Recently, I went to the Bronx Museum’s “Useless: Machines for Dreaming, Thinking, and Seeing” exhibition. The exhibition was created to highlight the opposite purpose of machines. Rather than creating machines to produce labor or fulfill a practical duty, the exhibition featured artists all over the world who constructed or depicted useless machines “to praise inutility.” The exhibition was a direct “reaction to the materialistic values promoted by capitalist society.” The artists created a collection of machines to stir dreams, feelings, critical thinking, and ironies. I thought this exhibition was interesting because of its purpose to create something useless and meaningless out of machinery. In class, we talked a lot about machine learning, artificial intelligence and how we currently live in a machine culture. And according to Sengers, machines are embedded into every aspect of our lives:

“We are no longer…simply supplied by machines; we live in and through them. From our workplaces to our errands about town to our leisure time at home, human experience is to an unprecedented extent the experience of being interfaced with the machine, of imbibing its logic, of being surrounded by it and seeking it out…” (Sengers, 2000, p.5).

I thought that the exhibits at the museum highlighted what Sengers explained as the “shortcomings in technology.” The collection was a mixture of video, digital photographs, interactive sculptures and robotic machines behaving in curious ways. One exhibit by an artist named Fernando Sanchez Castillo displayed a video (pictured above) of a military robot that was originally designed to disarm explosives creating a painting in a slow, sarcastic manner. It was interesting how the artist inverted the function of the military robot by turning it into an artistic device. Technology is what we create it to be and as we rely on technology and machines to carry out dangerous or important tasks for us, the magnitude of its presence is felt even more when machines fail to (or are reprogrammed) complete the tasks we program it to do or they become useless. Transforming a machine so crucial as a bomb deactivating robot into a mere painting device changed the value of it as it was stripped of its former programmed task. This showed how machines can be used and recreated for other things than what it is originally meant for.

Unlike the artists, computer scientists are trained to identify these shortcomings and make solutions to those problems (Sengers, 2000, p.5). However, they are also blinded-sided by their myopic focus on improving machinery and not on the cultural context the machine is being made in (Sengers 2000). Thus, there can be unintended consequences of designing or creating a machine without discussing the need for it, the context it is being made in, and how it can be used in other ways if placed in a different environment.

I went to this particular exhibition with the intention to observe how visitors interact with the pieces within the space/ environment of the museum. But when I got to the museum, I found that visitors were not allowed to touch any of the art displays even though some of it incorporated interactive features for people to try out. I wanted to see if people were more inclined to go to the interactive exhibits which included displays of machines, video and robotic devices rather than the “non-hardware”/non-machinic ones such as photographs or drawings. Unsurprisingly, I found that people were more drawn towards the machine and robot displays. This brought to mind Norman’s Being Analog chapter, in which he explained why humans are inherently analog beings while technology and machines are created to be digital (2008).

According to Norman, “the world is not neat and tidy.” The world is naturally analog but with the advancement of technology and machines, people are forced to fit the world into digital models. Computers are logical and strict. Humans are unreliable and dramatic beings who are susceptible to making errors even if they are forced to behave in a machine-like way. Norman has described a world where technology destroys the mercurial essence of humans, but does not take into an account a world where both technology and humans are seamlessly integrated. Technology is no longer a separate entity of our world. AI and robots are becoming more human-like while humans are using advanced technology to enhance physical bodies and improve their health. In addition, AR devices are being created to integrate the real and the digital.

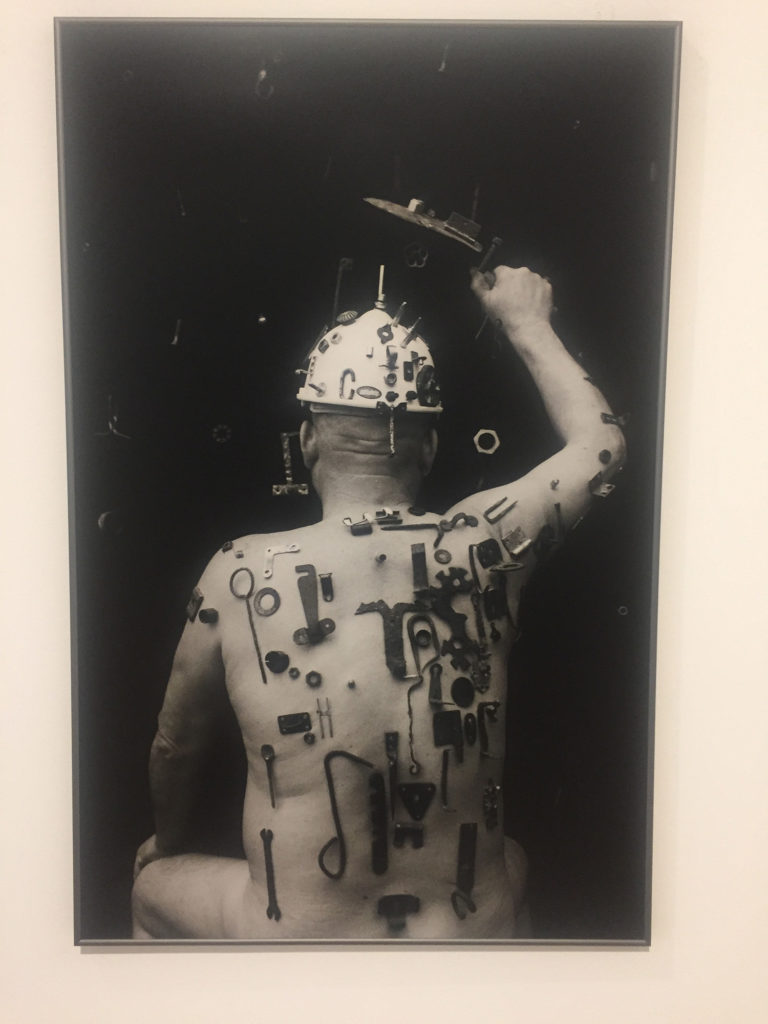

We are constantly interacting with machines and technology that someday maybe we will become as one–a concept that artist Algis Griškevičius depicted in his photographs at the museum. The photograph showed a nude man with numerous tools stuck and screwed into his body as if he was a living magnet or a hybrid. Within the scope of the exhibition’s theme of depicting useless machines, I found this photograph very telling of the future we may live in. The tools on the man’s body seemed useless, placed in a illogical or unhelpful way. It’s there because it can be; they are tools without purpose. Soon, perhaps we will live in a future world where technology is not only all around us, but just another extension of our bodies.

The exhibition’s concept of “praising inutility” reminded me of how technology cannot be studied separate from its cultural context in which it is made in. Even though the exhibition wanted to depict the uselessness of technology and machines, I realized by doing just that they created meaning out of the displays by making it art. Thus, the machines and collection of pieces were useful in an artistic setting of a museum but they, of course, will not be useful in a non-artistic setting.

References:

Sengers, Phoebe. “Practices for a machine culture: A case study of integrating cultural theory and artificial intelligence”. Surfaces, vol. 1, 2000, p. 2-58. www.pum.umontreal.ca/revues/surfaces

Norman, Don. “Being Analog”. The Invisible Computer, 2008. https://jnd.org/being_analog/