The North Jersey History and Genealogy Center, which happens to be a part of the Morristown Public Library in Morristown, New Jersey houses multitudinous records of people not just from Northern New Jersey but from all over the state as well. Many of the documents range in date from around the late 1800’s to the 1920’s, although there are a vast amount of records that go back even further than that. James Lewis, the head of the Genealogy Center says that they are lucky to have a humidity and temperature controlled vault (which uses halon gas) because very few public libraries have enough funding for such technology. Within the vault there are an assortment of documents, including many now-defunct New Jersey newspapers such as the Democratic Banner, Jerseyman, and Iron Era. They also have a digital lab, which is extremely rare for a New Jersey pubic library. However, these nuances only scratch the surface of what the NJHGC has to offer.

Many people have heard of Tammany Hall and/or Boss Tweed, especially if you have seen the movie Gangs of New York, in which the historical figure has a prominent role. At the time of this “corrupt pol’s” reign, political cartoonist Thomas Nast was skewering him in Harper’s Weekly. Nast’s other claim to fame was “inventing” the version of Santa Claus we have come to know today, with his big, bushy beard and rosy cheeks. Although Nast was not originally from Morristown, he lived there for quite some time and raised his children in the New Jersey Town. The Genealogy Center owns a copious amount of Nast’s original artwork, as well as a large, original painting by him of Horace Greeley, the newspaper magnate, whom he also was not fond of. Another notable artist that the Genealogy Center has collections of is A.B. Frost, who is famous for illustrating the Uncle Remus and Brer Rabbit books by Joel Chandler Harris, although, as Joan M. Schwartz and Terry Cook would say, the Thomas Nast collection is clearly the “privileged” one. On the other hand, one wonders if the Nast records were consciously given precedence over the Frost ones, or if it simply comes down to what has been preserved from the beginning and what is available.

Some things are painstakingly documented, archived, and preserved. Other things are seen as not important enough to even remember. Some things haunt us forever and stay with us, which, according to Jacques Derrida, is an archive in itself. Despite the fact that the Genealogy Center is bright and welcoming, there is a dark crevice lying within its vaults.

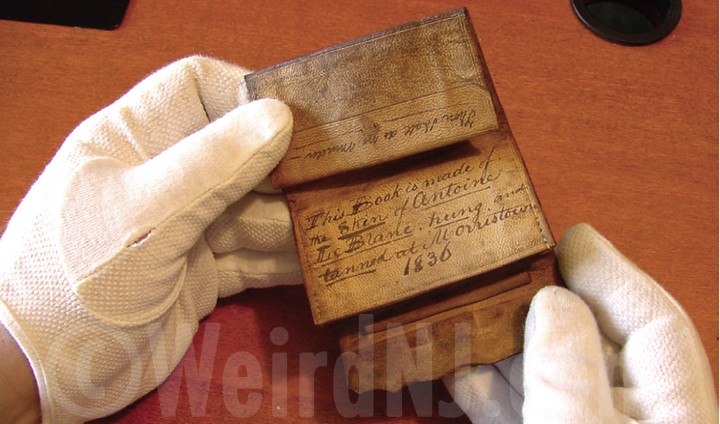

In 1833, there was a French immigrant named Antoine Leblanc, who worked on a family farm in Morristown for only a few weeks after having just arrived in the country. Feeling that he was unappreciated and underpaid (as in not at all), he decided to kill the couple and their servant. After he was caught for his crimes he was hanged and skinned. Why did they skin him? Well obviously to make wallets, lampshades, and book covers. These corpulent keepsakes are said to still exist and one of them is housed at the NJHGC where Weird New Jersey came and did a story about it. The Genealogy Center also has Leblanc’s death mask, which arguably is not as intriguing as the wallet, yet still quite eerie. Every year a retired judge does a presentation on the story.

Since we are talking about archives, it would be unfair to leave Jacques Derrida out of the equation. In Archival Fever: A Freudian Impression, he says that the archive, “keeps, it puts in reserve, it saves, but in an unnatural fashion, that is to say in making the law […] or in making people respect the law.” Archives and the power they hold have long been a scholarly issue and the reason one brings it up here is because the Antoine Leblanc wallet and death mask easily tie into this debate. These artifacts are a haunting reminder of an atrocious crime, as well as the atrocious way the criminal was dealt with. Thus, we are not allowed to forget the barbarity of man towards man and in turn, are subjected to an adverse view of mankind. This is a grim way of viewing archives individually or Derrida’s overall Archive as a whole and only works under certain conditions, as in when governments do not allow the people access to them. What we should take away from the Leblanc artifacts is something much less sinister; archives do not have instructions as far as what can and cannot be put into them.

Leblanc’s death mask reminds one of the skull of Hamlet’s poor Yorick. Coincidentally, the Genealogy Center is home to the Morristown Shakespeare Club minutes, which date back to 1878. The club is the second oldest in the United States and was founded by all women, which was very rare for the time. After each one of their meetings, the minutes are delivered to the archive, which deposits them in boxes and is currently in the process of digitizing them. In spite of this, the North Jersey History and Genealogy Center is a place where the printed page still takes precedence over the computer screen, which is quite refreshing.

Works Cited

Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. Print

Schwartz, Joan M., Terry Cook. “Archives, Records, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory.” Archival Science 2 (2002) 1-19. Print.