs substantially from Burrington—is she remains optimistic about the overall positive impact that the Internet could have in reducing net carbon emissions in other sectors despite the Internet’s own significant contributions to global greenhouse gas emissions. While she herself strays away from a techno-optimist stance, she does cite some suspiciously sanguine (and perhaps outmoded) views, such as those from an optimistic 2008 report by The Climate Group: “The scale of emissions reductions that could be enabled by the smart integration of ICT into new ways of operating, living, working, learning and traveling makes the sector a key player in the fight against climate change, despite its own growing carbon footprint,” (The Climate Group, 2008). As an example of this, she mentioned that teleconferencing takes about 7% of the total energy cost that a face-to-face meeting would, taking into account factors like different modes of transportation, etc. (Ong et al., 2014).

She does concede that other examples of the “dematerialization” of information, including the move from traditional modes of music and movie distribution to digital streaming platforms, have less of a positive environment impact: depending on the study, streaming video is either only slightly more efficient than DVD distribution (Shehabi et al., 2014), or has an even higher net energy impact that is still rapidly increasing (The Shift Project, 2019). Whatever the exact figure is, it is highly impactful due to the fact that video streaming accounts for 64% of all internet traffic (Ejembi & Bhatti 2015).

The onus of finding environmentally sustainable solutions to this predicament we are all in should undoubtedly lay with the tech companies and governments with the greatest carbon footprints, and not on individuals. If one trusted the government to oversee the private sector, we could take inspiration from Paul Ford’s proposal to establish a government agency which he calls the Digital Environmental Protection Agency, responsible for protecting citizens in the event of repeated “data spills,” (Ford, 2018). How fitting, then, to also imagine tasking this hypothetical branch of a rotten bureaucracy with the additional task of disciplining the tech industry and cleaning up its messes.

Despite the absence of government legislation and private sector self-regulation, Soltani says that individual consumers can also take action. Her suggestions include extending the life of your client devices, using ad blockers (online advertising is very energy consumptive), protecting your data privacy (the storing of your personal data is also energy consumptive), and “stream lower quality videos, I guess,” (Soltani, 2019). All of these actions, save for electing to stream grainy YouTube videos, are all actions that have manifold benefits for consumers: less money spent on replacing devices and less personal data being collected, stored and sold to marketers and insurance companies at our citizenry’s expense.

While these actions she suggests may benefit individual consumers and make a small environmental impact, they do nothing to challenge the structural logic of late techno-capitalism and its extractivist methodology. Capitalism has always benefited from the dislocation of earth materials from Earth, the dematerialization of commodities and the invisibilization of labor. What is unprecedented at this stage of capitalism is that these existing abstractions of capitalist production have themselves become further abstracted and etherealized in the image of the Cloud. The semiotics of the Cloud further mystifies the terms of commodification and shrouds its mechanics in a blanket of mysticism. Divorcing the Internet from the materiality of the Internet in the image of the Cloud directly benefits the Internet’s profiteers and limits people’s ability to see the ideological machinery at work in their daily lives.

To uncloak this mantle of mysticism surrounding the Cloud, Nathan Ensmenger proposes treating the Cloud as a “type of factory” and interrogating it as such:

[W]hat kind of a factory is it? Who works there, and what kind of work to they do, and how is it different from the type of work previously performed by factory workers? Where does it fit in a larger technological, labor, and environmental history of human industry? And perhaps most importantly, how did it come to be seen as categorically different? (Ensmenger, 2018, p. 20)

This historical-materialist critique of the Cloud is a promising start towards resituating the Internet in its material, political, social, and cultural context. Only by bringing the Cloud back down to Earth can we begin to imagine a more equitable distribution of power in our hyper-networked reality.

POSTSCRIPT

This talk raised many questions I am still grappling with weeks later. As libraries and cultural centers move towards digitizing their assets and moving more and more services online, endeavors often hailed as universally beneficial and in line with our coupled missions to make information more accessible and to preserve it for posterity, we do so with little to no heed for how this impacts our shared environmental future. When environmental collapse comes to a head it won’t matter if our books are conserved in print format or preserved digitally. As long as the lifecycles of the hardware we’re using to preserve digital formats continue to physically deteriorate, and the software we use for the same mission continues to rapidly accelerate, information professionals are forced to continually endeavor on the perilous journey of continuous data migration, making us complicit in the whole system of filling the earth with toxic, obsolete electronic equipment and mining the same earth yet again for more rare minerals to inaugurate another terminally obsolete technological lifecycle, ad infinitum. Infinite, that is, until we run out of minerals.

“Looking from the perspective of deep time,” Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler write in their essay on the human labor and planetary resources required to operate an Amazon Echo, “we are extracting Earth’s history to serve a split second of technological time, in order to build devices that are often designed to be used for no more than a few years,” (Crawford & Joler, 2018). All media is an extension of the earth, be it codices made of paper manufactured from trees which took hundreds to thousands of years to grow, or be it a PDF viewed on a laptop composed of lithium, cobalt, and silicon (and the 14 other rare earth minerals necessary to manufacture a single laptop or smartphone) that took billions of years for Earth to produce. Where we now differ from Gutenberg’s time is the dizzying rate of acceleration at which we are moving towards total depletion of the earth materials needed to produce the information communication technologies that are embedded in the infrastructure of every branch of daily life.

REFERENCES

Belkhir, L., & Elmeligi, A. (2018). Assessing ICT global emissions footprint: Trends to 2040 & recommendations. Journal of Cleaner Production, 177, 448–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.239

Burrington, I. (2015, December 16). The Environmental Toll of a Netflix Binge. Retrieved from The Atlantic website: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/12/there-are-no-clean-clouds/420744/

Cook, G., Dowdall, T., & Wang, Y. (2014). Clicking Clean: How Companies are Creating the Green Internet [Greenpeace USA report]. Retrieved from Greenpeace website: https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/wp-content/uploads/ legacy/Global/usa/planet3/PDFs/clickingclean.pdf.

Crawford, K., & Joler, V. (2018, September 7). Anatomy of an AI System. AI Now Institute and Share Lab. Retrieved from http://www.anatomyof.ai

Efoui-Hess, M. (2019). The Unsustainable Use of Online Video. Retrieved from https://theshiftproject.org/en/article/unsustainable-use-online-video/

Ejembi, O., & Bhatti, S. N. (2015). Client-Side Energy Costs of Video Streaming. 2015 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Data Intensive Systems, 252–259. https://doi.org/10.1109/DSDIS.2015.49

Ensmenger, N. (2018). The environmental history of computing. Technology and Culture, 59(5), S7–S33.

Ford, P. (2018, March 21). Facebook Is Why We Need a Digital Protection Agency. Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-03-21/paul-ford-facebook-is-why-we-need-a-digital-protection-agency

Hammond, R. (2009, April). In search of Lithium: The battle for the 3rd element. Retrieved from https://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/moslive/article-1166387/In-search-Lithium-The-battle-3rd-element.html

Hilty, L. M., & Aebischer, B. (2015). ICT for Sustainability: An Emerging Research Field. In L. M. Hilty & B. Aebischer (Eds.), ICT Innovations for Sustainability (pp. 3–36). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-09228-7

Ong, D., Moors, T., & Sivaraman, V. (2014). Comparison of the energy, carbon and time costs of videoconferencing and in-person meetings. Computer Communications, 50, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comcom.2014.02.009

Raghavan, B., & Ma, J. (2011). The energy and emergy of the Internet. Proceedings of the 10th ACM Workshop on Hot Topics in Networks, 9. ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2070562.2070571

Shehabi, A., Walker, B., & Masanet, E. (2014). The energy and greenhouse-gas implications of internet video streaming in the United States. Environmental Research Letters, 9(5), 054007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/9/5/054007

Soltani, J. (2019, October). The Carbon Footprint of the Internet. Presented at the Radical Networks Conference 2019, New York, NY.

The Climate Group. (2008, June 30). Smart 2020: Enabling the low carbon economy in the information age (pp. 1–87). https://www.theclimategroup.org/sites/default/files/downloads/annual-report-2007-2008.pdf

Interview: UX & its social concerns

I recently had the opportunity to interview Nina Mistry, the co-founder, and chief product officer of Artistic License Creative. She has been connected to the UX filed for more than two decades and my interview goal is to gain insights about what drives this profession today and her understanding of technology within our social realm. Artistic License Creative is a start-up that is driven by social change and innovation through the medium of digital technology. While the company is based in Toronto we met on her recent visit to New York where she shared her views on the UX field and social concerns surrounding it.

I had prepared a set of questions to structure the interview and almost all areas of interest were covered. It started with sharing details about herself and how she landed in the UX field. She is originally from Mumbai, India where she completed her undergraduate education in textile design. She graduated in the year 1999, a year where the internet had landed in most of our households. She believes that it was the internet that helped people become entrepreneurs overnight. “It made the whole world become your market,” says Nina. Her first job was as a designer at a small scale e-commerce company in India. After this, she went on to work with the software development team of interactive television that revolutionized live voting in India. She has also contributed to the design of the Target app and continues worked on many such projects even today.

Nina believes the whole idea of UX truly came to life when Apple launched its iPhone. She believes that the Iphone’s scroll user experience with the pinch and scroll and embedded keyboard scroll were game-changers in the field of technology. This is when design moved beyond its aesthetic principals and become an interactive experience. Her company Artistic License Creative (url in references) emphasizes on delivering content and experience(i.e. ways the content is consumed. Her company collaborates with people and works on projects that are driven by a cause. Whether it’s making documentaries, e-learning platforms websites or mobile applications they are driven by the purpose of making a difference.

Nina believes that it’s her curiosity and love for simplicity that makes her a relevant UX designer today. She thrives on the fulfillment derived by watching users use, react and cherish her designs. “Watching my vision materialize into an experience is the best feeling ever,” says Nina. The field design experience today seems to be divided into two distinct fields the User Research and User Experience field. When asked about this categorization she expressed that the main goal of a designer should seek solutions and there should be no distinct dividing lines in the process. The research process builds curiosity and sets a solid foundation for the design process.

Her research process mainly includes interviews and observations. Nina says “Sony conducted a focus group for their boom box. When asked about the color preference 70% picked black with 30% picked yellow. At the end of the session, participants were given the boom box as a gift for their participation and had to pick it up on their way out. All participants picked the black one. When people are observed they behave differently. It’s usually not what they say.” This relates to McGrath, “Methodology matters” reading which discusses the limitations of research. The article talks about how the limitation of one method can be covered by another and how using more than one research method would help in more realistic insights. For example, Sony’s interview flaw was coved by observing the audience making a realistic choice in person.

Furthermore, her design process is driven by the AGILE method which involves quick sketching, user testing and validation followed by multiple iterations. She says “more than a design process, it’s a co-creating process. It’s not just about user opinions but you think like the user.” We then moved on to discuss any specific experience or innovation that has caught her eye in recent times, she stated that a big influencer to determining this is how ethically the product is made and functions. When further asked about unethical innovations of technology today she discussed the emotional impact of Instagram’s need for maximum likes for validation leading to anxiety to FaceBook’s “fake news” targeted at psychological warfare. This connects to our discussion on Vaidhyanathan’s, “Anti-Social Media” which suggests only a limited online newsfeed for it’s its user. Nina re-iterated Vaidhyanathan’s take on users being oblivious to counterclaims taking away the reality of the situation.

She states Aza Raskin, the creator of the infinite scroll says that he “regrets creating it in the first place.” Elaborating more on the infinite scroll she states the user is targeted with ads and news aimed to change their opinion. And the common user is taken for granted and exploited for their lack of awareness. Nina states Google having all our information from our bank accounts to our heath records is unethical. And stresses that the “I agree to the terms and conditions check-box that people check is the biggest lie, as if you read the terms you would probably not agree.” This again connects to Shoshana Zuboff’s “surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization” which discusses our lack of privacy as a price we pay or collateral damage for using technology.

When asked about threats associated with design in the future Nina mentioned that the biggest threat with artificial intelligence and machine learning replacing human jobs. What kind of jobs would humans do it machines do most of what we do today? How will we adapt to this change? Would third world countries even have the infrastructure to adapt? She predicts that there will come a time where there will be no jobs leading eventually leading to an economic setback.

To conclude, speaking to Nina was a great way to validate all our class discussions associated with technology and social concerns. Nina was open and thrilled to answer all the questions. She made it a fun discussion where we both were sharing our views and adding on to each other’s arguments. Overall, she concluded with saying as a young aspiring design professional one should always have the wonder and curiosity along with seeking ethical solutions. “Be less motivated by monetary gains and more motivated by social good.” She concluded.

References

- Vaidhyanathan, Siva. Antisocial media: How Facebook disconnects us and undermines democracy. Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. “Big other: surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization.” Journal of Information Technology 30, no. 1 (2015): 75-89.

- McGrath, Joseph E. “Methodology matters: Doing research in the behavioral and social sciences.” In Readings in Human–Computer Interaction, pp. 152-169. Morgan Kaufmann, 1995

- Artistic License Creative. Accessed November 19, 2019. https://artisticlicensecreative.com/.

Impact of Social Media on the Youth

INTRODUCTION

Social Media has become an important part of our society that it is impossible to imagine our lives without it. Every other person is part of one or many social media platforms, some of the most popular ones being, Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram, WhatsApp, and YouTube. People, especially youth prefer to socialize through these platforms where you can interact with people from different parts of the world by just a click of the button. From giving us new ways to come together and stay connected to the world around us, to providing an outlet for expression, social media has fundamentally changed the way we initiate, build and maintain our relationships. As the popularity of social media is spreading all over the world, there have been mixed feelings about these networking sites.

My quest on how and to what extent social media is impacting the youth, led me to conduct a survey as well as an interview targeting an audience of 17 to 24 years.

I was able to conduct a detailed questionnaire which was responded by 12 participants along with an interview with two persons. The participants’ occupations were mixed – both professionals, as well as students, were part of the research process.

FINDINGS

From the research, I was able to gather, that most of my participants used social media networks such as WhatsApp, YouTube, Instagram, and Facebook.

There are both positive as well as negative impacts of using social media. It is necessary to talk about both sides of social media in order to get an overall idea of the research findings. First, let’s discuss some positive impacts followed by the negative impacts that were found based on the analysis of the results of the research.

POSITIVE IMPACTS

- Exposure

People can interact with other people around the world through social media networks which, empower them in many ways. Social Media becomes a platform where people can showcase their ideas or talents, learn new skills and acquire knowledge through social media.

- Finding friends

Social media is also able to connect people by using algorithms in a way that normally wouldn’t happen in the real world. The role of algorithms in filtering our results based on our history, location, interests and other details are explained in “The Relevance of Algorithm” by Tarleton Gillespie, the reading that was discussed in class. This reading speaks in detail of the “algorithmic identity” of a person and how this helps in filtering the results to provide us with the best suitable results based on our location, likes/ interests and our profile information. The high possibility of finding long lost friends has been pointed out as an important factor in expanding the social life of these young people.

- Mental Health

A large number of people mentioned feelings of motivation and inspiration while using social media. Using Facebook, WhatsApp and other apps help in increasing the friendship quality and network size.

- Interaction

Also, many people who are not comfortable talking face to face feel safe and less intimidated by chatting with a person online. The growth of mass self-communication, the communication that reaches a global audience through p2p networks and internet connection has been talked about in “The Rise of Network Society” by Manuel Castells.

NEGATIVE IMPACTS

On the flip side, social media has some negative impacts as well.

- Usage

Also, a large number of people used social networks when they are bored, as soon as they wake up in the morning or before sleeping with more or less no goals to achieve. Most of the people registered using social media for 1 to 5 hours daily. This increased time consumption by using social media may affect their productivity and cause addiction.

- Physical Interaction

Though social media is widely used for its socializing abilities, it is also criticized for reduced physical socializing capabilities. The impact of Social Media has changed the manner in which we see ourselves, the manner in which we see our personal relationships, plus it has also affected the manner in which we connect with our general surroundings. Most of the participants recorded having a huge number of friends online compared to the limited few who were their actual friends in real life. This may also be due to the fact that many of the youth accept strangers as on social media, making themselves prone to exposing their personal details to a group of strangers.

- Mental Health

Many young people complained of mental breakdowns. These people are also found to be obsessed with the likes and comments they receive on social media as they mentioned constantly checking and keeping track of the likes they received to account for their popularity. Many youngsters also confirmed how they compared themselves to others on social media by stalking their aesthetically perfect Instagram photos or staying up to date with their relationship status on Facebook. This causes an increase in unrealistic expectations, self-doubt as well as feelings of jealousy

- Physical Health

There are lots of unhealthy physical effects of social media usage. A large number of people indicated poor posture and eye strain as some of the physical impacts they experienced. One can get eyestrain from staring at screens for too long. Fatigue by staying up too late posting on social media was also an issue found among the youth using social media.

CONCLUSION

From this survey, I can conclude that most young people are aware of the risks and dangers of social media, yet they do not intend to quit these, as our lives are intertwined with it. Social Media usage, if constantly checked and kept under control, it can outweigh its negative impacts to make the social media platforms a better and effective means of communication. One of the ways of doing this can be by limiting the usage duration by having apps to track your usage and lock you out of your phones for a certain amount of time. Taking some breathing time away from these media can help bring back our conscience to the physical world and create a balance in our lives.

Observation of The NYPL Stephen A. Schwarzman Research Library

The Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, located on Fifth Avenue between Forty-Second and Fortieth Street, stands as a centerpiece for the New York Public Library. It is a grand marble building that has remained a spectacle since 1911. Few things have been changed in the library, beyond modern updates and fixes, and most people want it to stay that way. But what about what goes on inside the marble?

Are the librarians the same people that checked out the first books?

Have librarian practices remained the same?

Is information still circulated through the same stacks that were built in 1911?

Do people still use the research library?

What type of people actually participate in library offerings?

Just how old is this library?

To catch a glimpse at the answers to these questions, I spent a day observing researchers and patrons at the New York Public Library Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, as well as interviewing library staff.

Setting

I decided to spend most of my time in a smaller research room instead of the main Rose Reading Room for multiple reasons. First, tourists flock to the Rose Reading Room, and they are not the focus of my inquiries. Second, the Local History and Genealogy Milstein Division where I took up shop, allowed me to view researchers, librarians, and staff all at the same time. Third, this division of the library was broader than some of the other research rooms and as a result I would be able to observe a wider range of questions, requests, and interactions.

Observation

From the start I notice that everyone who enters the research room has one two reactions. They either straighten up and constantly check with the librarian visually to make sure they are not breaking any rules (similar to how people react to seeing a police officer), or they smile and say hello as if they feel welcomed. Both reactions indicate that librarians on title alone have a level of respect from the general public. It is for this reason that they have a certain code of ethics and an obligation to their community to keep the information in the library safe. It is also why diversity among library staff, and inclusion for all is so important in a library. As respected figures, librarians set a standard for others.

Staff & Diversity

It is not difficult to see that the New York Public Library places value on diversifying their staff. The Local History and Genealogy division (LHG) in particular represents varying races, sexes, languages, genders, ages, and sexual orientations. The library publicly puts valuable information into all types of people’s hands, which I believe is an effort to normalize the idea that information professionals can be anyone.

Interestingly, I also noticed that most of the librarians in LHG were male. In my personal experience it has often been that most librarians are women. Despite this, I noticed, unsurprisingly, that there was no change in how the librarians interacted with patrons or researchers, or how their work got done. Overall, based on the ALA Manual definition of diversity- “race, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, creed, color, religious background, national origin, language of origin or disability”, the NYPL has kept up with ethical and responsible hiring standards.

Patrons

If the librarians are the brain of the library, and the books are the lungs, the patrons are the heart. Without the people that wander the stacks looking for information, nothing would be read or investigated. The librarians would be out of job, and the books would be useless. It is for this reason that I found it interesting that not everyone has equal access to the library.

The key to everything NYPL has to offer is a library card. It is a simple plastic thing with a barcode number that can reveal a world of opportunity. Want to check out a book? Better grab your library card. What if you want to browse the internet for a bit? Got to use your library card. It seems the only thing you can do without a library card is stare out the window and enjoy the climate controlled building.

To get a library card you need two things: an address, and an ID with that address on it. For most people that come to the NYPL this isn’t an issue. Even if your ID has a different address on it, you can pull up a bill or a piece of mail with your name and place of residence on it and they’ll welcome you to the club.

For a smaller, but still very relevant group of visitors, however, having an address is not easy. According to the Coalition for the Homeless, there are 62,391 people without permanent homes in New York City. That is 62,391 people who cannot use the library to find jobs on the computer, or check out a book to develop marketable skills. This exclusion of a group of people that would benefit significantly from library services is definitely a flaw in the NYPL system.

Interview

After spending some time observing in LHG, I sat down with one of the librarians so that I could learn about the things I couldn’t see. Contrary to stereotypes, he had a demanding voice and stature and I felt compelled to listen to him.

Information Overload

One of the more important topics revolving around librarianship, in my opinion, is how these professionals handle data or information overload. Not long ago librarians often had to fight against having too little information available to them. With the internet, digitization of thousands and thousands of records and collections, as well as increased patron contributions, librarians have an overwhelming amount of resources. When asked about this, the LHG librarian explained that he had to learn how to research more effectively. Databases have helped narrow down search results, but he mostly relies on his own ability to filter out the extra stuff. He also mentioned that in the research libraries in particular, patrons use the online catalog and databases to find their own materials before bringing it to him for assistance. This means, however, that his job also now includes teaching patrons how to use the library website, its databases, catalog, and other little overly complicated bits.

With all of this new digital content and information floating along above our heads in the cloud, an important question is; Who owns it, and why do libraries have it? The librarian had a quick answer to this, which was if the library had to own everything it circulated, no one would know anything of importance. He pointed out a feature of LHG that was pretty popular with researchers; a file system of researcher-created records of families, places, and things. The library doesn’t necessarily own any of the findings in those files, but it keeps them and cares for them because it’s the library’s obligation to to do so.

Burnout

Naturally our conversation concerning piles and piles of information lead straight into my next question. Did he ever feel burnout? Was he ever tired of his job and did he ever feel like the work wasn’t worth the punishment? He had been quick to respond before, but was slower this time. Yes, he did sometimes feel the effects of burnout, but not in a way that made him feel like his work wasn’t worth it. Rather, he felt that sometimes the institution thought his contribution was less than what it was in reality, and that was the frustrating part, reasonably. I found this interesting considering I had previous overheard two librarians gossiping about how the people making important organizational decisions knew nothing about the system. The conclusion from this is that the NYPL administration may not fully consider the insight of those who work in the very trenches they are redesigning.

Politics, Neutrality & Librarianship

I managed to end my inquiry on the most difficult topic; Librarianship and neutrality. The librarian I spoke to had little trouble forming an opinion, ironically. He suggested that librarians can be neutral until there is a political or ideological thought that threatens the overall well-being of the library’s patrons or the collection. Generally, politics can’t play a part in researching a topic for someone, because that could limit what information you can give. Same goes for controversial ideas. He did mention at the end of our talk that he believes that it’s impossible to stifle your own beliefs completely, and that its the responsibility of the person to control how those beliefs come out.

Conclusion

As I learned about the ins and outs of the library during my observation and conversation, I found the answer to my biggest question. Despite being old on the outside, most of the inside of the library was young and new. The librarians were informed and up to date on the pressing matters of their profession. The staff was diverse and welcoming. The exclusion of some groups in the city needed some work, but I feel as if the library is aware of this issue and is working on solutions. Overall, the NYPL Stephen A. Schwarzman Building is blazing into 2020 as a leader of library practices.

References

Birdsall, William F. “A Political Economy of Librarianship?” Progressive Librarian, no. 18.

Cope, Jonathan. “Neoliberalism and Library & Information Science Using Karl Polanyi’s Fictitious Commodity as an Alternative to Neoliberal Conceptions of Information.” pp. 67–80.

Gehner, John. “Libraries, Low-Income People, and Social Exclusion.” Public Library Quarterly, vol. 29, 15 Mar. 2010, pp. 39–47., http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01616840903562976.

Nauratil, Marcia J. “The Alienated Librarian.” New Directions In Information Management, vol. 20, 1989.

Rosenzweig, Mark. “POLITICS AND ANTI-POLITICS IN LIBRARIANSHIP.” Progressive Librarian, no. 3, 1991.

Rosenzweig, Roy. “Scarcity or Abundance? Preserving the Past in a Digital Era.” The American Historical Review, vol. 108, no. 3, June 2003, pp. 735–762., doi:10.1086/529596.

Vinopal, Jennifer. “THE QUEST FOR DIVERSITY IN LIBRARY STAFFING: FROM AWARENESS TO ACTION.” In The Library With The Lead Pipe, 13 Jan. 2016.

Field Report: MoMA PS1 Printed Matter New York Art Book Fair

Moma PS1 is one of the oldest and largest nonprofit contemporary institutions in the United States. It regularly organized an event to promote the museum. In this fall, MoMa PS1 hosted the New York annual Book Fair — Printed Matter. The event was held at MoMA PS1 sprawling campus from September 21 to 22. Printed matter’s is one of the biggest book fair of each year, which is a leading international gathering of artists’ books, celebrating the full breadth of the art publishing community. This annual book fair event draws thousands of book lovers, collectors, artists, and art world professionals. This year is the fourteenth year for Printed Matter to present the NYC art book fair.

Before I went to the event, I had several questions in my mind, which requires me to find the answer.

- Why printed matters?

- What is the age range of people who go to the book fair?

- How the exhibitors profit from their issues?

- What is the reason for people choosing to issue printed books over digital books?

- How they define “Archive”?

Regardless of the various digital reading products in the market, such as Amazon Kindle, the population of reading printed books has been descending year by year. Even textbooks are gradually going paperless nowadays. Also, among the teenagers in the 21st century, fewer and fewer teenagers are willing to read printed books. On the one hand, the price of books is always high, which is not friendly to book-lovers. On the other hand, a printed book is harder to carry around than a simple reading tablet.

This year, the Printed Matter event held over 350 booths. It’s a spectacular parade of art, fashion, zines, culture, subculture, color, sound, food, and various performance. At first, this extravaganza made me feel a little overwhelmed because of the dazzling booths. It’s really hard to find the specific exhibitor, ranging from artist collectives to antiquarian booksellers, offering unique publications. In the place of the Fair, there were visitors from different age groups and with different skin colors, but people who purchased the issues, the works, and the books mostly looked older and more knowledgeable. Younger people or teenagers were more thinking of the book fair as a weekend entertained event.

After finishing browsing most of the booths, I entered a booth with name “The Classroom”. The name was attracted me to walk into the space since I wondered what I might learn from this so-called “The Classroom.” This space is presented by a dutch artist, Ruth van Beek. She walked around and elaborated on her thoughts behind her practice in “The Classroom” to the visitors. The exhibit was a dedicated space that provided reading, screening, informal lectures, and other activities by artists, writers and designers. The program highlighted exciting new releases at the Fair and fosters dialogue around important themes for contemporary art publishing and the broader community. ‘That foster dialogue around important themes for contemporary art publishing and the broader community.’ Ruth described bookmaking as an inverse to creating an exhibition. “Making a book is more democratic. They’re for everyone.” After the talk, one of the audience asked a question that I was about to ask, “Will you ever considered making a digital book?”. Then the response from Ruth really touched my heart. “No”, she replied, “It’s the tactility of the book object.”

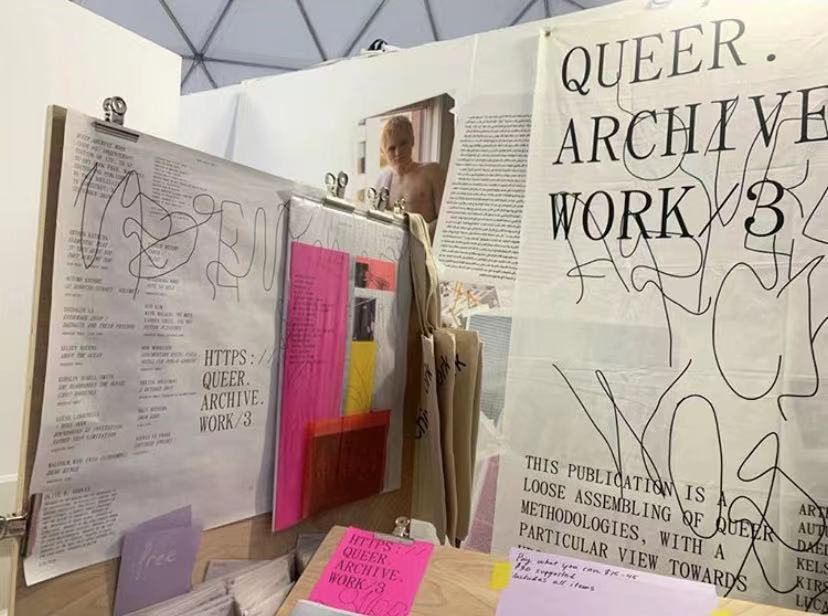

“Tactile” is a very appropriate word to describe the fair, and visitors were always encouraged to touch, interact and communicate with makers and exhibitors. After I walked out of “The Classroom”, my attention was attracted by a booth, “Queer, Archive, Work”, with slogans on the banner “This publication is a loose assembling of queer methodologies, with a particular view towards network culture, failure, and refutation.” The keywords, Queer and Archive, made me walk towards the booth. I asked the exhibitors Paul Sollellis who is also the co-publisher of this work, about how does he define “Archive” in his publishes from the view as freelance artists. He told me that archive is a process of gathering and collecting memories from different individuals then putting them together. Paul elaborated the issue he was selling on his booth to me that one package contains works from multiple Queer artists. There are journals, photographs, paintings and collages inside. Following his words, I asked him why he chose to do physical copies instead of a digital one. He gave me a short talk on the philosophy level by saying that this is all about the sense of existence and the weight of things. Everything has its own weight, you will know it only when you feel it. I remembered his face looked very serious, not like a seller who was trying to promote his product. I felt that he really believed that the meaning of existence is all about the feeling, or the “tactility”.

Paul’s definition of “Archive” reminds me that what make archive so significant to our lives is those archives are always meaningful to someone in the world. Like Archill says in his article, “however we define archives, they have no meaning outside the subjective experience of those individuals who, at a given moment, come to use them.” (Mbembe, 2002) Only the things we are doing contains meaning then there is the significance of existence. So is “Archive” and the printed books. Books have different meanings for different individuals. For Ruth, printed matters because of the facility of the book object. And for Paul, printed matters because the weight of the books is the proof of existence. Then I cannot help but think does printed matter to me and why. This is a question that I haven’t found out the answer.References:

References:

“Paul Soulellis, Editor – QUEER.ARCHIVE.WORK.” Printed Matter. Accessed November 3, 2019. https://www.printedmatter.org/catalog/53190/.

Mbembe, Achille. “The Power of the Archive and Its Limits.” Refiguring the Archive, 2002, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-0570-8_2.

Human Interaction With Audio Tour Guides

As technologies and their capabilities continue to be further developed every day, it is important to observe the ways in which they become integrated with existing forms of and institutions for different types of information. Museums are among the institutions that preserve information and provide the public with access to it, whether art, history, culture, etc.. According to Bates, information can be thought of as, “an objectively existing phenomenon in the universe, which is also constructed, stored, and acted upon by living beings in countless different subjective ways, each way distinctive to the individual animal having the experience” (Bates, 2006). Audio tour guides have been utilized in these spaces for a long time, serving to both provide information, and maintain the integrity of a silent shared space. However, the information that typically makes up the contents of audio tours follows the museum in a single direction, providing all consumers with the same information in the same progression. I see this as an opportunity to use UX design to improve upon an existing way in which information is transmitted in these spaces, and to make museum goer’s experiences more customized to their interests with the use of more specified user interface design and AI technologies.

To gain more of an understanding of other people’s experiences with audio tours, I conducted an interview with an avid museum goer, Suzanne. Suzanne, who loves consuming information about art and history in many different forms, explained to me that the main issues she has with following audio tours are: a.) an abundance of information, not all of which is interesting b.) a predetermined path through the museum space c.) a pre established pacing based on the length it takes to transfer the predetermined information. From her experience, her critiques can be broken down into dissatisfaction with the current “affordances” of the existing technology into issues of content, use of and transmission through space, and time (Sengers, 2000). For Suzanne, the perfect audio tour would be one in which she could autonomously control where in the museum she would like to be, which pieces she would like to hear information about, and the duration spent at each piece. This idealized vision is similar to what Senger calls the “AI Dream”, or the hope that, with the use of artificial intelligence, technology will be able to take on some human characteristics and make things much more enjoyable and personalized for the consumer, learning what they like and dislike through continuous use and data collection (Senger, 2000). However, when applying Bates’ definition of information as “some pattern of organization of matter and energy given meaning by a living being (or a component thereof)”, how does this conception allow for the “semiosis”, or linking of different components of information, with AI and other technologies that also take on life like characteristics (Bates, 2006)? It is a question for which the answer unfolds as these technologies are applied in real time.

For this reason, it is important to look at Yvonne Rogers’ detailed work in theoretical approaches to Human- Computer Interaction. Rogers highlights the fact that many people who are at the forefront of developing technologies, although they are aware of and wish to apply certain theories, often are competing with the race to be the next innovation, and do not always have the ability to develop a technology completely theoretically before it is demanded on the market (Rogers, 2004). Rogers concludes her in depth account of theories with a call for those developing technologies, particularly user interface design, to discuss and research which theories to apply and why. By doing such work, Rogers hopes a more universal language for developers will be created in order to be able to use and integrate these ideas into technology as it is being developed, instead of conceptualizing the effects after users are already engaging with it. After a theoretical framework is established, different decisions can be made to expand and refine the affordances of technologies in relation to what users need and want from said technologies (Rogers, 2004). I believe this is pivotal in order to create user interface designs that are useful and specified to the desires of the user. It is through interviews, like with Suzanne, that developers on all levels of technology can get a better understanding of what people want, where technology can improve, and inspiration for where new technologies should be aiming. In order to more fully develop how audio tours could be improved and what consumers are looking for, it would be very useful to conduct more interviews in museum spaces and work to create a version that takes into consideration all variables that are considered important, and make an audio experience that is catered specifically to each individual user. I hope to be able to continue exploring theoretical approaches to human computer interaction.

User Studies, Harm Reduction, and Queer Resilience

By Lillian Gooden

Looking at the Margins: Incorporating Harm Reduction Into Tech

Presented by Norman Shamas and Afsaneh Rigot of Article 19

Radical Networks Conference, October 2019

Hosted at Prime Produce, NYC

I attended the Radical Networks 2019 conference on a rainy October afternoon. This conference, which centers marginalized and oppressed groups, gathers artists, experimenters, and researchers, and invites them to exchange radical ideas on technology and telecommunications. Conference participants are radical thinkers who want to use technology to help their communities while resisting systems of control and surveillance.

The sessions that initially drew me to this conference were titled “Media Infrastructures and Racialized Territorial Formations: Perspectives from the South” and “Everything Has A Resonant Frequency: On Crystals, Networks, and Crystal Networks.”

These bore a relation to my term paper, which (as of now) seeks to explore the physical aspects and environmental tolls of the Web’s infrastructure. I came to hear the work of a researcher looking into issues of access for the largely indigenous populations in the warmer, tropical, most remote regions of Colombia in “Media Infrastructures.” I came to hear the insights of another researcher and journalist interested in the supply chain of the minerals that power our communications, from World War II-era radios to smartphones in “Resonant Frequency.”

Harm Reduction is Radical

But my attention was captivated by Shamas and Rigot’s presentation on harm reduction, entitled “Looking at the Margins.” To set the context, Norman Shamas began with a definition of harm reduction. Harm reduction consists of practices that ensure one’s survival and aim to minimize harm from certain activities, typically those that are illegal. With the aid of a tweet by @ReyBee10 (2018), they frame it as a term that was “was started by sex workers, queer & trans PoC, people who use drugs, people in the streets saving their own lives and all the intersections thereof—not by public health folks.”

They presented a few examples of community harm reduction practives such as needle exchanges and safer sex education. Central to the idea of harm reduction is the acceptance of pleasure being a normal part of human life. Taking an abstinence-only approach harms by withholding potentially life-saving information. Shamas and Rigot might argue that harm reduction is design justice in motion, as it involves those most affected by structures of domination design their own solutions (Costanza-Chock, 2015).

In addition, Shamas highlighted humanitarian assistance for migrants crossing the desert in the form of providing food and water. Those providing assistance, they said, act in awareness and opposition to structural oppression in that they believe that migrants crossing the border deserve to live. If we are invested in reducing harm, we must shun stigmatization and judgement and work to mitigate risks instead. Harm reduction is inherently radical.

Harm reduction in tech matters because we currently lack a way to bring in systemic support for people that are being harmed while engaging in certain activities—without stigmatizing them. The presenters brought up two case studies to demonstrate methods of designing harm reduction measures and show their effectiveness. My focus is on the first of the two.

Case Study: Queer Dating Apps in Hostile Societies

Afsaneh Rigot, the second presenter, introduced a case study involving queer dating apps in Egypt, Lebanon, and Iran. In all of these countries, queer people are targets of persecution by government officials and fellow citizens alike. Of course, criminalizing sexuality has never prevented queer people from seeking and enjoying love. They have endured despite the risk of arrest and abuse.

The team at Article 19 sought to learn about queer dating app users, their needs, and design harm reduction solutions around these needs. Taking a design justice approach, they worked with local groups in Egypt, Lebanon, and Iran to get a sense of the environment on the ground. As they embarked on their research, the team understood that “the full inclusion of people with direct lived experience of the conditions [they were] trying to change” was crucial, to use Costanza-Chock’s words from “Design Justice.”

User Interviews Yield Revelatory Findings

It was established early on that participants in these countries had no interest in quitting their dating apps despite the risks, so proposed solutions had to support continued app use. Rigot pointed out that elsewhere, trainings around risky issues tend to be prescriptive, talk down to users, and fail to meet them where they are. Proposed solutions produced by these sessions fail their users by misunderstanding them and their needs.

For example, the discussion around safety on queer dating apps typically centers on privacy and geolocation. It is often recommended that users disable this feature in order to protect themselves. This advice seems reasonable enough, doesn’t it?

However, in talking to queer communities in this study, Rigot and Shamas found that surprisingly, geolocation was one of the features that made users feel most secure when chatting with other GPS-located users on dating apps. Many respondents brought up that knowing that the person they were engaging with was someone who lived in their town made them feel safer!

This revelation underscores the importance of learning locally desired applications or service—one of the ethical guidelines for fieldwork laid out by PERCS at Elon University. It is crucial to tailor any solution that you are designing to the specific needs of your user, and to uncover those needs through dialogue and direct engagement.

The Article 19 team found that devoting energy to developing geolocation solutions would not have been the best use of their time and resources, especially as many users already employed tactics such as GPS spoofing to preserve their anonymity on queer dating apps. Instead, users expressed that they would find it beneficial to have legal resources embedded in the apps they use in the event that they found themselves a target of government surveillance or other abuse.

In their findings, the Article 19 team also identified a desire for app icon cloaking. Suspected “deviants” in the countries surveyed sometimes found their property, including the information on their phones, subject to search. A queer dating app discovered by a government official could be grounds for penal action. By cloaking their app icons, users might be able to keep themselves safe(r) by disguising, say, Grindr, as something so innocuous as a calendar or calculator app.

Perhaps this reality seems distant from a US perspective, as we live in a country where a queer person can legally adopt children, marry their beloved, and even run for president. However, the reality is that despite our tenuous legal protections, many queer Americans live in daily fear of persecution, discrimination, and violence. Solutions like the above can still be of use even to those who do not live in such overtly hostile environments. Designing solutions for the most marginalized in society will yield applications that can protect all users.

Works Referenced:

Costanza-Chock, Sasha. (2018). “Design Justice: Towards an Intersectional Feminist Framework for Design Theory and Practice.” Proceedings of the Design Research Society 2018. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3189696.

PERCS: The Program for Ethnographic Research & Community Studies. “The ethics of fieldwork.” Elon University. http://www.elon.edu/docs/e-web/org/percs/EthicsModuleforWeb.pdf.

ReyBee10. (2018, Oct 10). “#HarmReduction was started by sex workers, queer & trans PoC, people who use drugs, people in the streets saving their own lives and all the intersections thereof— not by public health folks….respect the origins and beware co-optation..to paraphrase @HarmReduction #HarmRed18” [Twitter post]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/ReyBee10/status/1052975455748452352.

Observation at The Met Fifth Avenue: How is the museum tour guide in including different kinds of visitors.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is the largest art museum in US and the third most visited art museum in the world. The main building in Manhattan’s Upper East Side in one of the world’s largest art galleries. As was posted on January 4, 2019 that 1,659,647 visitors were attracted to The Met Fifth Avenue and The Met Cloisters from May 10, 2018 to October 8, 2018. Based on the data from Wikipedia and MET official website, with such large number of visitors from all over the world, I began to curious how the visit guide provided by the museum service did well in considering different kinds of visitors.

According to what I learnt from Design Justice, the tour guide designed by MET should aim to ensure a more equitable distribution of the benefits and in this case, the museum tour guide should also consider non-English speakers, people with disabled, etc.

I went to The Met Fifth Avenue on 27th, Sep. to directly observe as a visitor and my goal was to see whether different kinds of visitors were guided friendly and effectively in visiting the museum. It was a cloudy afternoon with crowded visitors, and I waited for 10 minutes in line to get my ticket.

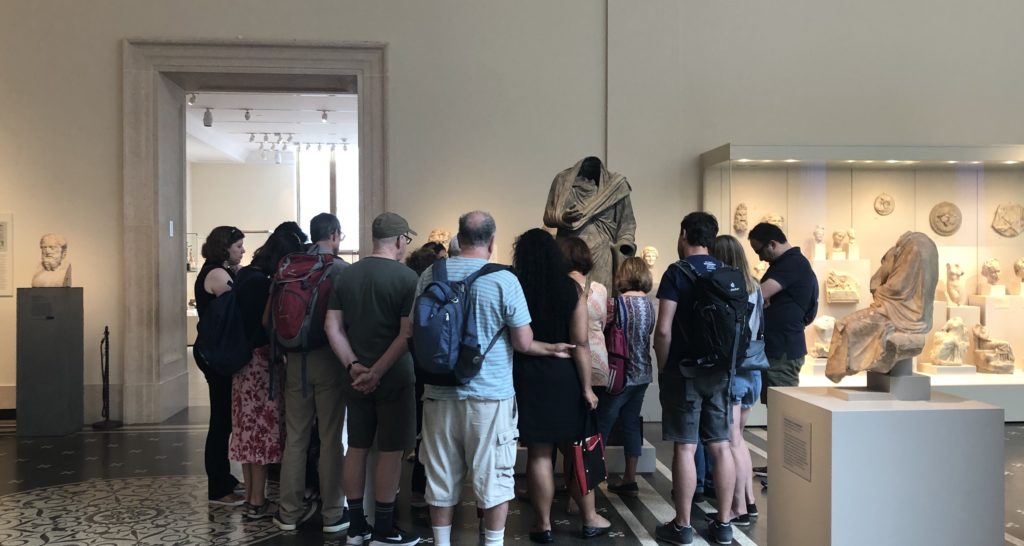

1 Manual Guide

I saw several cicerones surrounded by a small number of visitors. I joined them for free. Some visitors followed by cicerones carried backpacks and not seemed like locals. The good thing for getting a manual guide is that you could directly ask questions and get answers, especially for history or art fanatics who are always filled with questions.

But this method is not that feasible for visitors who prefer to get through the museum quickly and are not fluently English speakers. Since you are guided by a certain route and listening to deep explanations of the exhibits really takes time. In this period, I found some of visitors would only follow a few minutes then left the group to visit by themselves.

2 Audio Guide Rent Onsite

These days the most commonly used tour guide in museum is audio guide. At the museum lobby visitors could easily find the words “Audio Guide”, and the return place was also obvious to find. During my observation period, I found no more than 50% visitors were using audio guide and I guess it was because the audio guide in MET was not free, or some were not first-time visitors or some just preferred to quickly visit the whole museum without deep explanations.

2.1 Whether considering non-English speakers.

Yes. The audio guide provided by MET contains 10 different languages, which is especially considerable for foreign visitors. When I visited the museum, I found a lot of Asian visitors renting audio guide and listening to the guide frequently. It’s much effective for them to get the explanations in their mother language.

2.2 Whether considering visitors with disabilities.

During my observation period, I did not find disabled visitors. But I found some information on the MET website that the museum offered assistive listening devices and real-time captioning for visitors with hearing loss.

2.3 Whether considering aged visitors.

I found an old woman who seemed uneasy to input numbers into the audio guide to get the explanations. And some visitors seemed tired to hold the guide near their ears to listen all the time and they needed to find a place to sit or change to another hand to hold the guide. I think the interaction method between visitors and audio guides is not that friendly especially for aged visitors. Manually inputting numbers could waste time. Besides, the guide is not that easy and convenient while the MET is large, and most visitors would stay more than 2 hours.

I guess it’s better to add automatic induction function to the audio guide and visitors don’t need to input numbers themselves but only to answer yes or no to listen the guide. In addition, always holding the guide near ear to listen is not convenient. Why not provide earphones to aged visitors together with audio guide? Or support the visitors using their own earphones.

2.4 Whether considering visitors who prefer quickly visiting the whole museum.

I did find a visitor hanging the audio guide around her neck, but she didn’t use it during the whole process. And some only listened a few seconds then gave it up. I guess the contents provided in audio guide were too long and they only wanted to get a concise version. They came to the museum to get something new but not preferred to get that deep understanding towards a single exhibit. In that case, perhaps better to provide different versions for visitors to choose from. For instance, a quick 1-minute explanation together with a detailed 5-minute version.

3 The MET App

There is an App called The MET which also provides travel guides and even augmented reality function. The good thing is you could use it offline, while the bad thing is that you have to download it beforehand. How many visitors would take trouble to download an App to help them visit the museum? I guess better to develop a Web App for visitors who just want to visit temporarily.

During my observation period, I only saw a young woman using her iPhone to get the audio guide. Generally speaking, not a large number of visitors choose to get a guide on App. I believed one of the problems was not enough contents on App, compared to the audio guide you rent onsite.

Conclusion

In 2015, the MET did a thorough research on how to improve the audio guide and during the research they did find 40% visitors were foreigners and the importance of reducing the complexity of using audio guide. However, just like what Norman said, “The world is not neat and tidy and things not always work as planned.” All the tour guides provided by MET are roughly satisfied but still have space to improve. Perhaps reconsidering different visitors’ needs could help better the overall experience.

Reference

1 Wikipedia: Metropolitan Museum of Art: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art

2 Met Welcomes Nearly 7.4 Million Visitors in 2018:

https://www.metmuseum.org/press/news/2019/2018-calendar-year-attendance

3 Improving the Audio Guide: A Look at Our Visitors:

4 Norman, D. A. (1998). The Invisible Computer: Why Good Products Can Fail, the Personal Computer is So Complex, and Information Appliances are the Solution. MIT Press. Chapter 7: Being Analog http://www.jnd.org/dn.mss/being_analog.html.

5 Costanza-Chock, “Design Justice: Towards an Intersectional Feminist Framework for Design Theory and Practice”

Event Review: REcon 2019 UI/UX Conference in Bloomberg. LP

“REcon” is a yearly free conference for user researchers, and this event is an excellent opportunity to learn from industry leaders, share ideas, expand the connection, and discuss all things user research. The event was hosted on Oct. 5th and located at Bloomberg LLP. I was so excited to have this opportunity to join ‘REcon’ event. The event has all senior and above UX designers on-site to give speeches of sharing their experiences.

Audiences checked in around 8 am and had a short social time in the breakfast session. Most of the people I chatted with are from UI/UX design industry or have the intention to transfer into this industry. We exchanged our ideas about how we started to think about working as UI/UX designer. I met a guy who currently works as a UX researcher in Instagram with a very different background. He majored in gender studies when he was in college. He began to think of pursuing his career as a UX researcher when he worked on his graduate project. His topic was about porn culture and focused on human needs. He told me that when he worked on his project, he has done tons of interviews about why people watch porn. The result made him realize that the success of a product is all about meeting customers’ needs, and he found he would like to dig deeper into UX research field and design a product that matches customers’ needs. After having a small conversation with this interesting guy. The event was about to start.

The first guest speaker is Rachel Carpenter, the head of Design Strategy in Citi. She talked about why sometimes clients don’t care about the research and the result, but they still want researchers to do about it. She elaborated on what a researcher or designer should do when faces this situation. The first thing to do is to pitch the result and design ideas to the clients. During the process, give the clients multiple options to choose from, and interact with clients so that clients will have the sense of participant during the whole process. Thus, clients will have more interest in learning more about your research because they feel they are part of it. She also gave some suggestions and ideas about how to present your talent among your colleagues.

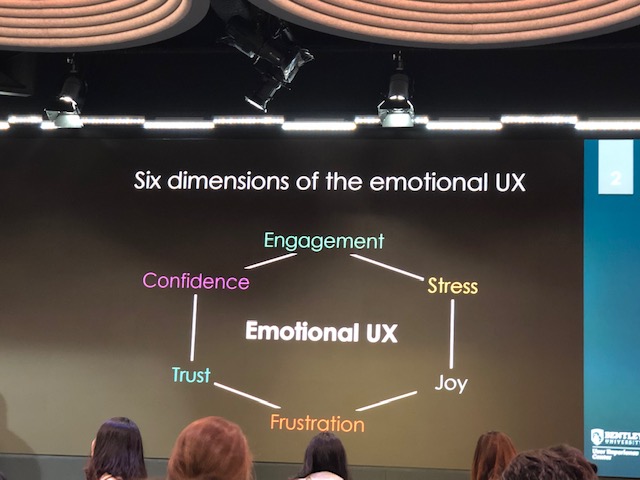

After Rachel, two more guest speakers who are from Bentley University, gave a speech about ‘A case study in measuring emotional engagement of customers using a virtual dressing room on an e-commerce website.’ They presented the research about users are most likely having the suspicious, ‘Is that really me?’ The key challenges they had were to accurately measure a potentially wide range of customer emotions, including engagement, joy, frustration, trust, surprise, and disgust. Their presentation shares the results from a case study that focused on measuring customer emotions while using different virtual dressing rooms using e-commerce websites. Biometric data from users, such as eye-tracking, facial expressions, and galvanic skin response (GSR), show a complete picture of the emotional customer experience which would otherwise be difficult to detect using analytics, market research, or traditional user research methods. This was a really interesting case study, which made me realize how widely the usability knowledge can practice in our world.

Next, we had Graham Marshall who from Zebra Technologies presents his talk about ‘Service design methodology for enterprise operations.’ He said that this methodology is often used to track the journey of a consumer through a thoughtfully designed retail environment or a citizen participating in a community service. This methodology is mainly used to analyze the dynamics of enterprise operations. At last, he stated that the practice of this methodology help to be able to communicate the interconnected complexities of the challenge and demonstrate where we might take it had been the most significant benefit of service design methodology.

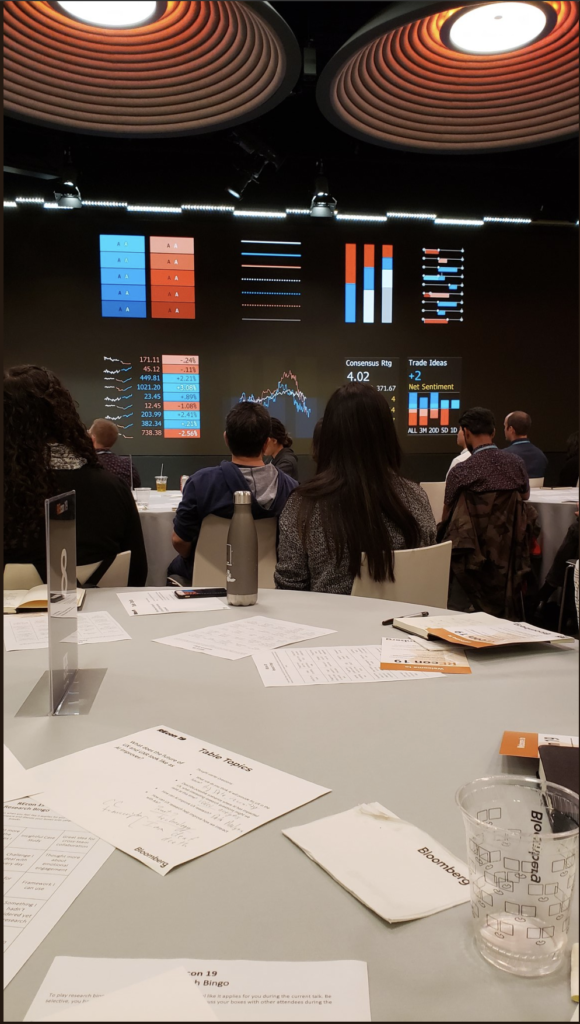

After Graham’s great speech, we had a lunch session in Bloomberg building. Staff from Bloomberg showed us around the building and the design department. Though Bloomberg is known as a finance company, the design department is more like an art corner which is full of creative decorates and structure. Bloomberg held a great lunch session, and they gave each table a topic to discuss during lunchtime to help people better interact and connect with each other. They even hand out some small games like ‘usability term bingo’ to make lunch more interesting.

In the afternoon, the first speech was presented by two Bloomberg user experience designer, Jaris Oshiro, and Hala Shih. The topic they talked about is color accessibility. They elaborated on what they would design for color vision deficiencies in the financial industry with their Bloomberg Terminal as an example. The presentation enlightens me that UI design should consider people from different groups, such as people with color vision deficiencies. Also, it reminded me of Norman’s design thinking regarding the culture constraints that ‘ Each culture has a set of allowable actions for social situation’ (Norman, 2015). If the culture is not able to be changed, then the change should be made on design. Every industry should not discriminate against those people having an abnormal part.

The last speech was presented by Natalie Connors and Tiffany walker, who is a director of design and strategy department and senior UX researcher JP Morgan Chase. Their speech was the one that I can relate most since they gave the idea about how to do the essential work in UX research. They shared some case they have done with Cognitive Walkthrough, Heuristic Evaluation and Usability Testing, which are the three topics that I am learning in this semester. Moreover, they also shared the tricks when they are doing the research, they will research about clients’ behavior at first. For better future service, it’s essential to know more about their clients’ preference. From Natalie’s talking, I was thinking of Wilson says ‘ the origins of human information study is seeking behavior research’ (Wilson, 2000).

In general, I had a great experience in this ‘REcon’ event. I met and talked to lots of interesting people. From the conversation with them, I realized I have a long way to go and feel like I have hidden passion in this industry. I believe what I have learned in this event would help me with my career in the future.

References:

Norman, Donald A. The Design of Everyday Things. MIT Press, 2013

Wilson, T. D. (2000). “Human Information behavior.” Informing science 3(2): 49-56