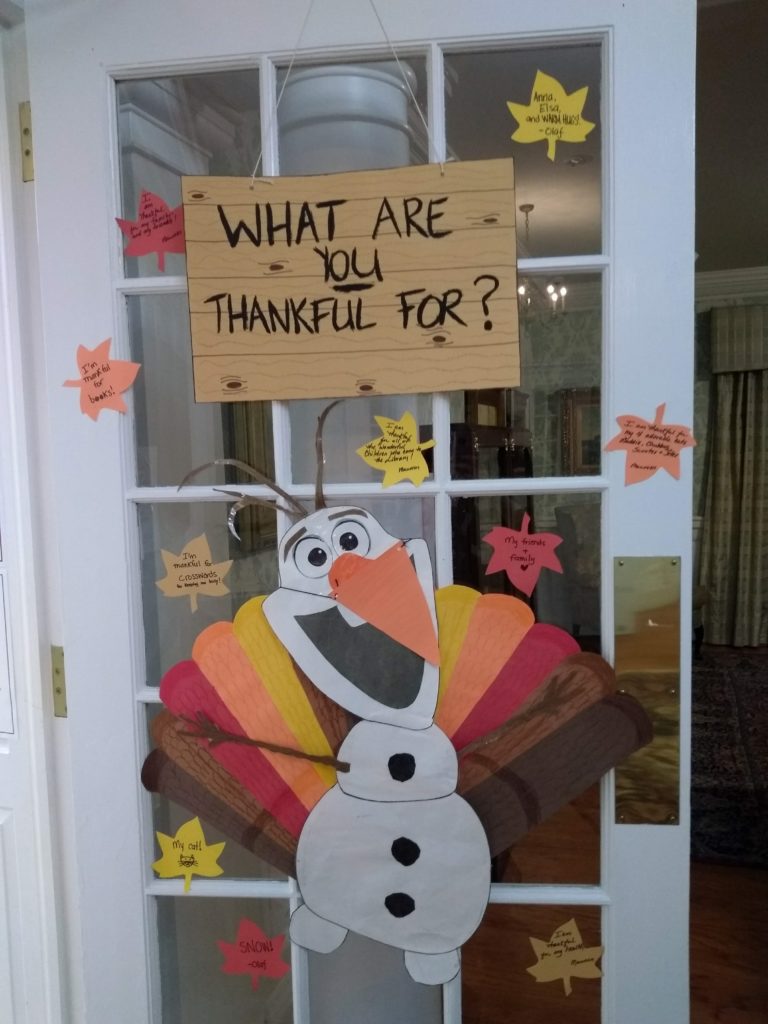

When I walked into the Eastchester Library children’s room in November, I was immediately welcomed by none other than Olaf, the snowman from Frozen. On the day of my visit, he was dressed as a turkey as part of a gratitude-themed Thanksgiving display on the inside of the opened front door (if you’re wondering, Olaf is thankful for Anna, Elsa, and warm hugs). Curious George, Yoda, Raggedy Ann, and others joined him to dance on the walls and welcome children into a space where everything is joyful, warm, and familiar. Many of the characters have been drawn or painted by the librarians themselves, whose extraordinary talents bring the characters alive.

Room by Room

Decorations like these are what make a children’s room just that: a space for children to feel at home. In fact, the three connected rooms that make up the children’s library are more residential-looking than they are institutional. The front room, through which you enter, contained the books for all the youngest readers (up to third grade) and the reference desk, as well as a small seating area near the picture books. Unfortunately, though, directly in front of me was a fireplace that stood right in the middle of the room across from the reference desk. It blocked the librarians’ view of what was happening in the seating area, which at the time included two toddlers jumping up and down on the couch. The librarian reprimanded them, but only after she was asked to do so by a concerned parent.

Through two wide doorways lay the second room, which housed nonfiction and fiction (third through fifth grade). This room also had a computer station with three computers that were blocked from the librarians’ view by a wall. The computers were unobtrusive and had no extra games or programs for the kids other than what can be accessed through the internet and ABCMouse. A quick peek at the nonfiction books revealed less than fifteen titles on technology as well. Clearly, then, digital literacy and digital information skills weren’t part of the library’s main educational focus.

The last room was a playroom containing large wooden tables, a LEGO area, and stuffed animals galore. Restricting the toys to this one space made sense for keeping the louder playing children separate from the others who wanted to read or ask questions of the librarians in the other room. The day that I visited, a cereal box stick puppet craft was held in the playroom on the big tables. The room was overcrowded and many children had to wait for others to finish before they could start on the craft. This was frustrating for the smaller children with little patience. Perhaps moving furniture, adding tables, or capping attendance would solve this problem: it would of course be better to do the former two, so as to not let the space constrain the library’s abilities to serve the community, but this may not be possible.

Suggestions for Improvement

Overall, I felt that the library’s set-up was efficient though old-fashioned in its deprioritizing of its digital aspects. Considering the great number of toddlers and elementary schoolers who use technology today, it’s important to teach them safe habits. However, this set-up does encourage stepping away from the screen, which is beneficial for children so young. My main suggestions for improving the library’s design would then be physical first: removing the fireplace in the center of the room (the librarians told me this hasn’t been done because of budget issues) and the wall blocking the librarians’ view of the computers would make it easier for the librarians to supervise what’s going on in all the different parts of the room if they’re at the reference desk.

Speaking of the reference desk, I found myself considering the movement to abolish the reference desk entirely (Luo, 2017). The desk can be seen from the hallway outside the children’s room and therefore easy to find. In the three hours of my observation, which were mostly after-school hours on a Tuesday, fifteen people came to ask questions, including one older man who was lost and needed help finding the adult history section. While I have read about this mostly in the context of academic libraries, I noticed that some of the shyer children had trouble approaching the monolithic desk to ask for help. However, it’s possible that roving reference paired with a smaller desk (as this was the main workstation for the librarians, it would be hard to eliminate altogether) may be less intimidating.

Though not perfect, I enjoyed my trip to the Eastchester Library Children’s Room in Westchester, NY. It may not have been the most modern of places, but it was clearly well loved by its patrons and I hope to return someday.

References:

Luo, Lili (2017). Models of Reference Services. In Linda C. Smith and Melinda Wong (Eds.), Reference and Information Services: An Introduction (155-178). Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.