I currently work as a nanny on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. My employers are white-collar workers, committed to their careers and to their children. Like many white-collar workers in NYC, they are not from New York, and their parents do not live in the city. In this role, I have participated in a hidden network of labor and information.

Person: Nanny

This job has revealed to me an entire system of labor that is hidden in many ways. As Downey (2014) discusses in the context of information and technology work, the work that nannies do is underrepresented by employers. It is common for nannies to work “off the books,” meaning that the income is not reported to the IRS and nannies and employers can avoid paying taxes. There are many reasons for nannies to want to remain hidden: immigration status, loss of public benefits, more take-home pay, etc. As a result, many nannies work outside of labor laws like minimum wage, overtime, and sick days.

Because there are few standards, there are a lot of nannies who are working for very little money. A nanny that I know, who is currently looking for work recently said to me, “a nanny’s worst enemy is another nanny,” describing the low salary offers that nannies are given. As Dwoskin, Whalen and Cabato (2019) discuss concerning content moderators in the Philippines, someone who is desperate may take a job with low pay because she needs the job. That makes it hard for other nannies to negotiate a better, commensurate salary. There are domestic workers unions and there is now a Domestic Workers Bill of Rights in NY State that might aid in this problem of labor exploitation. Personally, I do not know any nannies that are members of the unions or who bring up the bill of rights to their employers. In many cases, nannies would be uncomfortable to bring this up for fear of losing their job.

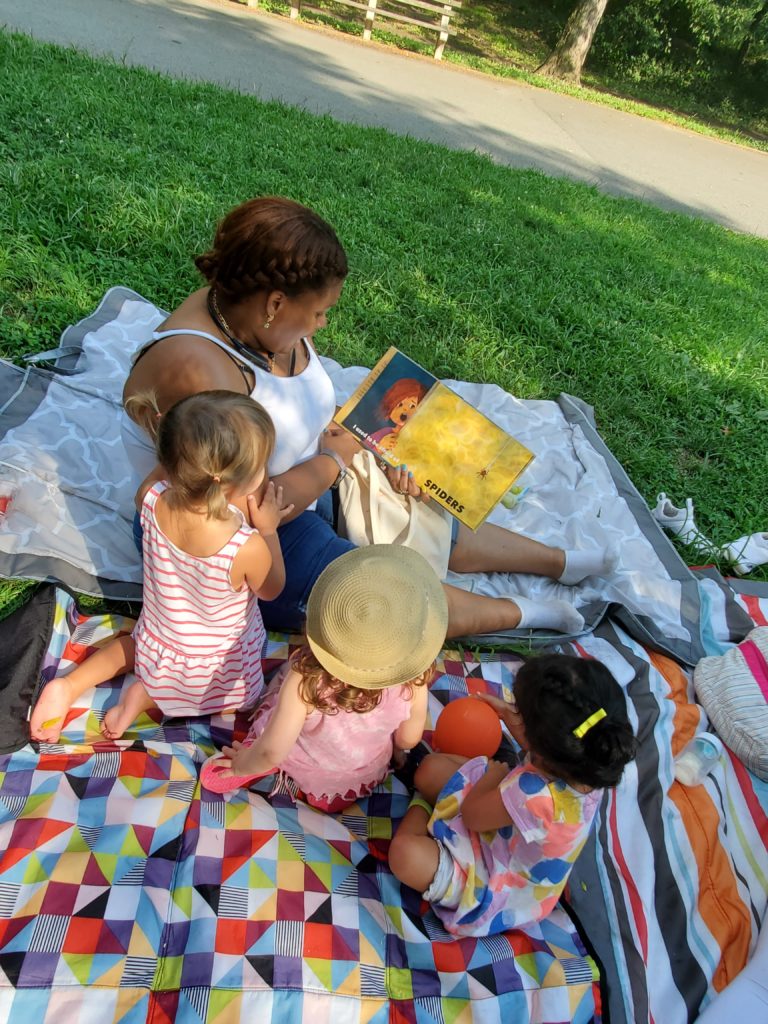

The work of nannies is also hidden because raising children is not typical work. Nannies do social, emotional, logistical, and educational labor in addition to physical labor. This work continues even when we are not physically at work.

Place: Household

The household is the physical workplace of a nanny. Working in the home immediately creates an intimate setting for the employee/employer relationship. I see my employers in their pajamas, I know their good and bad habits, etc. This intimacy brings a nanny into the family, which can be good and sometimes it is messy. A family member is happy to do favors, doesn’t mind when you are running late, and will answer your calls and messages after work hours. An employee, however, should be compensated for all the previously mentioned work, in addition to their salary.

In this dynamic, the white-collar workers are entrenched in their careers and outsource the labor of home and child care to their nannies. While nannies are ostensibly being paid to care for the children, they are also caring for the parents in the chores that they do and the emotional labor of maintaining the home as a familial space. Nannies are often responsible for deciding purchases, cooking meals, supplementing love and support, and constructing family.

Thing: Child-rearing knowledge

In the case of career nannies, as they approach retirement, they will have raised upwards of 20 children in their careers. With this experience, and perhaps the experience of raising their own children, nannies bring a wealth of knowledge to their jobs. For first-time parents, it is often the case that they have no clue where to start to be parents. Parenting is not something that we can study in school, and having children is obviously independent of one’s ability and knowledge of parenting. Sleep training, potty training, learning to read, etc. can be intimidating to parents, but are essential to the growth of the child, and with their experience, nannies often take on these responsibilities. Nannies construct household systems in addition to relaying knowledge and skills to their employers. These household systems include children’s daily routines, nutrition, sleeping schedules, and housekeeping maintenance.

Nannies bring traditional knowledge from their own cultures into the families that they work for. The nannies that work in my building are from all over the world, bringing with them their culture. From home remedies, to old wives’ tales, to cultural values, to folk songs and stories, this cultural knowledge is passed to the children, who then teach it to their parents. For non-native New Yorkers like my employers, they live away from their families and don’t have regular support or cultural knowledge from their parents.

A nanny’s knowledge of raising children is unmistakably valuable. However, this value is not reflected in the status, rights, salaries that nannies receive. This recalls the questions from the beginning of the semester from Bates (2016) and Buckland (1991): “what is information?” and “who gets to decide what information is?” Cultural knowledge and personal experience are not valued as information. Children-rearing is seen in American culture as women’s work, which is still undervalued in society. In addition, the emotional work and knowledge of raising children is difficult to measure, making it less valuable in the eyes of capital.

Resources:

Bates, M. J. (2006). Fundamental forms of information. Journal of the American Society for Information and Technology, 57(8), 1033-1045.

Buckland, M. (1991). Information as Thing. Journal of the American Society for Information Science. Jun1991, 42(5), 351-360.

Downey, G. J. (2014). Making media work: time, space, identity, and labor in the analysis of information and communication infrastructures. Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society. Cambridge: MIT Press, 141-165.

Dworskin, E., Whalen, J. & Cabato, R. (2019) Content moderators at YouTube, Facebook and Twitter see the worst of the web – and suffer silently. Washington Post, July 25, 2019.

Domestic Workers United. http://www.domesticworkersunited.org/index.php/en/

Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, New York State Department of Labor. https://labor.ny.gov/legal/domestic-workers-bill-of-rights.shtm