On Thursday, October 17th, I attended several panels for the three-day conference Black Portraiture[s] V: Memory and the Archive Past. Present. Future. The stated purpose of the conference was to “explore the making of visual archives, the narratives they tell, and the parameters that define them as objects of study.” I listened to presentations and discussions about the particular difficulties of archiving when it comes to the records and materials of populations that have been historically oppressed, marginalized, and excluded from official archives.

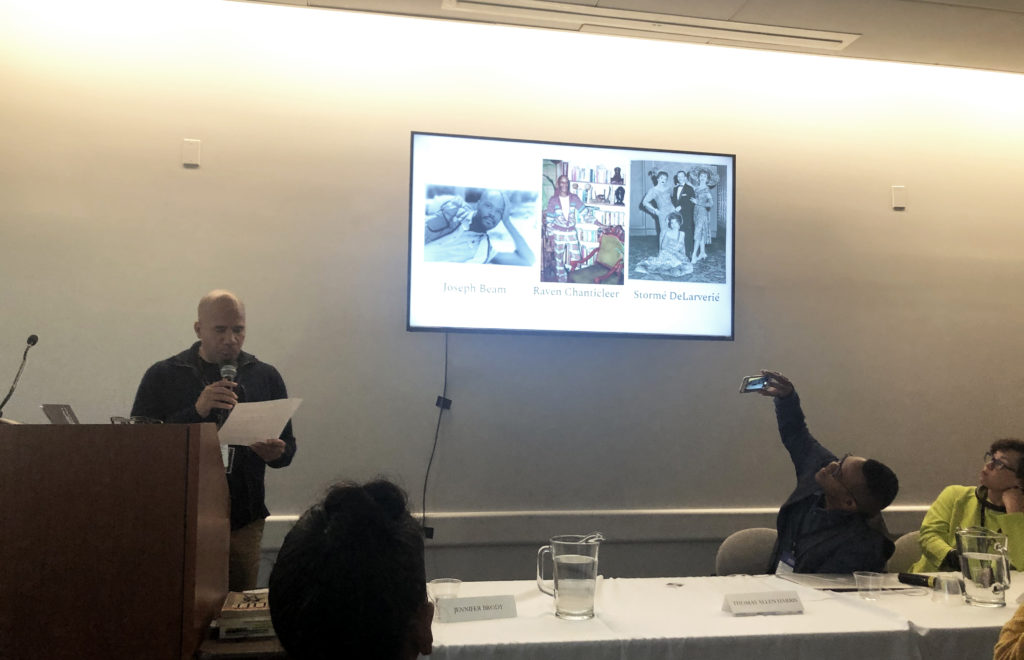

I was especially interested in the panel I went to titled “Representation Matters — The Evolving Black LGBTQ Archive,” featuring speakers Jennifer DeVere Brody, Thomas Allen Harris, and Steven Fullwood, with moderator Katina Parker. All black, queer professionals with backgrounds in the arts, their particular experiences and expertises lent to a vibrant discussion about intersectionality and the importance of identity in archiving.

Throughout their presentations, the speakers each emphasized the importance of maintaining a personal archive. When belonging to a community that has been suppressed from the “official” archive, especially when that community is a doubly-disadvantaged one like the black queer community, personal and “informal” archives are often the only way to preserve information about those communities. Something as simple as a family photo album can be a valuable resource in learning about the history of black queer people and communities, because when no one else is invested in the preservation and retelling of black queer stories, people in that community have to take charge of that preservation themselves.

The speakers presented many different examples of the way black queer people have been erased or understated in official histories: like Edmonia Lewis, a 19th-century sculptor brought up during Brody’s talk, “Out of the Future: A Black Queer-Femme Archive.” Lewis’ well-known aversion to dresses and probable affairs with women lead many to label her as a queer figure; but Wikipedia calls no attention to her preferred style of clothing, and simply describes her as having “never married.”

History is rife with these sorts of discrepancies, situations in which people’s identities aren’t fully acknowledged by formal archives. For people at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities—in this case race, sexuality, and sometimes gender—often the narrative prioritizes one identity over another. One might be a black historical figure, or a queer one, but rarely both. It’s in situations like these, Harris argued, that personal archives are most important. His presentation, “Queering the Family Album,” discussed how personal archives can be a powerful tool for families to better understand their pasts.

In black households in the U.S., Harris noted, homophobia and transphobia are common sentiments. But many family photo albums contain evidence of queer ancestors: an aunt who dressed like a man, a cousin in drag, a great-uncle who never married. These stories are suppressed on one level, but the physical evidence of a photograph is difficult to refute. In this way, personal, informal archives can provide an important link between the present generation and past ones; and, by extension, between future generations and the current one.

Harris’ discussion of the intersection of black and queer identity reminded me strongly of Sasha Costanza-Chock’s article “Design Justice” (2018). The importance of intersectionality is discussed in depth in Costanza-Chock’s article, where they argue that especially for people whose identities are marginalized on multiple levels, like those of race, gender, and sexuality, it’s important to recognize all of those identities as interlocking parts of the person. Without acknowledging the way that different identities interact with each other, one is left with an incomplete picture of an individual.

Personal archives, though, are often difficult to access specifically because they’re so informal. Fullwood’s talk, “Notes on Archival Visual Representations of Black LGBTQ Life,” touched on this challenge, discussing the way that so many personal archives are “collections doomed to the waste bin of history.” Whether it’s the destruction of records, an incomprehensible system of organization, or the inevitable damages of time, these personal archives are more often lost than they are preserved.

The themes of Fullwood’s presentation reminded me of several readings, including Michelle Caswell’s “‘The Archive’ is not an Archives” (2016) and Marcia J. Bates’ “Fundamental Forms of Information” (2006). Fullwood’s discussion of how personal archives are often poorly preserved speaks to Caswell’s point on the power of the archivist. Because information degrades over time, the decision of what gets preserved is left to whomever has access to the personal archives in question. Even if those records won’t be included in an official narrative, their continued existence is a far better fate than total destruction.

Even when information has degraded, Bates’ discussion of “embedded” information can illuminate why those damaged records can still have value. A water-stained photograph, for example, may speak not only to the great-grandmother in the picture, but also the flooded house her descendants lived in. In this way, personal records continue to accumulate and communicate information even beyond the “recorded” information, in Bates’ terminology, that was initially intended. This is why Fullwood advocates for people to maintain catalogues of their own archives—photos, documents, home video, and so on—so that they may still be interpreted and shared generations later, with all the added information that comes with time.

Also related to Caswell’s discussions of the power of archiving was Parker’s short presentation on the communicative potential of archives. She talked about the way archives create community and identity for a collective group of people: whether it’s of a society, as in official archives, or of a family or a group of friends, as in personal archives. In being excluded from archives, marginalized groups are excluded from their communities, which is what makes their own personal archiving so powerful. It’s a way to reclaim their narratives, their lives, from those who would rather their stories not be shared with the broader consciousness.

Parker emphasized that archiving is an important way to communicate across time and space; whether a photo is sent to friends hundreds of miles away or discovered in a dusty attic after decades, this communication acts as a touchstone for black queer people to connect with one another. As Caswell acknowledges that the archivist has power over how the story is told for future generations, Parker’s discussion presented the potential of having marginalized people as the archivists, the tellers of their own stories.

All of the speakers, in their discussions of intersectionality and power, time and space, came around to the same concept: that of legacy. Ultimately, being able to preserve and share personal archives is a way for marginalized groups to share their own legacies with the world. In times when official archives would exclude black queer stories, causing future generations of black queer people to doubt their own existence and history, the offering of an alternative archive allows the black queer legacy to live on.

References

Bates, M. J. (2006). Fundamental forms of information. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 57(8), 1033–1045. doi: 10.1002/asi.20369

Black Portraiture[s] V: Memory and the Archive: Past. Present. Future. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.blackportraitures.info/.

Caswell, M. (2016). ‘The Archive’ is Not An Archives: Acknowledging the Intellectual Contributions of Archival Studies. Reconstruction, 16(1).

Costanza-Chock, S. (2018). Design Justice: towards an intersectional feminist framework for design theory and practice. Proceedings of the Design Research Society 2018. doi: 10.21606/drs.2018.679

Edmonia Lewis. (2019, October 16). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmonia_Lewis.

Henderson, A. (2012, February 17). Edmonia ‘Wildfire’ Lewis: A black lesbian who sculpted freedom and independence. Retrieved from http://gayhistoryproject.epgn.com/historical-profiles/mary-edmonia-wildfire-lewis-a-black-lesbian-who-sculpted-freedom-and-independence-read-more-pgn-the-philadelphia-gay-news-phila-gay-news-philly-news-mary-edmonia-wi/.

Intersectionality. (2019, October 18). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intersectionality.

Jackson, N. (2010, November 12). Taking Care of Your Personal Archives. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2010/11/taking-care-of-your-personal-archives/66425/.