The New York Public Library’s palatial main branch is famed for its lionized gates to knowledge, and thousands of known and unknown scholars, artists, and autodidacts have used this space throughout its 100+ year history. The library functions not only as a research facility (where a full liberal arts education is available for free), but also as a fine art museum with galleries, murals, statues, architecture, and a tree lined portico. This is the ultimate library. It broadens the spectrum of what a library can be while maintaining what a library has always been.

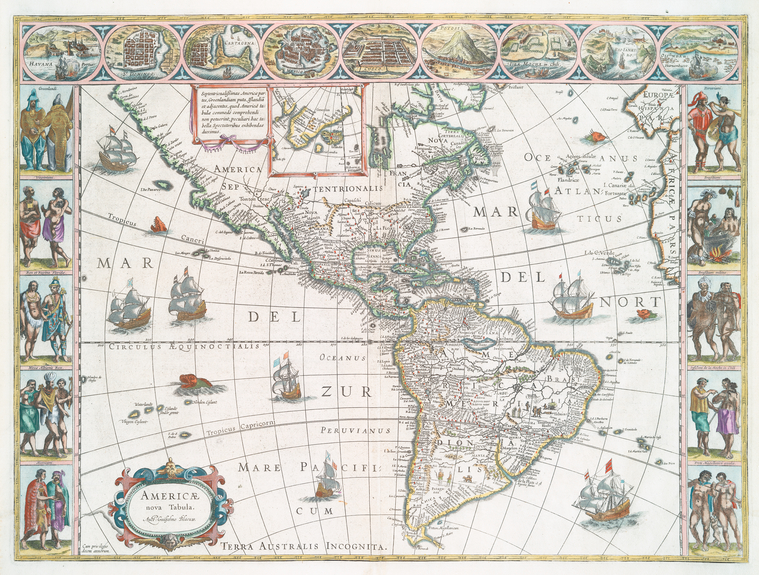

There are a variety of divisions within the library based on their subject (i.e. Periodicals, Prints & Photography, Rare Books & Manuscripts, Jewish Studies etc.); given the brevity of this article I will be observing only one: the Map Division, located on the northeast corner of the first floor. Their holdings include more than 433,000 sheet maps, over 20,000 books and atlases, all ranging from the 15th to 21st centuries. They have six computer workstations that allow access to Google Earth, Digital Sanborn Maps:1867-1970, Oasis NYC: community maps of New York City, and, as always, the NYPL classic catalog. Their reading room has twenty-eight chairs that surround three oak tables that are original furniture from the building’s inception (1911). In the reading room there are approximately 1900 open stack books for self referencing (using Library of Congress classification), twelve antiquarian maps along the walls, three sizable globes on stands, one gargantuan 45lbs. atlas of earth, and an enclosed map exhibit. Wi-Fi is provided and personal laptops are welcomed.

My observation is based on five visits, each an hour long, with casual interactions among the staff. The reading room is quiet and has a studious aura; the age range is diverse; within those seated most are using electronics, some are reading with laptops, and a few are reading & writing without gadgetry. Seating can be scarce as the famous Rose main reading room is closed, therefore, a whole table is designated for those referencing the map collection, for many of the maps are large and the atlases hefty. Tourist trickle through the room regularly, basking in the Beux Arts decor, taking photos, looking at globes, occasionally flipping through the open stacks, but the gargantuan atlas receives regular attention. However, there is a zoological feel to the tourist amusing themselves while patrons study; I overheard someone ask the reference desk why there were so many people here, presumably they could do all this work from home, the librarian obliquely responded: “they have their reasons.”

The reference desk is stationed by one librarian at a time, with new shifts beginning every two hours, and their demeanor exudes patience along with a nuanced knowledge of the collection. The librarians have seven avenues of patron relations: email, telephone, written, reference, consultation, direction, and instruction. The first three are usually a sort reference work, but sometimes an appointment is made for consultation, which can be an in-depth assistance and advising on research, or arranging a class visit with instructors and deciding on content. On one occasion I saw a class of 15 undergraduates led to the back with a stack of maps awaiting them. I also noticed in a historical atlas of New York acknowledgments given to the map division for its cartographic consultation. Direction is on the opposite side of the spectrum and far more common, as it directs people to the restrooms, power outlets, computer labs, or a specific location in Midtown. Instruction can consists of catalog usage, workstation navigation, or simply applying for a library card. These seven avenues are the librarians realm of service, all of which is done with the utmost patience and professionalism.

The variety of readers and their purpose is broad: students working on a project, geologist, real estate developers, insurance companies, lawyers, construction companies, map enthusiasts, fiction authors, scholars, and grandparents showing grandchildren their old neighborhood.

The table reserved for patrons reading from the collection is left empty when not in use. Prior to the internet, the map division would average 30 readers daily, but now it has dropped to an average 10, and it lowers slightly during the summer and winter months. The variety of readers and their purpose is broad: students working on a project, geologist, real estate developers, insurance companies, lawyers, construction companies, map enthusiasts, fiction authors, scholars, and grandparents showing grandchildren their old neighborhood. Occasionally, a gracious reader will leave a copy of their published work, but sometimes they speak in detail about their research and it’s always fascinating. This reserved table is one of three, and yet its significance is notable; an aura emanates from it, or perhaps it is simply in better condition.

Some of the older maps show methods of preservation, such as being enclosed in clear plastic (mylar), or backed my canvass (muslin), but sometimes they use facsimiles instead of the original because of its fragile state. The NYPL does have a conservation department, but some paper is acidic and beyond repair; digitization is the another method to for long-term use. Although, in one instance a researcher insisted on the original and was accommodated.

There are two catalogs that are used in tandem: one is a physical nine volume book call GK Hall, which is essentially the original card catalog that dates back to the Astor/Lenox libraries (now known as the Public Theatre & Fricke Museum) and catalogs up to 1978; after 1978 the catalog is online, but here’s the rub: only some of GK Hall material is online, so both catalogs are needed to reference the entire collection. The best of both worlds.

CONCLUSION: the librarians are patient, helpful, and consistent. The space is studious despite the flow of tourism, random a-socialism, and other spontaneous events. The collection is exhaustive and fully available to the public. Truly a gem of New York City.