Ways of Seeing Virtually

April 4, 2020 - All

An essay on the digital trend virtual reality in museums and in the wider cultural sector. Completed for Info 683: Museums and Digital Strategy.

At the Night of Philosophy and Ideas, an all night event hosted by the Brooklyn Public Library, a room was dedicated to two virtual reality projects. One was an animated post apocalyptic story about a zombie and a human in love titled “Gloomy Eyes,” the other was an immersive experience into the painting “The Dream” by Henri Rousseau titled “Dreams of Rousseau.” The storyline of the latter put the user in the role of a visitor in the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, the greenhouse that served as inspiration for the painting. As the garden closes, the user-as-visitor remains behind and experiences a dream like immersion into the garden inhabited by the flora and fauna represented in the painting. The experience is beautiful, slightly disorienting, and very engaging. You are inside of the painting, listening to a ghostly voice narrate the dreamy, magical experience inspired by the same garden that inspired “The Dream.” Returning to reality, one feels as though they’ve seen the painting from the inside out. They have experienced an idea previously only visualized in a painting, as a new and entirely virtual reality.

As virtual reality becomes more mainstream in entertainment industries as well as the cultural sector, it is worth exploring the implications of using virtual reality to experience art and history inside the museum space and outside of it. Does “Dreams of Rousseau” add something special to understanding this painting? Is this kind of virtual reality, and other similar projects, simply a novel experience or an enhancement for understanding art history? How does the methodology of creating these virtual experiences affect how visitors understand history, reality, and academic research? What are the implications of using virtual reality to experience art?

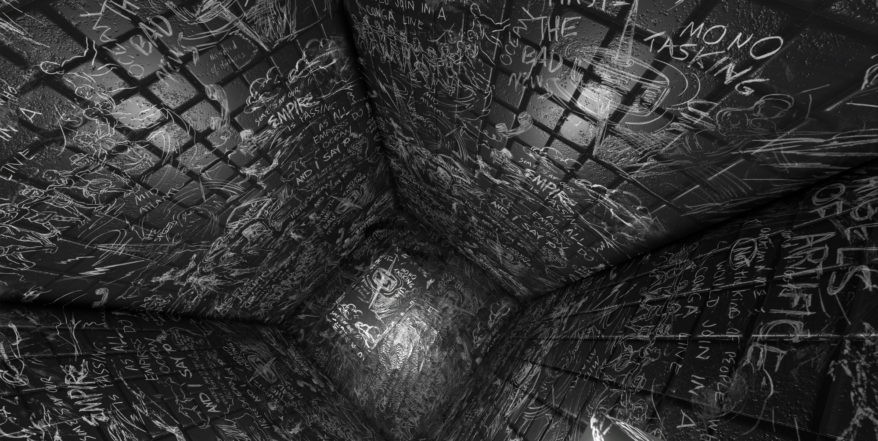

In the museum sector, there are three main applications of virtual reality technology: artists who use virtual reality experiences in their work (Anderson, 2017), museum exhibitions that incorporate virtual reality to teach, display, or engage visitors (Tate; Musée du Louvre), and virtual reality for accessibility tours and experiences (Hetherington and Pavement, 2018). Each application requires different resources, intention, and expertise. Exhibitions such as Laurie Anderson’s “Chalk Room,” located at MASS MoCA in North Adams Massachusetts, is an example of an artist using virtual reality as an artistic medium. Museums such as the Louvre in Paris to the Tate in London have used virtual reality as a tool for designing exhibitions, allowing visitors to engage with works of art, virtual spaces, and history in new ways. Many museums are also experimenting with virtual reality to allow visitors to visit the museum remotely, allowing for visitors of various physical abilities and economic resources to enjoy collections.

The focus of this brief essay will be on virtual reality experiences designed by museums as part of a larger exhibition. The intention is to explore the effect these experiences have on visitors, the authority they represent for the museum in creating a historical reality, and to situate the trend of virtual reality museums within broader trends in technology in contemporary culture. In attempting to understand the ways that experiencing virtual reality affects our understanding of art, history, and reality, I am indebted to John Berger’s analysis of viewing art in an age of reproduction, television, and media.

Two exhibitions that centered on virtual reality experiences offer art historians, museum professionals, and software developers interesting case studies for considering how to fabricate what is not physically, temporally, or logistically accessible. At the Tate in London, the “Modigliani VR: The Ochre Atelier’’ goes behind the scenes in a virtually fabricated experience of the artist’s last Parisian studio. At the Louvre in Paris, the “Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass” was an integral part of their Leonardo Da Vinci exhibition for experiencing one of the most famous paintings in the world.

Each of these virtual reality experiences served a different purpose. For the Modigliani exhibition, virtual reality immersed the visitor in a space that was previously “unvisualized,” meaning that depicting this particular space relied on “Using the actual space as a template, as well as first-hand accounts, historical and technical research” (Tate). Like most places from the past that have changed over time, we rely on images, artifacts, written accounts, oral histories, and if available, access to the physical space as it remains to further document a memory of that space and to evoke descriptive understandings of a space. Generally, the visual aspect is left to the imagination, pictures, or possibly film set replications. With all of these standard tools of visualization, the act of seeing is affirmed by the bounds of the media — the edges of a piece of paper, the frame of screen. To actualize that space using virtual reality takes this process a step further, and in doing so adds an entirely new element of authority over previously unseen spaces. The immersion into a virtual space removes the typical constraints, or bounds, of experiencing media and of engaging with visual reproductions.

c/o Preloaded via tate.org.uk

The “Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass,” spoke to the unique needs of the iconic museum that is home to the most visited work of art in the world. In preparing for their Leonardo Da Vinci exhibition which recently ended, the museum had to contend with the sheer volume of visitors that this one painting receives every day. The Mona Lisa is notoriously popular for its style, the artist, and simply for it’s recognizability, namely, for being famous. It has become a spectacle in that the experience of viewing this work cannot be uncoupled from the experience of watching others look at this work. The virtual reality experience created in partnership between the Louvre, HTC VIVE Arts and produced by VR studio Emissive, sought to engage visitors in novel ways given the currently impossible or rare ways of typically seeing a work of art. The VIVE Arts website describes the project, “Alone with the masterpiece in the virtual space, the visitor can see the vivid details of this celebrated oil painting, including the texture of the wood panel seen through the paint layer, and the marks where the panel once cracked and was masterfully restored” (VIVE Arts). This virtual reality experience at the Louvre allows visitors to engage with this work of art in personal, detailed, engaged, and informative ways that are otherwise impossible given the cultural significance of this work and the number of visitors in the space.

In these two cases, a work of art and a historical space are fabricated by VR studios informed by deep and diligent research. The effect is that visitors are able to engage with works of art and historical spaces in ways that are temporally or logistically impossible to do without technology. As more facets of life become mediated by screens and technology, it is crucial to understand what benefit virtual reality experiences offer in art museums, and when virtual reality experiences are simply novel forms of entertainment.

Museums are considered highly trustworthy conveyors of information. There are interesting epistemological concerns with designing immersive spaces that visually speak for spaces previously unseen. When spaces and works of art are recreated virtually, there is considerable authority taken in creating and displaying that reality. Do these virtual spaces become perceived fact once they are employed in a museum setting? In “Dreams of Rousseau,” considerable liberty is taken in what information is portrayed, because the use of virtual reality is intentionally to create a novel experience. However one still leaves that experience having gained a new understanding of the painting. Cultural organizations and design firms conveying visualizations as realities, particularly when employed in museums, have a unique obligation to convey information accurately, while also describing the methodology of how decisions were made, what their sources are, and the limitations of the medium of virtual reality.

Sources

Anderson, Laurie. “Chalkroom.” 2017. Laurie Anderson. http://www.laurieanderson.com/?portfolio=chalkroom (March 2020).

Arte. “The Dreams of Henri Rousseau.” Arte. https://www.arte.tv/sites/en/webproductions/the-dreams-of-henri-rousseau/ (March 2020)

Berger, John. “Ways of Seeing.” Great Britain: Penguin Books, 1972.

Hetherington, Amy and Peter Pavement. “‘Virtual Accessibility’: Interpreting a Virtual Reality Art History Experience for Blind and Partially Sighted Users.” In Humanizing the Digital, edited by Sue Anderson, Isabella Bruno, Hannah Hethmon, Seema Rao, Ed Rodley, Rachel Ropeik. 96–100. Ad Hoc Museum Collective, 2018.

Lee, Hyunae, Timothy Hyungsoo Jung, M.Claudia Tom Dieck, and Namho Chung. “Experiencing Immersive Virtual Reality in Museums.” Information & Management, 2019, 103229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2019.103229.

Morales-Marin Javier, Juan Luis Higuera-Trujillo, AlbertoGreco, Jaime Guixeres, Carmen Llinares, Claudio Gentili, Enzo Pasquale Scilingo, Mariano Alcaniz, Gaetano Valenza. “Real vs. immersive-virtual emotional experience: Analysis of psycho-physiologicalpatterns in a free exploration of an art museum.” PLOS ONE, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223881

Musée du Louvre. “Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass.” VIVE Arts. https://arts.vive.com/us/articles/projects/art-photography/mona_lisa_beyond_the_glass/ (March 2020).

Rea, Naomi. “The ‘Mona Lisa’ Experience: How the Louvre’s First-Ever VR Project, a 7-Minute Immersive da Vinci Odyssey, Works.” Artnet. https://news.artnet.com/exhibitions/louvre-embraced-virtual-reality-leonardo-blockbuster-1686169 (March 2020).

Tate. “Modigliani VR: The Ochre Atelier.” Tate. https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/modigliani/modigliani-vr-ochre-atelier (March 2020).

Ways of Seeing Virtually was originally published in Museums and Digital Culture – Pratt Institute on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.