Observation of Frances Tavern Museum

Oct 23. 13:14-16:14

Introduction & Inspiration

I am always a museum fan but I was too shy to be there alone. I guess it might feel different when I visit sites of culture with friends when we exchange views. I have visited museums in locations with history of 2000 years as well as galleries of world famous art collections. This time, I was going to a place with longer history, than the country I am staying. I chose this site, mainly because I know just a little about American history and I want to experience, hoping that my pieces of knowledge could revive and connect with each other.

I visited the Fraunces Tavern Museum in Oct. 23, in a different manner. I observed with my eyes big and round. Usually I visited museums casually and I believe that I can come back another time with a fresh new mood and look. I tried to grow with the communication I had with friends whom I talked with during the visit. Sometimes, it is also valuable to try to talk with yourself, when you emerge yourself in front of historical occasions and sites.

I knew I love museums, but now I understand more of why, with some knowledge from Course 601: Foundation of information.

I See Different Types of Information Interaction

Come to the Real Site of Historical Places

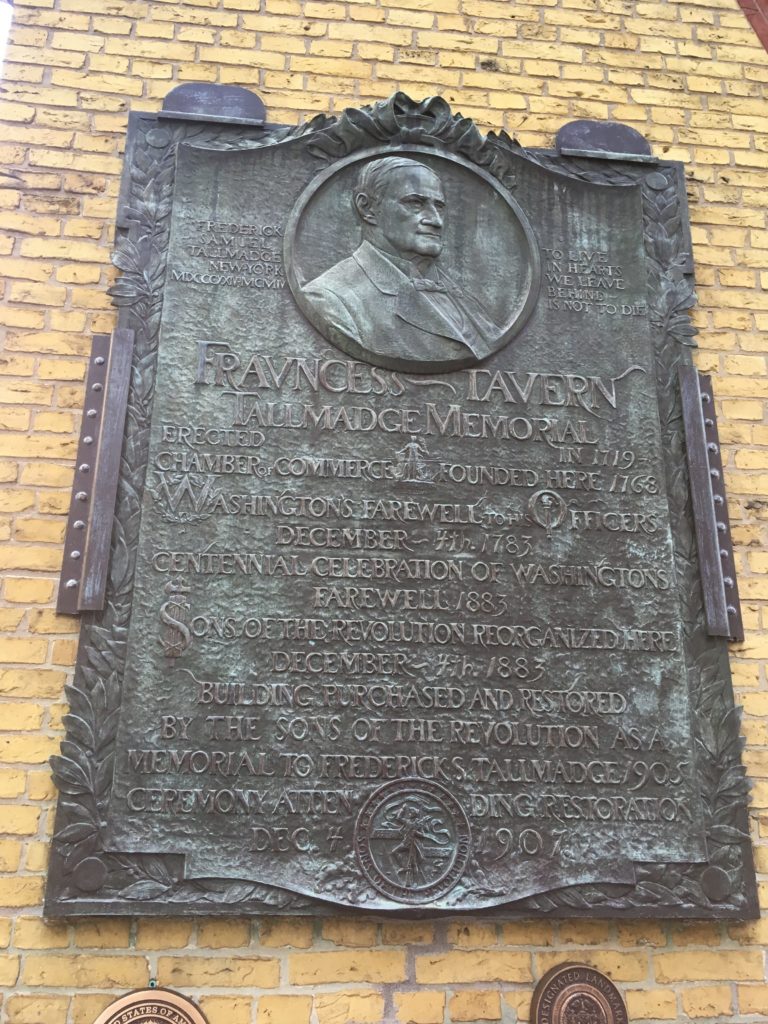

Read and Touch Tallmadge Memorial erected Dec.4, 1907

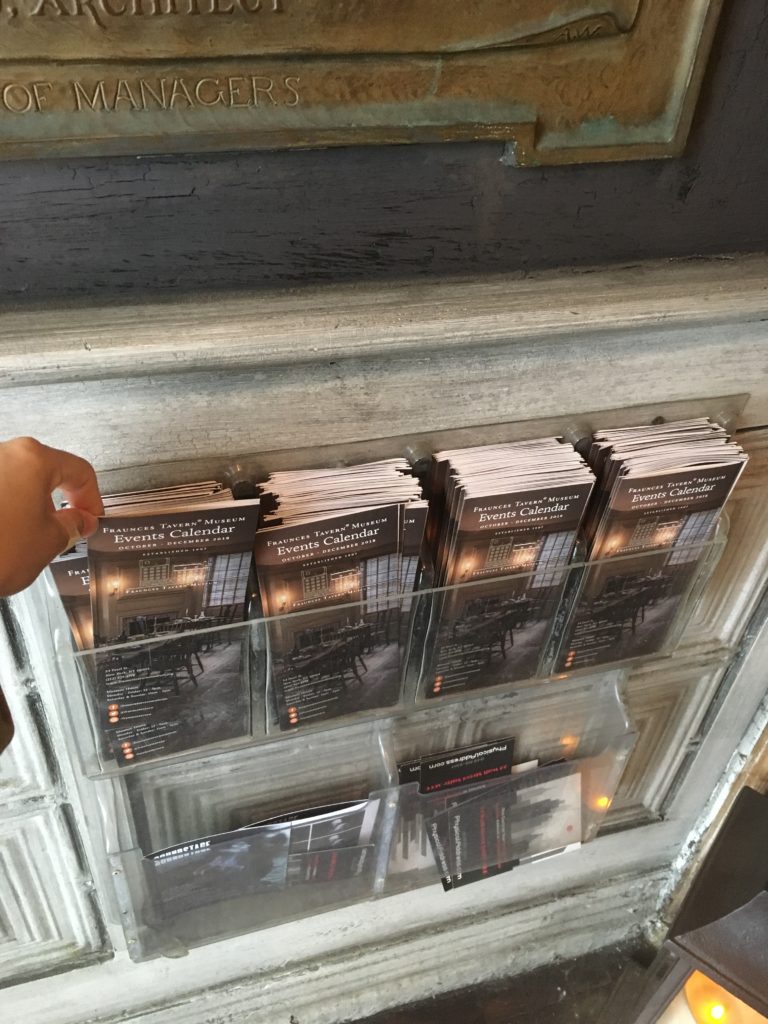

Read Event Calendar Brochure

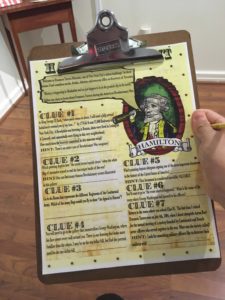

Play Scavenger Hunt

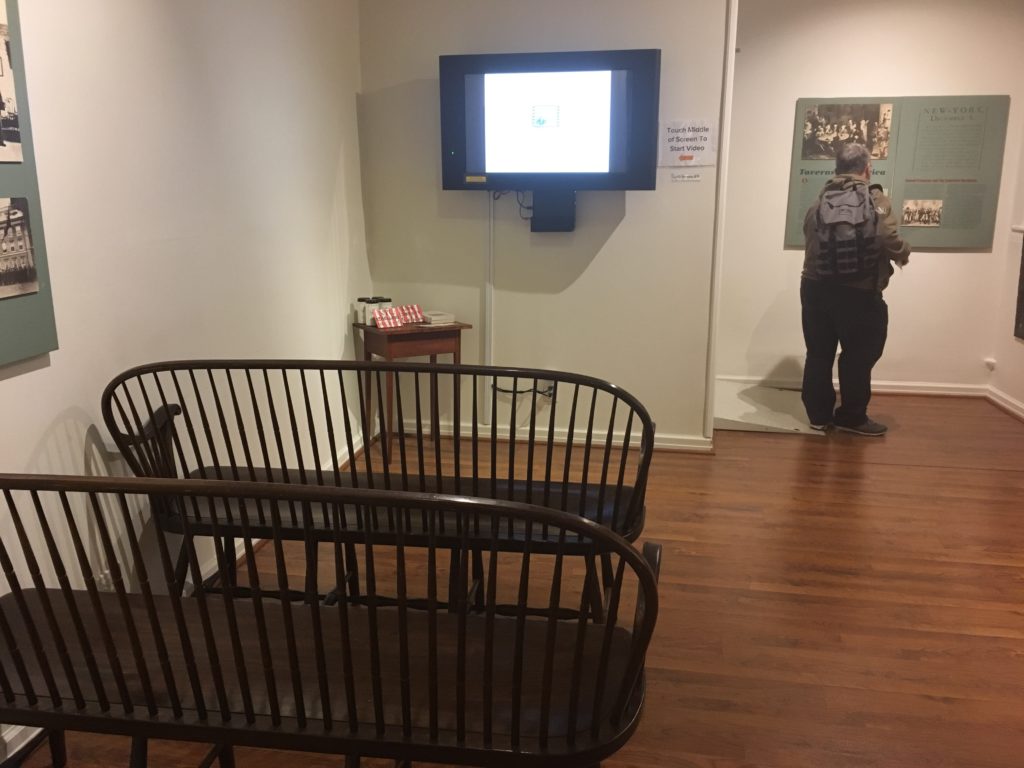

Watch Orientation Video

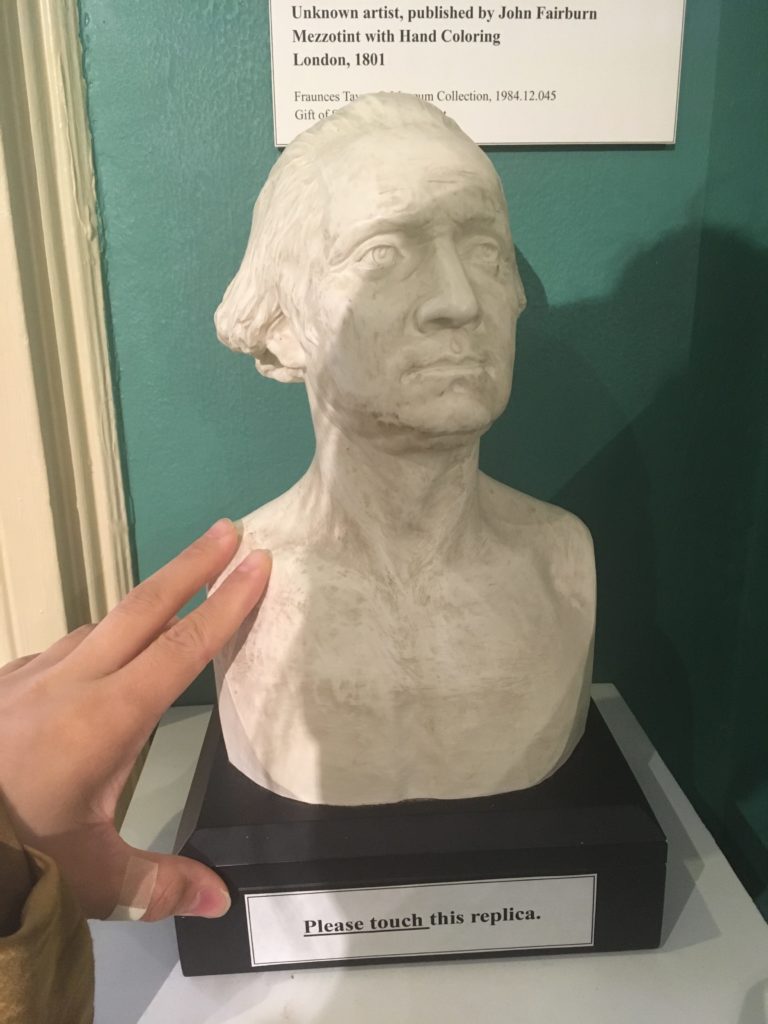

Touch Art and History

Take a Selfie with Mascot

Take a Selfie with Mascot

Smell the Merchandise-Tea

Decode Confidential

Decode Confidential

I Learnt Big Names and Great Events on Site|

Museum Collections

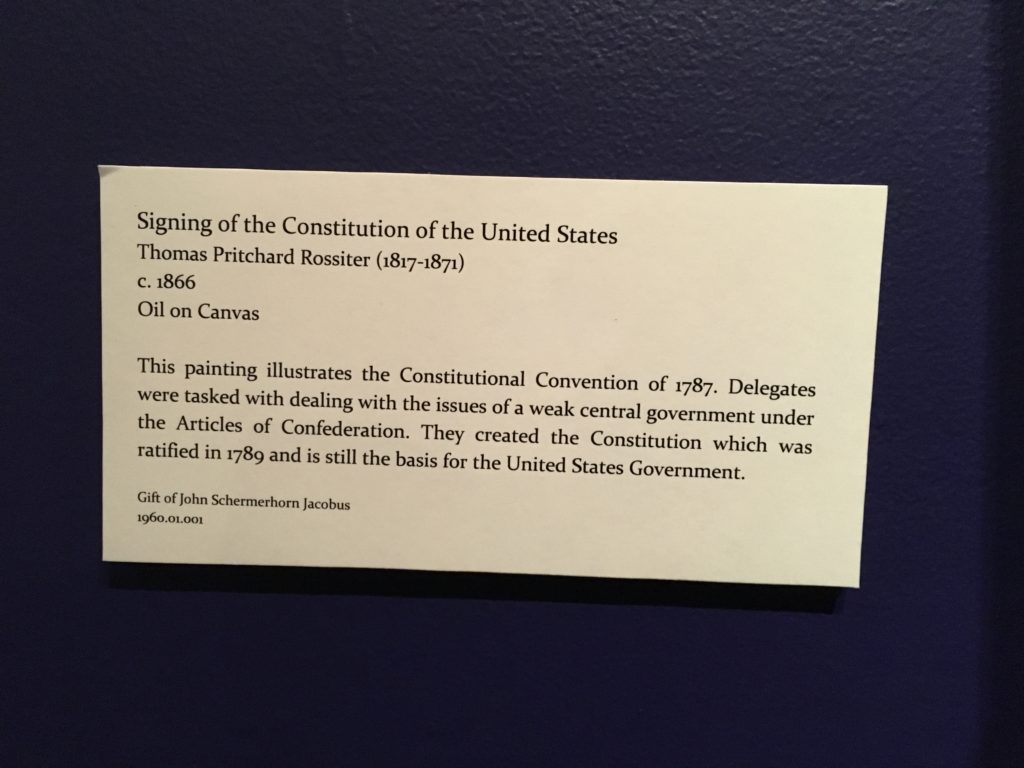

Fraunces Tavern Museum’s mission is to “preserve and interpret the history of the American Revolutionary era through public education”. On the history page of the museum online, we can find longer lines of history of Manhattan, than United States. If there is one collection to be the greatest moment, the next one would be the one: Signing of the Constitution of the United States.

It was in this room that President Washington took leave in Dec. 4, 1783, and the most emotional Memoirs of Colonel Benjamin Tallmadge, written in 1830 and now in the collection of Fraunces Tavern Museum.

“After the officers had taken a glass of wine General Washington said ‘I cannot come to each of you but shall feel obliged if each of you will come and take me by the hand.’ General Knox being nearest to him turned to the Commander-in-chief who, suffused in tears, was incapable of utterance but grasped his hand when they embraced each other in silence. In the same affectionate manner every officer in the room marched up and parted with his general in chief. Such a scene of sorrow and weeping I had never before witnessed and fondly hope I may never be called to witness again.”

The Long Room is preserved and no photo is allowed in this room. The best picture of that moment can be found in the engraving with hand coloring below.

Samuel Fraunces, as the “inn holder” of Frances Tavern, centered in the middle of commercial district, who owns business but also brings him politics connections.”On December 4, 1783, nine days after the last British soldiers left American soil, George Washington invited the officers of the Continental Army to join him in the Long Room of Fraunces Tavern so he could say farewell.” Later from May 1789 to Feburary 1790, Fraunces was hired, by Washington, as the newly elected President, chief steward in New York. “He was responsible for overseeing the operation of the house and a staff of twelve. ”

The “inn” is more than a living space, in 1768, chamber of commerce was founded here. It became actually the “center of politics”

Thoughts & Reflection

Museums to me, is another form of reading, in an interactive way, from multimedia sources. Compared to watching movie or documentaries, I love more of reading text and paragraph on a piece of paper material, such as a book. In this way, the reader has more rights to break and think twice at any pace. You can also take note, ask question or scan or search back and forth. A book after a reading process is never the same book it used to be, it became a product of both the writer and the reader.

My favorite categories of reading was biography and travel notes. These are based on true stories, it is supposed to. Publishing books is a way of telling a story in author’s tone. However, it is never the same, with a realtime and real space experience. Museums, are devoted to preserving the history and culture, in a different time, but real place.

Through the real touch of the original site, I feel the strong sense of politic hand in hand with finance. This museum was established in 1907. I wondered, will there be a museum of people in general, instead of politics. In Jensen’s words, there should be a shift from capitalism to liberal and pluralist, as well as democracy rather than corporate.

In Jenson’s article, 2008, “Library-Neutrality”, with open-minded applied to sciences, innovation increases; while with progressive applied to humanities, sometimes it is dangerous, well, “American revolutionary war arose from growing tensions between residents of Great Britain’s 13 North American colonies and the colonial government, which represented the British crown”. I feel that it maybe dangerous to British government at that time, but for American at this time, it is the opposite.

Reference

https://www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/american-revolution-history

http://www.frauncestavernmuseum.org/history/

While walking around the exhibition I noticed the following image at each stop posted on the floor. A graphic of a camera encouraging the patron to stand in that precise spot to take a photo, suggestively for Instagram, Twitter, or some other form of social media as the graphic was followed by “#museumofillusions”. This idea of

While walking around the exhibition I noticed the following image at each stop posted on the floor. A graphic of a camera encouraging the patron to stand in that precise spot to take a photo, suggestively for Instagram, Twitter, or some other form of social media as the graphic was followed by “#museumofillusions”. This idea of

As I mentioned I wish I would have attended the exhibition with a friend. As most of the pieces were intended for use by two or more people! The interactive component of the museum not only makes it more fun for patrons, but also speaks to the intentions of curators or exhibition designers. In our readings about user-centered research, focus has either been placed on the user as an individual or on the community. I would love to learn more about the relationships between users in an information environment. Seeing families and friends interact with one another at the museum was one of my biggest takeaways. One of the more simple illusions was a kaleidoscope with openings at both ends for people to look at one another through. I imagine the effect was much cooler when doing this activity with another person, as when I did it on my own the kaleidoscope did not produce the same effect. The most popular piece on view combines my early point about Instagram potential with social elements. Upstairs there is a room with furniture set up on its side, when people stand in this room they can take photos that create the illusion they are suspended.

As I mentioned I wish I would have attended the exhibition with a friend. As most of the pieces were intended for use by two or more people! The interactive component of the museum not only makes it more fun for patrons, but also speaks to the intentions of curators or exhibition designers. In our readings about user-centered research, focus has either been placed on the user as an individual or on the community. I would love to learn more about the relationships between users in an information environment. Seeing families and friends interact with one another at the museum was one of my biggest takeaways. One of the more simple illusions was a kaleidoscope with openings at both ends for people to look at one another through. I imagine the effect was much cooler when doing this activity with another person, as when I did it on my own the kaleidoscope did not produce the same effect. The most popular piece on view combines my early point about Instagram potential with social elements. Upstairs there is a room with furniture set up on its side, when people stand in this room they can take photos that create the illusion they are suspended.