“Build the data and they will come” Thinking Digitally in MoMA’s Archives

February 13, 2020 - All

Last week I had the pleasure of speaking with Jonathan Lill, an archivist at MoMA who is working at the forefront of Linked Data projects in the museum world. We spoke about his journey into the world of archives, particularly the digital practices and strategies that enhance and enrich data in a seemingly object-oriented field. As a student interested in Linked Data, I have always been curious about the user and how Linked Data addresses or has the potential to address the needs of researchers. Jonathan has worked on several projects at MoMA, but two of his largest bodies of work include the MoMA PS1 archive and the MoMA Exhibition history. During our interview Jonathan made a statement that poignantly summarizes the potential of the digital projects happening in the archives, “Build the data and they will come”. Keep reading to learn more about his work, and how digital intervention is helping MoMA’s archives get stuff done.

Okay so my first question for you is, what is your official title?

“My official title is the Leon Levy Foundation Project Archivist. The Leon Levy Foundation is wonderful, they’re a personal foundation run by Shelby White, Leon Levy’s widow. The Levy name is on the Greek and Roman galleries at the Met, but for the last decade or so, have really turned to support archives of cultural organizations in NYC, so they’re very local. It really has been a wonderful local resource, that we’ve been very fortunate to receive some of their largess.”

What brought you to MoMA?

“Well luck, I mean certainly the right job coming at the right time. I have a BFA, I studied studio art as an undergrad, that was in Illinois. But when I decided it would be good to go to library school, I was in Boston. A number of things drove me to library school, an interest in rare books, a strong interest in history. Simmons College in Boston where I went has a strong archives program so I realized that studying archives was a great way to interact with historical materials. At the same time, I was conscious of my art background so I took a class in art librarianship, I also ended up really liking cataloging so I took a couple extra cataloging classes. I was really looking at art library special collections, rare book special collections at universities for jobs, that’s kind of where I thought would be happy. My first job was at Columbia, Rare Book Manuscript Library, that was a Mellon Grant, then I was a Kress Fellow at Yale Art Library, and I worked a little bit at NYU. Then I was unemployed for a stretch of two or three months but this job opened up at MoMA it was a grant job. Like so many archives jobs it was temp funded, it was to process organize, and describe a couple of small collections. I did that, and I certainly didn’t know that I’d be here 12 years later.”

When you speak about your archives journey, it feels very physical, like working with rare books and working with. Can you talk about what led you to the digital?

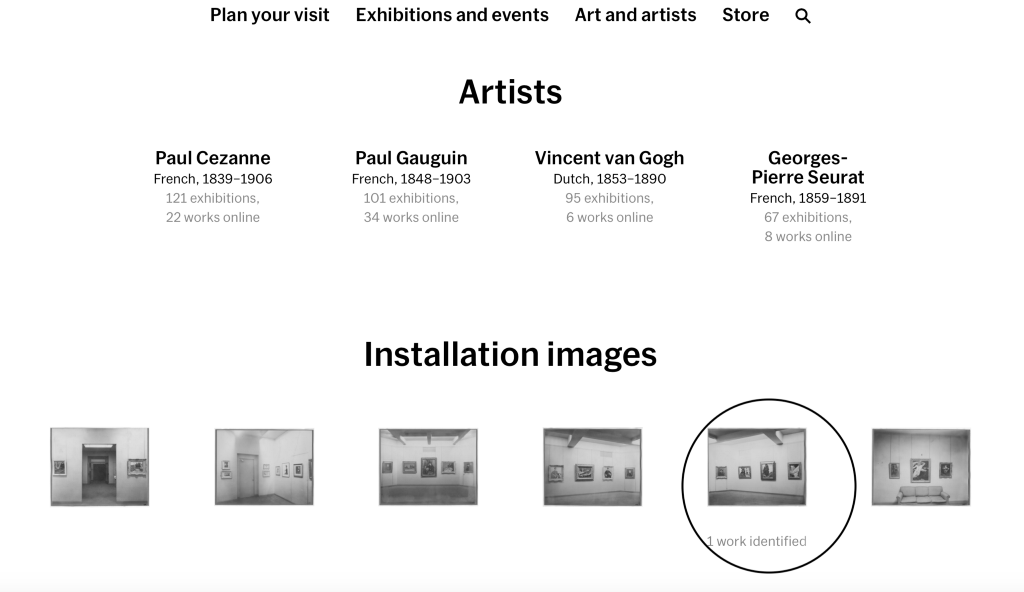

“Prior to library school, I got a job as an Office Administrator in a graphic design firm. In order to get the job, I essentially had to promise to build a database for them, and I really started loving databases. And then I went to library school, and I didn’t realize databases had so much to do with libraries or the information side of library science. And the fact that I loved cataloging took me by surprise, and that’s all systems management. I had the interest built in, and having technical proficiency ends up coming in handy more than I thought. And when I was hired at MoMA, one of the reasons I was hired was because I have XML, and EAD experience, familiarity with HTML and I had this database stuff that all contributed to my qualification for this position. That said only when I started the PS1 Archives did I use a database as the center of my workflow, and that’s continued so that fellow archivists Katie Rovanpera and Tellina Liu are using an Access Database as the center of their processing. It proved to be a useful tool. I was told apart of this project was to establish a reliable complete exhibition history list of MoMA PS1, because none had ever been made public, so that was always hard information to find. And I realized if I was doing that in this database system then it would be possible and probably useful to just mention what artists where in each show but to do it in a database structure so you could produce reports, so you could sort and filter and things like that. So when the MoMA Exhibition Files project files started up, Michelle Elligott (MoMA Chief of Archives, Library, and Research Collections) asked me to do the same thing for MoMA, build artists names into the exhibition data structure. At that time, I had been working at MoMA long enough, and I’d become more familiar with MoMA’s systems I had a better idea of what would be useful and feasible. So what I did, that I hadn’t done for PS1 was export the name and exhibition records out of TMS(MoMA’s collection management system) and matched those artists names so all the artists’ names in my personal database have TMS identifiers in case the records ever needed to interact with one another.”

How has this work led you to think about Linked Data?

“I’m using a database to produce a finding aid, in this finding aid I could link out press releases and other materials in the finding aid. A lot of the indexing putting the artists’ names into the database attached to specific exhibitions, getting that information out of a discreet document called master checklist. It might be easier to do that work, and also convenient to scan those cheaply and put them online which will really help the indexing going on. Once we had those, I put the names of the files into the database so that wherever they ended up online, I could just build URLs off the file name.”

In what ways are you thinking about the user, when structuring data?

“At ARLIS (Art Libraries Society of North America) this year, I heard a couple of jokes, about how it’s really still always about spreadsheets because the technical levels of most scholars and librarians aren’t high enough to really make it easy to spread Linked Data in Linked Data Format, or for people to interact with it at that level of coding. That’s why you see that type of information published on Github, collection data published as a spreadsheet. I think that’s important and very very useful, even when you go on to later then do complicated things. It’s interesting taking digital marketing classes because its very important for the website and things like that. The user they keep in mind is a very casual user, the person who may not know anything about art, maybe a tourist who wants to go to MoMA. That’s a major way they view the website, that’s their user base. So for instance, our history pages, as useful as they are to scholars, they don’t have a complex search interface or filtering function. They’re not operating at a level of data, they’re operating at a level of page content. And that’s appropriate for the audience that’s our main concern online. If I was at a university, I may design the search interface in a different way so there is more flexible filtering in the search interface . These are things I would like to see happen, but as an organization, you see the priorities and being able to fit in with those priorities in any way is a victory for a smaller department like Library and Archives. As someone who thinks of himself as a data person, there’s a lot of things you can do with the data, that’s not possible yet on the website. Like is there a way to publish it as Linked Open Data that will make it more useful for a certain narrow audience. We haven’t quite identified that audience yet, who are those people?”

Is there a future when museums will create some type of interface to convey the information and relationships Linked Data produces?

“That’s entirely the thing. Publishing Linked Data as raw Linked Data, like American Art Collaborative and SAAM, they have their collections expressed as Linked Data on their website. It’s interesting to think about that in terms of who is using it, what audience. I’d like to know the size of that audience what the feedback of that is. I think the more broad use of that application is however we store that data, but the main use is to build an interface that draws very richly on the relationships in the data. Certainly, we’ve taken care to structure our data so that we can characterize connections between individuals and exhibitions. Those characterizations are very rich on you should be able to limit by them, filter by them.”

When considering those relationships are you anticipating the needs of your audience?

“Yes, totally. A lot of this has been me poking around in the dark saying. ‘This feels like it would be supremely useful to researchers’ actually not knowing if it would be or not. Just having a gut instinct saying this is cool being able to map the exhibitions by reconciling institutional names to addresses, for instance. Making sure those addresses are historically accurate, taking care of subtilties in those kinds of basic data bits. So it’s not a big jump to say it might be important to know where these things happen. If we reconcile it to a street address or a Geolocation than we can put it into a map system. It seems like a really good way to put this data to use, to use a map interface, or a graphically interface seems like a good way to browse. Likewise, a timeline interface to browse chronologically. The same thing with reconciling the names to outside authorities, as a librarian cataloguer, I really appreciate the power of authority records and linked authority records.”

To end our interview, I asked Jonathan for his Rose, Bud, and Thorn in regards to digital projects in the archives. Rose denotes something he’s happy with, Bud is something he’s excited about, and Thorn is a dissatisfaction or something he wish would change.

Rose ?

“Certainly very satisfied with the work we’ve done so far on our integrated exhibition index.”

Bud ?

“This project is still in the experimental stage and I am very curious to know and to find out what the next stage of growth will be because a lot of people are excited by it. But it’s still unclear what that means in practical terms, in the short term.”

Thorn ?

Well you know, when you get enthusiastic about something it’s frustrating you can’t just do the thing you’re excited about doing at the moment. Things take time to change, and get done, things happen not in terms of months but in terms of years. Like if I dream about it tonight, why can’t I make it happen tomorrow. You want these slow currents of interest and enthusiasm to happen tomorrow because it would be so useful to you.

Some takeaways….

- 3000–4000 pages of MoMA Exhibition History online

- MoMA wanted exhibition history to be exactly in sequence with their new exhibitions. (As opposed to “What’s On Now”, “What’s Coming”)

- moma.org organizes its exhibition history through a calendar system to run their exhibitions, events, and activities portion of the website. Which makes it very easy for them to stop, start, say what time of day as well as record different types of events (performance, film screenings, etc…). The calendar system uses a unique calendar ID, as opposed to a TMS ID.

- Good data and well-structured data is very important!

My conversation with Jonathan left me with more questions than answers, which as we all know, in the world of information is a good thing. I am curious to learn more about the intended audience for Linked Data resources. As Jonathan mentioned, those users look differently from folks visiting a museum website looking for information on parking or ticketing. Nevertheless, they are still a stakeholder in the digital plan of departments like MoMA’s museum archives.

Further Reading:

http://americanartcollaborative.org

“Build the data and they will come” Thinking Digitally in MoMA’s Archives was originally published in Museums and Digital Culture – Pratt Institute on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.