On October 4th, the Pratt Chapter of The American Library Association organized a tour of The Explorers Club, as well as a discussion with their Archivist and Curator of Research Collections, Lacey Flint. Headquartered at 46 East 70th Street since 1964, the Club occupies the former residence of Stephen C. Clark, an interesting figure among New York museums and history in his own right, and founder of the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. While Clark did not have a direct affiliation with The Explorers Club, his tastes in architecture and interior design have certainly shaped its surroundings.

As we ascended a hundred year old staircase and made our way past the mounted Polar Bear, it was clear we had entered a very unique kind of club. Seated before Ms. Flint, in a room lined by various framed expedition flags, our group was treated to a substantial information session about the history of the organization, and her professional responsibilities. Joined at times by other staff members who offered additional insights as they were going about their duties, we also had an opportunity for some Q&A with Ms. Flint following her presentation and throughout the tour.

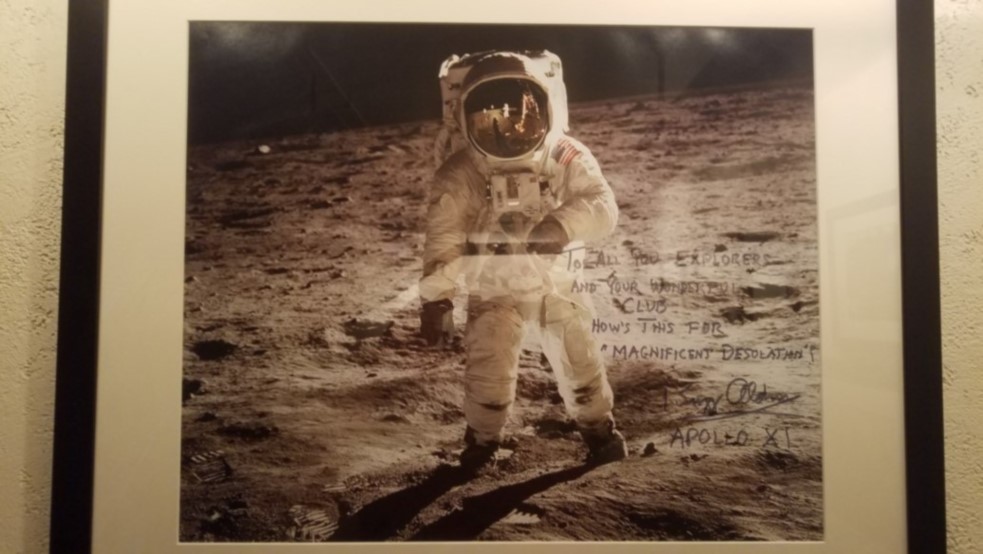

We learned that Explorers Club flags have been carried to the top of Mt. Everest, and the depths of the Marianas Trench, both the North & South Poles, as well as the surface of the Moon. Since 1918, over 200 flags have accompanied Club members on excursions all over the globe (occasionally beyond) and as I foresee myself eventually working within a museum or similar institution, one of my first questions for Ms. Flint was about the preservation of the flags and other items in her care. Despite being ensconced in the opulent trappings of Madison Avenue, the Club’s collection is curated under relatively austere means, and many of the retired and framed flags surrounding us were in need of conservation care and remounting under appropriate archival glass.

Progressing into what was previously the Clark family library, we were again reminded of the Club’s constant need for generating revenue, as they were in the midst of preparing the space for a ticketed event titled Tales from Dark Places. Though the bookshelves were partially obscured by large paintings of cave scenes (and rather ominous ones at that), it was easy enough to imagine a quiet read in the shadow of the fireplace’s massive mantel. What was less easy to imagine was how the family was able to navigate the assembled volumes, as Ms. Flint revealed to us a quirk of their personal cataloging. As opposed to author, title or even year of publication, we were told the books were sorted under broad generalities such as ‘things that fly’, a description that can encompass animals, aircraft and even celestial bodies.

This intriguing classification system brought to mind Finding Augusta, particularly the idea of “similarity” and the TSP. (Cooley, 2014) Viewing the library through the lens of the traveling salesman problem, I could imagine the parallels of trying to most efficiently find your way through the seemingly haphazard collection, while trying to gauge the similarity of subject matter as understood by someone else. Just as ‘Augusta’ could simultaneously describe many disparate things to different people, so did this Clark library lend itself to unique interpretations by those using it.

Reaching the highest level of The Explorers Club, our group became acquainted with the main showroom, and its large taxidermy collection. Despite the delicate nature of the artifacts, the room housing them is not climate controlled, nor have any countermeasures been implemented as of yet to address ultraviolet degradation from sunlight through the windows. (Though we were told the curtains are kept drawn most of the time) I had recently read “Fundamental Forms of Information” before the tour, and as we learned more about the mounted specimens, a passage immediately came to mind:

. . . structures previously associated with life recede back into their natural, inert forms. Trace information is that information that is degrading from being represented information (encoded or embodied) into being natural information only (neither encoded or embodied). Trace information includes the no-longer-used wasps’ nest, waste heaps, carrion, disintegrating ancient scrolls, and so on.

Bates (2006)

Even under the best of conditions, (and sadly the Club is far from being able to provide that) these artifacts and the information they contain, can not survive forever. As Bates explains, all organized elements eventually break down into basic patterns of matter and energy, and while organic decay is unfortunate, the loss of life of these animals in the first place is no small tragedy in itself. Though Ms. Flint assured the group that the particular examples on display were the result of scientific research, and not sport hunting, it is never easy to clearly discern the motivation of previous generations, and even a commemorative plaque within the room described the assorted animals as “trophies”.

Thinking back on this risk of complacency with questionable past cultural norms brought to mind a recent reading selection from Robert Jensen. His examination of “neutrality” in GLAM fields points out the potential dangers in accepting the status quo of an institution’s practices. (Jensen, 2006) Looking back on the tour with this additional perspective, I find myself conflicted over The Explorers Club’s taxidermy collection. While the specimens may still possess historic significance and cultural relevance, is their continued display a tacit approval of all the killing necessary for them to exist in the first place?

These shadows of the past can loom large in the ornate corners of the old Clark home, but moral ambiguity was not the exclusive takeaway of the day. Despite some questionable collection priorities, the Club does maintain its dedication to exploring the natural world, and one item in particular struck me as an eloquent overlap of information and exploration.

In this image, an inadvertent “selfie” of Neil Armstrong as captured in the reflection of Buzz Aldrin’s helmet, we see one of the only photographs of the first man to ever step foot on the Moon, and it was accidental! No satellite imaging, no high definition digital recording, not even a particularly captivating pose, just a man with some film in his camera snapping a photo of his coworker. Oh, and they just happen to be 200,000+ miles removed from the face of the Earth at the time. To be on the literal frontier of science, technology and human advancement, at the edge of the Abyss, and to capture it all with the click of a simple, mechanical shutter, it is a remarkable juxtaposition.

References

Bates, Marcia J. (2006). “Fundamental forms of information” Journal of the American Society for Information and Technology 57(8): 1033–1045. Retrieved from https://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/bates/articles/NatRep_info_11m_050514.html

Cooley, H. R. (2014). Finding Augusta: Habits of Mobility and Governance in the Digital Era. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/pratt/detail.action?docID=1524277

Jensen, Robert. (2006). “The myth of the neutral professional” in Questioning Library Neutrality, ed. A. Lewis. Library Juice, 89–96.

All photos taken by Ian Gregory 10-04-2019 at The Explorers Club https://explorers.org/