Interview with Douglas Hegley

April 29, 2019 - All

Chief Digital Officer at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia)

By Gloriana Amador Agüero

Back in1915, in the Twin Cities of Minnesota, the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia) opened its doors to inspire the community through art and creativity. With more than 89,000 objects, visitors have enjoyed art from diverse cultures displayed in this magnificent neoclassical landmark.

Mia is recognized for its level of innovation, interactive media programs, and digital initiatives. Today, we are having a conversation with Douglas Hegley, Mia’s Chief Digital Officer, who is going to share with us about his work in the digital life of Mia, his perspectives and thoughts regarding audience engagement, and his fascinating journey into the museums’ world.

First of all, can you tell us about your position as Chief Digital Officer at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia)? Your areas of focus and current projects?

As Chief Digital Officer at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, I sit on the museum’s executive leadership team, reporting directly to the CEO — a strong indication of the museum’s commitment to digital technology as a strategic business partner. My position may be slightly unusual, as it combines the responsibilities of CIO and Executive Producer, ranging from technology infrastructure to content production. I oversee the Media and Technology division, which consists of six departments, each led by a dedicated manager:

- Information Systems (IT, user support, security, telecom)

- Software Development (website, APIs, transactional systems)

- Collections Information Management (archival database, standards, licensing)

- Digital Strategy (project management, administration)

- Interactive Media (video production, audio production, in-gallery display installation)

- Visual Resources (digital photography, 3D imaging, photogrammetry, digital asset management)

The division includes 21 full-time staff and 7 part-time employees, along with 2–4 interns depending on time of year. The operating budget for the division represents about 8.5% of the $35 million organizational total — another indicator of the commitment to a strong technology operation. Similar to most digital technology units, we are constantly juggling multiple tasks and projects, guided by the museum’s mission and strategy. In terms of priority, the current top three strategic objectives are (1) delivering a cutting edge CRM solution built on Salesforce to drive segmented marketing and increase customer loyalty, (2) providing engaging digital content via video production and cutting-edge 3D and photogrammetry, and (3) driving hard on continuous innovation, modeling Agile working methods and the application of new technologies to a century-old business. As they say: never a dull day!

You are a strong advocate to empowering and transforming staff and organizational cultures with technology and innovation. Can you mention one of your most successful cases? And, what did you learn from it?

My leadership style can be labeled as Host leadership. It is deeply informed by my educational background in psychology, and involves leading from within rather than through hierarchical authority. A Host leader nurtures an inclusive and trusting workplace, brings together the right people, and participates actively with the team to get things done. Our workplace culture is dynamic, with decision-making spread across the staff. Host leadership empowers self-organized teams to use the methods and tools they choose, which results in faster completion rates and higher worker satisfaction and retention. We work via strong and disciplined collaboration, without concern for hierarchy. We don’t rely on organizational structure — success comes from self-organized, self-directed teams of talented individuals who work together with agility and generosity to deliver on a large portfolio of projects and activities. For example, to delight our customers with new digital content, we formed a team that dubbed themselves The Digital Experience, or TDX. The TDX team is made up of 5 individuals from 4 different divisions, working together to design, create and share stories and insights with our visitors. As Executive Sponsor to the team, I primarily review strategy and help remove obstacles they may encounter. I don’t define their working methods, storytelling approach, or deliverables — they do so themselves. To date they have delivered a website rebuild, published 100 new digital stories, built three new software platforms, created 30 documentary films, and completed over 40 installations of digital interactive devices in the museum’s public space. Customer feedback has been overwhelmingly positive.

For more on Host Leadership, this blog post frames the concepts nicely.

After having worked in the field of pediatrics in research, you joined The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1997. That’s a significant change in someone’s career. Can you share with us what led you to work for the museums’ field?

Perhaps ironically, I never imagined that I’d work in a museum setting. I have always loved museums, and particularly art museums. My father was a high school art teacher for over 35 years. When I was a child, we took vacations just to see art museums and natural history museums! But I had different career goals. I studied clinical psychology at the PhD level, and planned to be a therapist. But changes in that sector, primarily the rising prevalence of treatments based on drugs instead of therapy, caused me to re-assess those plans. I spent a couple of years working in pediatrics, primarily in research around parent-child attachment, particularly in families with infants born with severe disabilities. I was also teaching part-time, but frankly I wasn’t quite sure what to do next. As luck would have it, I met some folks who worked at The Metropolitan Museum of Art — one of my favorite places to visit — and they were talking about the difficulties of rolling out desktop computing. It was the late 1990s, and they knew that the museum was behind the curve, but there was resistance from a large portion of the staff — who felt that technology was essentially being forced upon them. I had an interest in the areas of conflict resolution and organizational development, and it sounded like I might be able to be of help if I put myself into that mix. It didn’t hurt that I was a *fan* of desktop technology. I had no formal training in computing, but I was an early adopter of home computers and knew I could teach others how to make the best use of desktops. So I put my hat in the ring, and I was lucky enough to get hired. I didn’t think I’d stay more than 2 or 3 years, but once I was fully-engaged with helping The Met with what we now call ‘digital transformation’, I kept finding more and more fascinating work to do. I ended up working there for 14 years.

Initially, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, you helped to create collaborative ways to work with technology, and later on with the digital content. What were your major challenges at that time in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and how did you solve them?

There were plenty of challenges at The Met, and there are two things I’d like to emphasize right up front: (1) Most of the challenges were natural, that is, in an organization with as deep a history and many decades of ensconced workplace culture, there are going to be major challenges with anything that creates change — so The Met wasn’t some kind of special case nor was it in any kind of major crisis, it just needed help with moving along into the 21st century; (2) When you ask how I solved the challenges, my first reaction was to say that I alone didn’t solve anything! My approach to any issue is to build a collaborative team based on mutual respect and shared goals, and then to work as part of that team to get things done. I can’t think of any important thing in my professional career that I actually accomplished all by myself. It’s just not how I work.

One of the ways that we approached the task of asking so many employees at The Met to embrace new ways of working (using computers) was to make sure that we did that in a transparent and collegial manner, which was always aligned with the mission and vision of the museum. With the Director’s approval, we formed a large “computer liaison group” with representatives from each and every department. We held frequent, large-group meetings at which I always spoke about why we were moving forward, presented clear next steps, and then facilitated discussions about everyone’s concerns, issues, etc. We practiced empathy and active listening to demonstrate a deep understanding of what people were experiencing. But it’s not enough just to hear about people’s struggles, what matters more is (a) making a plan to help, and (b) actually *doing* something helpful. I think our key early wins were based on that formula: Please tell us what’s not going well, here’s how we are going to help, and then *delivering* on that plan. I realize that may make it sound pretty simple, and I promise you that there were plenty of bumps along the way, but that foundation of active listening, trust and follow-through helped everyone move forward.

In 2011, you joined the Executive Team of the Minneapolis Institute of Art. New York and Minneapolis can bring different experiences in someone’s career. From a digital perspective, can you tell us about the differences and similarities in both institutions? As a museum professional, what are the main lessons you have taken from both scenarios?

Well, first of all I’m an unabashed fan of both museums — and I visited both long before I ever imagined working at either. From my current perspective, they are both major encyclopedic art museums with wonderful collections featuring several true masterpieces; both are important cultural anchors in their respective communities, helping to cement the reputations of their respective cities as cultural destinations; both museums employ top-notch staff, are dedicated to scholarship, and have been successful for over 100 years. Pretty impressive.

Of course, there are also major differences. The Met is much larger in size, collection, foot print and visitor numbers. It is also much older, and enjoys a well-deserved international reputation. Partly due to its location in New York City, The Met sees a huge amount of tourist traffic. For many staff, working at The Met represents the pinnacle of their careers. As far as organizational structure and workplace culture, it is relatively siloed and authority-based — permission is a necessity before embarking on anything new or different.

Mia may be smaller, but that means that it is more nimble and far less risk-averse. Mia enjoys a very dedicated local customer base and sees very little tourist traffic (that changes a lot of things, from marketing to a focus on experiences to finances to the importance of repeat visitation). As far as organizational structure and workplace culture, Mia is “flatter” without such clearly delineated siloes, and it is a more collaborative workplace where effective cross-functional teams are given the leeway and resources to make decisions for themselves in order to get things done.

Working at both places has provided numerous lessons and insights for me professionally and personally. Thinking of The Met, it was truly the place that provided me with the opportunity to reset my career path and find a real calling. No doubt I grew tremendously from my experiences there. I learned so much about how museums function and especially about the curatorial mindset. I look back now and of course I see that I made my fair share of mistakes and errors, but I think I was able to learn a lot from them. Perhaps the bottom line is that I essentially grew up professionally at The Met. Moving to Mia provided me with an opportunity to take a significant step up in terms of role and responsibility. With that was the chance to focus on implementing more dramatic and rapid changes, including overall strategic planning and direct influence on workplace culture. I have been able to build a new team, to drive on innovation, and to be involved in a wider range of museum activities across all functions. Maybe most of all, it’s been wonderful to experience an empowered workplace, where authority is respected but is not the one-and-only voice in making decisions.

For me, both places are great in their own way and in many shared ways too, both are seen as leading lights in the American museum sector, and both places have truly felt like ‘home’ while I spent my days working to contribute to the success of each.

During the conversation with David Lipsey at Henry Stewart Digital Asset Management New York in 2015, you mentioned that a museum is not a museum until it opens the doors and engages with the public. Can you tell us about the best digital practices related to this idea that you have known during your career? And, which one has been of inspiration or reference to you?

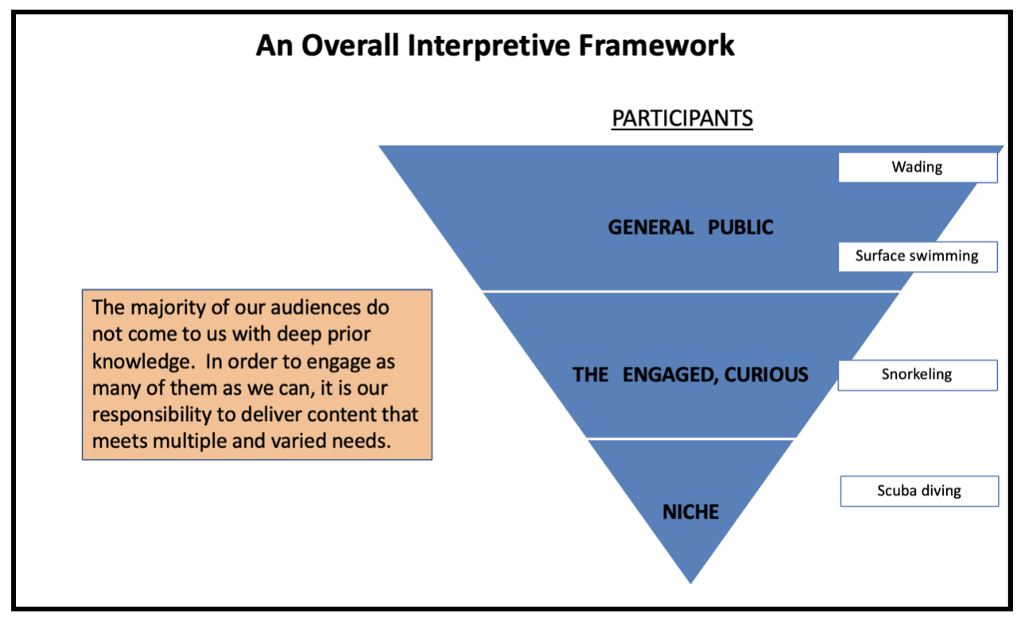

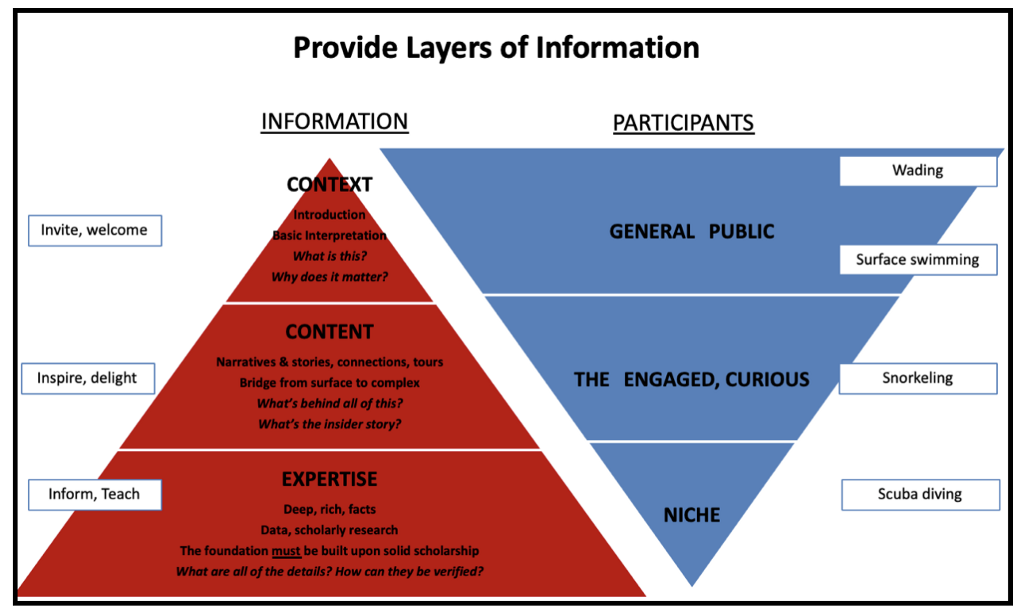

I believe you are referencing the video I recorded with David Lipsey. The metaphor I’ve used is that museums would be nothing but warehouses if we did not share our magnificent collections with the public. That mandate to share is a vital purpose that all museums work hard to fulfill. There are of course many ways to share our collections, ranging from displays to study rooms to special exhibitions to loans to printed books and — near and dear to me — digital channels. Digital has some very real strengths that it can take advantage of in this regard. First and foremost, with good digital content production comes the ability to provide layers of content. It’s probably easiest to illustrate this, with an analogy thrown in for good measure.

This is not, and never will be, “dumbing things down”. Instead, this is opening as many doors as possible, and meeting our audiences where they are, with respect and enthusiasm. Let’s use the analogy of a beach resort. Most folks come to relax, and may only dip their toes in the water or do a little swimming. Only a tiny fraction go scuba diving. But the staff and the resort happily welcome all of them, and provide the experiences they seek, without judging them. Museums can do the same by providing our many audiences — all of whom have their own motivations and desires — with experiences they will never forget.

And digital is really good at this. Think of the wonderful way that digital takes advantage of networks — providing connectivity to more and more content via hyperlinking, allowing everyone to pursue ideas and information as far and as deep at they like. Digital also allows for very flexible narrative structure — the same information can appear through multiple channels and interfaces, increasing accessibility to many audiences. Speaking of accessibility, digital enables automatic language translation, screen readers, tabbed navigation, and so much more — all of which help broader audiences find and experience our stories and representations of our collections.

There are so many inspiring colleagues and projects that I worry about making a list for fear of leaving someone out! For me, any colleague who is deeply committed to customer-centered, experiential approaches is an inspiration, so look for projects done by Seb Chan (now at ACMI), Jane Alexander (Cleveland Museum of Art), Adam Lerner (while at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver), and the museums that rely on deep storytelling, like the Tenement Museum, The Field Museum, the 9/11 Memorial, The Holocaust Museum, the Oakland Museum of California, The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam … and I’m leaving out so many great people and places! Also, please read Creating the Visitor-Centered Museum by Samis and Michaelson.

I am curious about this. The International Council of Museum (ICOM) is looking for rethinking and revising the current museum definition. From a digital perspective, what would be your alternative definition?

I like to start at the beginning. We can ask the question: Just what IS a museum? Like all other cultural organizations, museums have mission statements. Those generally boil down to a statement that includes the centrality of the things or ideas that we collect, keep safe, study, preserve and most importantly share with the public. In my view, museums — through the act of sharing our amazing collections — have the potential to be ‘cathedrals of awe’. As such, we can provide jaw-dropping moments of “OMG, that’s amazing!” The kind of experiences that stop people in their tracks, seem to halt time, and resonate somewhere deep within. But you may ask: Who cares about awe? Why would awe be important?

Psychology research has found that people who experience awe in their lives can be redefined by it. They are more connected to others, more generous, more caring. They can actually become better people. Furthermore, we don’t have enough awe in our lives. We get all tied up in being busy. We fret, complain, fall behind, work late, feel like we are running out of time constantly. Without moments of awe we slowly become more individualistic, more self-absorbed, more materialistic, and lonely. Museums have this enormous potential to focus our efforts on connecting people with the stories that engage their sense of awe. In fact, I would argue that — despite its dark potential to isolate and anonymize — digital technology is also capable of delivering real engagement, delight, surprise, emotion, connections to others — and it can open doorways into new experiences.

But we can’t just unlock the vault — people don’t just need more information — that would be like reading the phone book, and no one does that. What we need to be are great storytellers. Our brains light up when we are engaging with narratives. Stories create deeper emotions, along with better brain functioning and memory. At Mia, we take storytelling very seriously. We don’t just push out content and assume all is well. We do formal evaluations to see if it any of this matters. What have we found? In a nutshell, people use digital devices to access stories, and they do it together, sharing and showing what they’ve found with the people around them — often laughing and talking. In addition, the visitors who engage with digital content they spend more time in the museum with the collection and can remember the stories even several weeks after their visit.

From my perspective, the alternate definition of a museum is deeply enmeshed with the experiences our visitors can have with our content, and one high-priority goal is to deliver the sensation of awe — in that regard, museums can actually make our world a better place.

In The Agile Museum (2016), you mention some of the applied lessons from the Minneapolis Institute of Art in relation to new approaches to leadership. Can you highlight some of them for our class of Museum Digital Strategies at Pratt? What does it mean to be innovative in The Agile Museum now at Mia?

To approach this correctly, I’d like to begin by looking at the four Agile values developed about 20 years ago for the practice of software development:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

Now let’s reword these values and apply them to an organizational framework. I recognize that I’m taking a few liberties here, and adding a bit of my own perspective.

- People matter the most. Even if you have the best workplace ever and you have great plans for your business, if you hire and retain the wrong kind of people it will never work. Hone your talent strategy, and develop a workplace culture of mutual respect, positivity, humility and empowerment.

- What you do each day is more important than a steadfast commitment to carefully crafted rules. That doesn’t mean there are no rules at all, it’s just that actions always speak louder than words.

- Working together on shared goals will succeed and provide satisfaction and a sense of accomplishment for everyone. Conversely, a boss barking out orders or forcing people to work in specific ways leads to staff attrition, resistance or even rebellion.

- The core of agility in an organization is the capacity and willingness to honestly assess what’s happening and make any necessary pivot in order to keep engaging your customers. Making plans is fine, but sticking to a failing plan is not. Plans should not be precious, they should simply be starting points.

There are many more aspects of becoming an innovative and agile organization, and I cannot cover them all in this space. I’ve written elsewhere about some of these aspects, here are two examples:

- We need to reconsider how we build the structure of our organizations. In a traditional model, authority flows only from the top and staff are seen as “underlings” in need of careful supervision. In an agile model, everyone has value and will join self-organized teams to accomplish important goals. Authority is distributed so that everyone can make decisions and keep moving forward. For more on how this might be considered, see https://thoughtsparked.blogspot.com/2018/01/organizational-structures-time-for-some.html

- Putting teams together and helping them be successful is a key aspect to an agile organization. For more about high-performing teams, see https://thoughtsparked.blogspot.com/2017/10/group-team-or-ensemble.html

You are also recognized for leadership in the cultural sector. What advice can you give to future digital leaders in the museum field?

Focus on people first — building relationships, listening deeply, being present and engaged. Museums are run by the people who work there, and those people form the backbone of everything that the museum will do, successful or not. Some people call this “soft skills”, but I take real issue with that name and its connotation that people skills are somehow less important. For more on that, see https://thoughtsparked.blogspot.com/2018/12/there-are-no-soft-skills-there-are-only.html

Leadership in the cultural heritage sector can be challenging, but it can also be wonderfully creative. Have a look at this deck for some more of my perspective on why innovative leadership is a great fit for the cultural heritage sector: https://www.slideshare.net/dhegley/innovative-leadership-in-a-museum

Digital leaders are often asked to craft a special digital strategy for their organizations. I believe that there are very important pros and cons to weigh before developing a specific digital strategy, including:

Potential pros

- Aligns digital efforts and enhances institutional buy-in

- Provides clarity & transparency

- Helps ensure relevancy & long-term success of digital

- Recognizes digital as a dynamic, speciality area

- Provides language and perspectives to support funding and partnership opportunities

Potential cons

- Confirms that digital is separate, in a silo, someone else’s job, not core to mission

- Sounds self-justifying (or even defensive)

- Implies that digital is merely a series of projects

For some further perspectives on digital strategy, see:

https://www.slideshare.net/dhegley/aam-2017-digital-strategy-in-action?from_action=save

https://www.slideshare.net/dhegley/practical-approaches-to-digital-strategy-planning-aam-2016

I have been known to advocate for organizations NOT to craft a stand-alone digital strategy, but rather to weave digital and technology into the overall strategy in places where it is applicable and useful. See my blog post A (Somewhat) Tongue in Cheek Digital Strategy Consultation.

The bottom line is that a good digital strategy is part and parcel of the overall organizational strategy, incorporated throughout the organization where it will be effective and helpful, and not considered separate or optional.

Finally, what is your vision for the future of the digital culture at Mia?

I’d rather think more broadly than just Mia. Digital has such potential across our sector, when approached intentionally and strategically. Important considerations in planning for the future of digital technology in any organization include:

- What is the purpose of technology and digital in your organization? Define the “why” first, without regard to specific technologies. That purpose becomes the guiding principle for making good decisions about which technologies to implement and how to allocate resources. Never pursue technology for technology’s sake — never chase shiny new digital devices — always define customer goals, then look for technologies that deliver on those needs.

- What is the reporting structure and leadership model for digital at your museum? Will you represent digital at the highest executive level of the organization, or does it report through a specific channel (such as Marketing, Finance, Operations, etc.)? Be clear on this, including why it makes the most sense for your organization. See https://thoughtsparked.blogspot.com/2017/09/what-and-where-is-digital.html

- What is the budget for technology, including new initiatives and the funds to sustain efforts over time. In brief: Show me your budget, and I’ll tell you exactly what your organization values. In the cultural heritage sector, the total operating budget percentage for digital technology efforts varies widely. In my opinion, if it’s less than 7.5% of the total budget, it is likely to be undervalued and under-resourced, and also likely to be seen as ineffective no matter how hard the staff might work. That percentage is the lowest from which digital can be effective.

- What is the staffing plan for technology? What is the plan for recruiting, hiring and staff retention? Does your organization understand that salaries for skilled technical jobs will seem out-of-ratio to your other similar-level jobs? In other words, are you prepared to pay a software developer more than a curator? Who will lead the staffing efforts, and how?

If I take the answer to this question in another direction, I can also envision what the future of digital might look like in our sector: near-, medium- and longer-term.

- Near-term:

a. Gathering data about our customers (ethically) and then using that information for personalized experiences and targeted marketing efforts that drive participation.

b. Digital storytelling: Museum customers are eager to know more, but our traditional mode of wall label augmented by an audio guide stop is out-moded. Not to mention that most museum visitors come with other people and aim to socialize while onsite, so they find an audio guide to be isolating and unsatisfactory. Digital platforms, used well, give us an opportunity to provide layered and hyperlinked content, so that visitors can dig in as deep as they wish. We’ve found through intensive customer research that we also succeed when we shift the tone and voice of our storytelling, moving from scholarly passive voice to casual first-person voice. A focus on narratives really engages visitors, and digital can provide these very effectively. See https://www.slideshare.net/dhegley/overall-interpretive-framework-v2 https://www.slideshare.net/dhegley/the-dream-the-team-the-results

c. Media production: to support and augment digital storytelling, it’s vital to create engaging multimedia content, including video, audio, and interactive content. We use a cross-functional content development team (curatorial + education + visitor engagement + digital + technology staff) to plan, storyboard, and then craft content.

2. Medium-term:

a. Community voice: we are looking for ways to authentically include alternative points of view as part of the museum’s overall narrative. This will include perspectives from different cultures, often in different languages. It has nothing to do with translating our content; instead, it is elevating community voice to the same level of importance and respect as is the scholarly voice.

b. Data-driven decision-making: we collect information, but now need to improve how we use it to inform or drive decisions. This will include new skill sets on staff (data science, statistics) as well as the software needed to move forward (statistical analytics platforms, data visualization, automated decision trees).

3. Longer-term:

a. Augmented Reality in the museum space: as the hardware becomes lightweight, untethered and widely available, museums will be able to share content through heads-up displays. The challenge, of course, is how we can afford to produce the high-quality content that will make these experiences delightful. However, even if we started by offering only wayfinding and hot spot highlights on a few objects, we’d already be succeeding.

b. Artificial Intelligence for customer experience. See https://medium.com/cognitivebusiness/giving-art-a-voice-with-watson-1c1a235cb63a The concept here is for AI to be well-enough informed as to be capable of helping museum visitors get answers to the questions they have, without a need to seek out an expert (and possibly in languages not available from any onsite expert).

Gloriana Amador Agüero.

Museums and Digital Culture, Pratt Institute

Email: gamado14@pratt.edu

Interview with Douglas Hegley was originally published in Museums and Digital Culture – Pratt Institute on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.