Adding Accessibility to the Digital Strategic Plan?

April 13, 2019 - All

Throughout the course Museum Digital Strategy, we have discussed whether museums need a digital strategic plan across their whole institution, or if the museum can entrust that responsibility to individual departments who can craft their own digital plans as they see fit. Accessibility within the museum space can be looked at in a similar fashion, because like digital it is intertwined within many facets of the institution, and the organization can seek to continually add accessible components. Digital and accessibility projects frequently overlap, so there is the potential for museums to craft a joint strategic plan to move both aspects of the institution forward and in tandem.

Similar to the rapid development that has occurred in the past 20–30 years within the field of technology, accessibility issues have increasingly come to the forefront of cultural institutions after the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) occurred in 1990. Since then, both digital and accessibility lenses have been added to almost every department and project within the museum sphere from their website to their physical space (Osterman 2018; 12). Additionally, it is important for the digital website to highlight how accessible the physical space is, and for the website to reflect the accessibility of the institution (Cock; 1). It seems only natural to suggest that they might work and develop more effectively together in a unified digital and accessibility strategic plan, especially because they both impact the trajectory of the museum, are involved with every department, and have been interacting and growing at similar rates for the same stretch of time.

In an ideal world, accessibility and digital are engrained in every department and project that the museum undertakes. The mission of strategic planning is to goal set, timeline, and show the desire to the donors to stay relevant. As institutions look towards the future and try to cater their content to the widest audience possible, they can create a strategy that helps move both their museums accessibility and digital undertakings forward. Statistically, around 19% of people are considered to have some form of disability (Osterman 2018; 12). There is not one universal approach to creating a better experience for visitors with different abilities, but creating content designed for different people often helps a large number of varied learners and levels of ability, not just the patrons who need the added features of the space. As kids grow up knowing how to adapt to digital technology, and the large generation of baby boomers age, there will continually be an increased need for museums to add more features addressing accessibility and technology (Osterman 2018; 12).

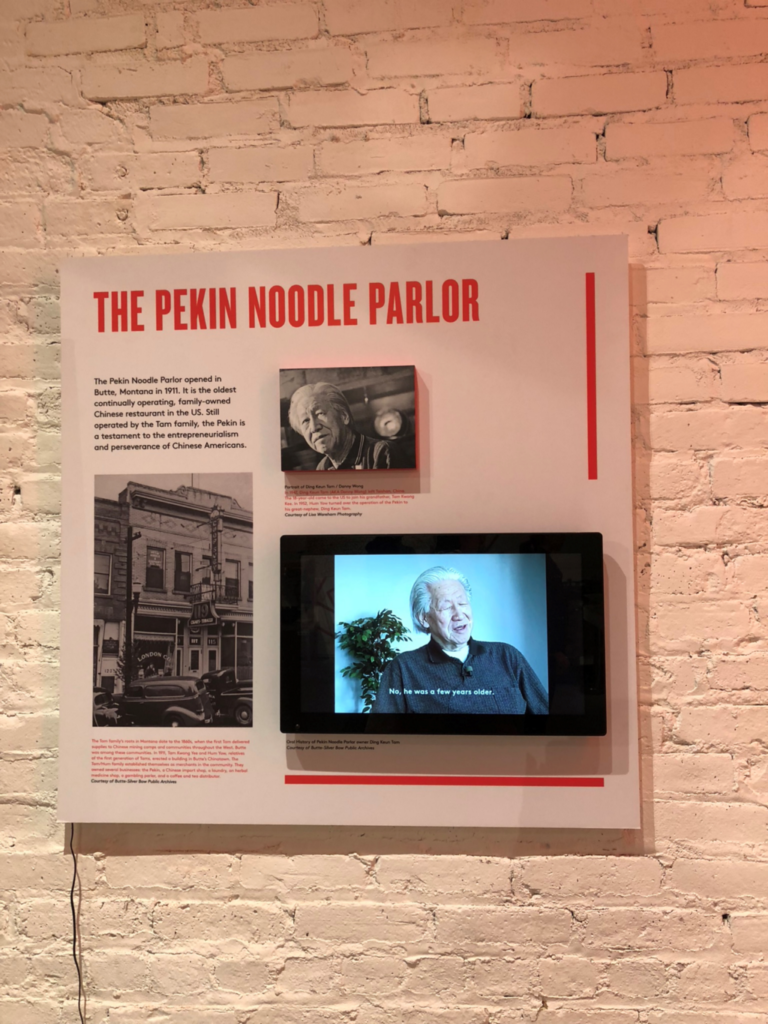

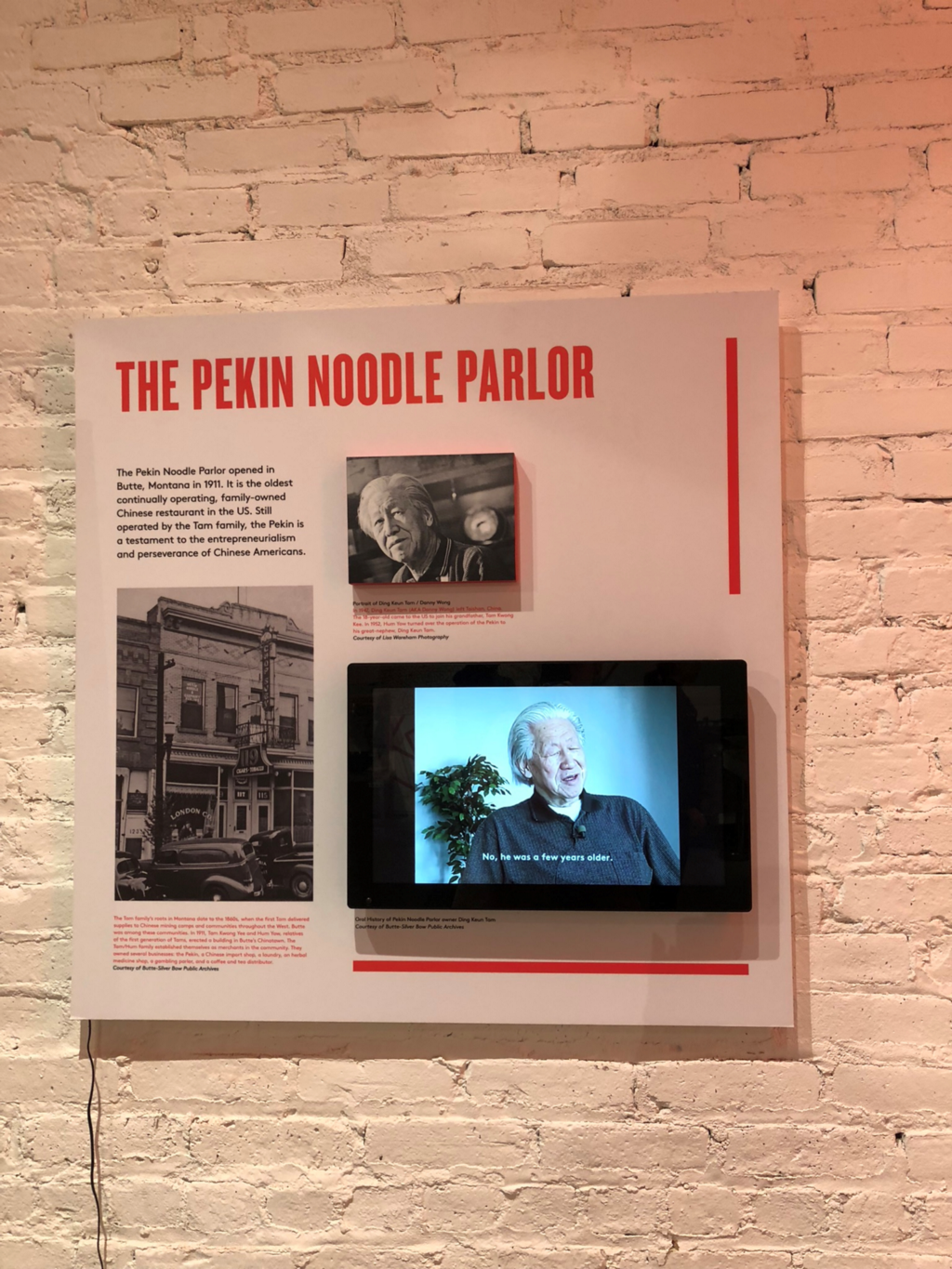

There are numerous examples of accessibility and digital working successfully together in museums. Recently, I went to the Museum of Food and Drink (MOFAD), and it is evident they are from the creation of the museum, attempting to infuse digital and accessible components, though it is still an apparent work in process as they are still working on getting funding. They are creating a very sensory experience for all five senses and including digital elements that are accessible in multiple ways.

On a larger more permanent scale, the Whitney Museum of American Art has taken a strong approach to increase accessibility and digital components cohesively, and it is apparent how much focus they have put into the details of their exhibits, and digital components to create an impactful exhibition experience. From their website to their exhibit, every part of the Whitney experience seems to be thought of with the consideration of a wide variety of viewers.

While there are numerous benefits that could be created by writing an accessibility and technology strategic plan document, there are a few initial potential problems with this combined field. For starters, while the overlap quite frequently, there are occasional instances where digital projects and accessibility projects would not intersect. While those projects could likely both end up in the same document, there could be the potential for projects that don’t further both accessibility and technology, to be given less priority then the projects and goals that are focused on furthering the development of both. For example, on the accessibility side, things like ramps and detectable warnings have little to do with increasing digital in the institution, but including those features helps visitors in wheelchairs as well as parents with strollers. Likewise, projects like creating a mailing list database, while important to the running of the institution, does not necessarily directly impact the visitor of the institution at whatever level of ability they are. However, there is seemingly enough overlap, and often the digital and accessible projects are one in the same. Creating applications, audio tours, 3-D printed sculptures, larger artifact descriptions, well-lit exhibit spaces, captioned videos, and many more projects benefit not only a large number of visitors but also helps to advance both technology and accessibility within the space (Anable, 13). Another large problem, as is frequent in museums, is the monetary expense behind the goals. While accessibility and digital projects are investments in the future of an organization, having the head of an institution create big lofty and expensive goals for each department to adhere, might cause some problems if there is disagreements within departments of the museum. The added debatable predicament behind this, involves the fact that there are minimums a museum can do to legally adhere to have their institution be considered accessible. Digital technology and accessibility within digital is not as regulated or easy to control. Convincing institutions to take steps to be increasingly accessible beyond the bare minimum legal requirements might be a challenge especially if funding is limited, leading for a strategic plan to be incredibly reasonable, achievable and well thought out.

Additionally, both fields are always changing. Digital and accessibility are very new factors in the museum field, and there had yet to be a universal approach that works well enough that it becomes a universal design across a wide variety of museums. Potentially the longer the fields exist, a more universal approach could emerge. However, creating a long-term plan for accessibility and digital can be challenging, because innovations are constantly occurring, different needs are being met, and the internet looks a lot different then it did ten years ago. Trying to project and plan for the future in both of these fields is not an easy, cheap or quick task, but combining them might be the next step in museum management. Creating a joint force to bring the museum into the future, and make sure there is a focus on accessibility and digital within the institutions mission can allow for a stronger focus as they continue to make content for the future.

Sources:

Anable, Susan, and Adam Alonzo. Accessibility Techniques for Museum Web Sites. 2001, p. 1–14.

Cock, Matthew. “Help Improve the State of Museum Access 2018.” VocalEyes, 2018, p. 1.

Linzer, Danielle. “Learning by Doing: Experiments in Accessible Technology at the Whitney Museum of American Art.” Curator, vol. 56, no. 3, July 2013, pp. 363–67.

Lisney, Eleanor, et al. “Museums and Technology: Being Inclusive Helps Accessibility for All.” Curator: The Museum Journal, no. 3, 2013, p. 353–361

Museum of Food and Drink https://www.mofad.org/

Osterman, Dr. Mark D. “Accessibility and Technology: Developing A Virtual Access Tour” MW17: MW 2017. January 2017, p. 1.

Osterman, Dr. Mark D. “Museums of the Future: Embracing digital strategies, technology and accessibility.” Museological Review, issue. 22, 2018, p. 10–17.

Whitney Museum https://whitney.org/

Adding Accessibility to the Digital Strategic Plan? was originally published in Museums and Digital Culture – Pratt Institute on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.