Much of the information people have been creating lately has been “born-digital,” meaning it was born on a computer or some other digital device. While this is convenient and certainly seems like a step in the right direction as far as access is concerned, it feels like we are losing something in the process. For things like news, posting directly to a website is great when one thinks about it. Newspapers are ridiculously wasteful. You buy one everyday and (usually) throw it out on the same day. I cannot think of a better candidate for digital reconstitution. However, the question we have to ask ourselves is will this news be readily available when it has become history, in fifty or a hundred years? Unfortunately, “that’s part of the danger of our digitized world — we don’t know how to store things for safe keeping hundreds of years into the future” (Heimbuch), and without this crucial information of how to preserve computer-generated content, it can be argued that we have no right to unload so much material onto the internet without backing it up with hardcopies.

The problem with digital information is not the fact that it is digital. It is the fact that it is ephemeral. Although it may last for several years in the digital realm, it will not last forever. While the same thing may be said of paper copies, the paper copies are not in a constant state of upheaval the way the digital world is. It seems convenient that fleeting information and fleeting attention spans have popped up at around the same time. Today, knowledge is quickly gotten and quickly gotten rid of. Perhaps it is because we are able to so easily find information online that we now take it for granted. Before computers allowed us to store everything we could think of, a lot like Bush’s “memex,” we had a bit more respect for tactile information. Now, the more advanced computers become, the more of a throw away lifestyle we find ourselves accepting. We keep our phones for a maximum of two years and our laptops for about three to five years. We have come to almost revel in our excrement and we do it with a smile.

Derrida says it best in his book, Archive Fever: “What is no longer archived in the same way is no longer lived in the same way” (18). Because information has stopped being truly saved for future generations, we no longer see it as an important element of our lives.

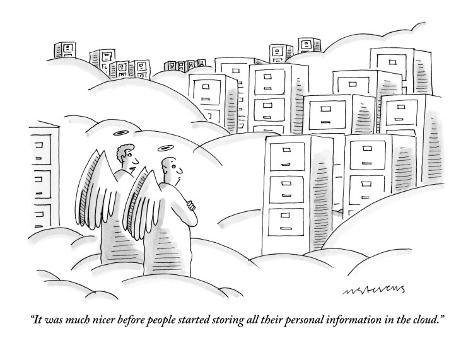

In a way, archiving has become more about the process and less about the result. In other words, how we archive has become more important than what we archive. How do we archive? Facebook, Twitter, Flickr, etc. What do we archive? Anything that is on our minds at any given time. This can get rather tedious and frankly boring. Seneca’s idea that, “it does not matter how many books you have, but how good they are,” is partially true (qtd. in Battles 9). We throw most anything into the “universal” Archive by posting things on the internet. But we do this without realizing we are adding to the Archive. Obviously some of the things added to the internet do not necessarily have to be saved for others to read in the future. It is not paramount that everything floating around the World Wide Web always be readily available. That goes for information not created digitally as well. Still, by making all information digital, we have set up a system through which we will haunt people long after we are dead with information that was never meant to be eternal. If you delete your Facebook account, all the information is still there and will always be there. If you save a Word document, you can delete it but they do not make it easy. With so much stuff and no real way to weed all of it, “instant info can make us a whole new breed of hoarder,” Heimbuch says in her article, “7 Major Ways We’re Digitizing Our World, and 3 Reasons We Still Want Hardcopies.” She contends that because of all of the information at hand, people feel compelled to absorb as much as they possibly can.

While the idea of people wanting to learn is commendable, it appears to be trending, hip knowledge that everyone is most jacked into, such as the latest gadget, which will become obsolete in a few years. Richer, more fruitful knowledge is usually passed over in favor of Skynet’s newest toy. But we should never forget: The T-1000 was not user compatible.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fjsSr3z5nVk

Works Cited

Battles, Matthew. Library: An Unquiet History. New York: W.W. Norton. 2003. Print